автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Library of the World's Best Literature, Ancient and Modern, Vol. 9

LIBRARY OF THE

WORLD'S BEST LITERATURE

ANCIENT AND MODERN

CHARLES DUDLEY WARNER

EDITOR

HAMILTON WRIGHT MABIE

LUCIA GILBERT RUNKLE

GEORGE HENRY WARNER

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Connoisseur Edition

Vol. IX.

NEW YORK

THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY

Connoisseur Edition

LIMITED TO FIVE HUNDRED COPIES IN HALF RUSSIA

No. ..........

Copyright, 1896, by

R. S. PEALE AND J. A. HILL

All rights reserved

THE ADVISORY COUNCIL

CRAWFORD H. TOY, A. M., LL. D.,

Professor of Hebrew, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

THOMAS R. LOUNSBURY, LL. D., L. H. D.,

Professor of English in the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

WILLIAM M. SLOANE, Ph. D., L. H. D.,

Professor of History and Political Science, Princeton University, Princeton, N. J.

BRANDER MATTHEWS, A. M., LL. B.,

Professor of Literature, Columbia University, New York City.

JAMES B. ANGELL, LL. D.,

President of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.

WILLARD FISKE, A. M., Ph. D.,

Late Professor of the Germanic and Scandinavian Languages and Literatures, Cornell University, Ithaca, N. Y.

EDWARD S. HOLDEN, A. M., LL. D.,

Director of the Lick Observatory, and Astronomer, University of California, Berkeley, Cal.

ALCÉE FORTIER, LIT. D.,

Professor of the Romance Languages, Tulane University, New Orleans, La.

WILLIAM P. TRENT, M. A.,

Dean of the Department of Arts and Sciences, and Professor of English and History, University of the South, Sewanee, Tenn.

PAUL SHOREY, Ph. D.,

Professor of Greek and Latin Literature, University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill.

WILLIAM T. HARRIS, LL. D.,

United States Commissioner of Education, Bureau of Education, Washington, D. C.

MAURICE FRANCIS EGAN, A. M., LL. D.,

Professor of Literature in the Catholic University of America, Washington, D. C.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

VOL. IX

LIVED PAGE Adelbert Von Chamisso1781-1838

3503

The Bargain ('The Wonderful History of Peter Schlemihl') From 'Woman's Love and Life' William Ellery Channing1780-1842

3513

The Passion for Power ('The Life and Character of Napoleon Bonaparte') The Causes of War ('Discourse before the Congregational Ministers of Massachusetts') Spiritual Freedom ('Discourse on Spiritual Freedom') George Chapman1559?-1634

3523

Ulysses and Nausicaa (Translation of Homer's Odyssey) The Duke of Byron is Condemned to Death ('Tragedy of Charles, Duke of Byron') François René Auguste Châteaubriand1768-1848

3531

Christianity Vindicated ('The Genius of Christianity') Description of a Thunder-Storm in the Forest ('Atala') Thomas Chatterton1752-1770

3539

Final Chorus from 'Goddwyn' The Farewell of Sir Charles Baldwin to His Wife ('The Bristowe Tragedie') Mynstrelles Songe An Excelente Balade of Charitie The Resignation Geoffrey Chaucer13—?-1400

3551

BY THOMAS R. LOUNSBURY

Prologue to the 'Canterbury Tales' From the Knight's Tale From the Wife of Bath's Tale From the Pardoner's Tale The Nun's Priest's Tale Truth—Ballade of Good Counsel André Chénier1762-1794

3601

BY KATHARINE HILLARD

The Young Captive Ode Victor Cherbuliez1829-

3609

The Silent Duel ('Samuel Brohl and Company') Samuel Brohl Gives Up the Play (same) Lord Chesterfield1694-1773

3625

From 'Letters to His Son': Concerning Manners; The Control of One's Countenance; Dress as an Index to Character; Some Remarks on Good Breeding The Choice of a Vocation The Literature of China3629

BY ROBERT K. DOUGLAS

Selected Maxims of Morals, Philosophy of Life, Character, Circumstances, etc. (From the Chinese Moralists) Rufus Choate1799-1859

3649

BY ALBERT STICKNEY

The Puritan in Secular and Religious Life (From Address at Ipswich Centennial, 1834) The New-Englander's Character (same) Of the American Bar (From Address before Cambridge Law School) Daniel Webster (From Eulogy at Dartmouth College) St. John Chrysostom347-407

3665

BY JOHN MALONE

That Real Wealth is from Within On Encouragement During Adversity ('Letters to Olympias') Concerning the Statutes (Homily) Marcus Tullius Cicero106-43 B.C.

3675

BY WILLIAM CRANSTON LAWTON

Of the Offices of Literature and Poetry ('Oration for the Poet Archias') Honors Proposed for the Dead Statesman Sulpicius (Ninth Philippic) Old Friends Better than New ('Dialogue on Friendship') Honored Old Age ('Dialogue on Old Age') Death is Welcome to the Old (same) Great Orators and Their Training ('Dialogue on Oratory') Letters: To Tiro; To Atticus Sulpicius Consoles Cicero after His Daughter Tullia's Death Cicero's Reply to Sulpicius A Homesick Exile Cicero's Vacillation in the Civil War Cicero's Correspondents: Cæsar to Cicero; Cæsar to Cicero; Pompey to Cicero; Cælius in Rome to Cicero in Cilicia; Matins to Cicero The Dream of Scipio The Cid1045?-1099

3725

BY CHARLES SPRAGUE SMITH

From 'The Poem of My Cid': Leaving Burgos; Farewell to His Wife at San Pedro de Cardeña; Battle Scene; The Challenges; Conclusion Earl of Clarendon (Edward Hyde)1609-1674

3737

The Character of Lord Falkland Marcus A. H. Clarke1846-1881

3745

How a Penal System can Work ('His Natural Life') The Valley of the Shadow of Death (same) Matthias Claudius1740-1815

3756

Speculations on New-Year's Day (The Wandsbecker Bote) Rhine Wine Winter Night Song Henry Clay1777-1852

3761

BY JOHN R. PROCTER

Public Spirit in Politics (Speech in 1849) On the Greek Struggle for Independence (Speech in 1824) South-American Independence as Related to the United States (Speech in 1818) From the Valedictory to the Senate in 1842 From the Lexington 'Speech on Retirement to Private Life' Cleanthes331-232 B.C.

3784

Hymn to Zeus Samuel Langhorne Clemens (Mark Twain)1835-

3787

The Child of Calamity ('Life on the Mississippi') A Steamboat Landing at a Small Town (same) The High River: and a Phantom Pilot (same) An Enchanting River Scene (same) The Lightning Pilot (same) An Expedition against Ogres ('A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court') The True Prince and the Feigned One ('The Prince and the Pauper') Arthur Hugh Clough1819-1861

3821

BY CHARLES ELIOT NORTON

There is No God The Latest Decalogue To the Unknown God Easter Day—Naples, 1849 It Fortifies My Soul to Know Say Not, The Struggle Naught Availeth Come Back As Ships Becalmed The Unknown Course The Gondola The Poet's Place in Life On Keeping within One's Proper Sphere ('The Bothie of Tober-na-Vuolich') Consider It Again Samuel Taylor Coleridge1772-1834

3843

BY GEORGE E. WOODBERRY

Kubla Khan The Albatross ('The Rime of the Ancient Mariner') Time, Real and Imaginary Dejection: An Ode The Three Treasures To a Gentleman Ode to Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire The Pains of Sleep Song, by Glycine Youth and Age Phantom or Fact William Collins1721-1759

3871

How Sleep the Brave The Passions To Evening Ode on the Death of Thomson William Wilkie Collins1824-1889

3879

The Sleep-Walking ('The Moonstone') Count Fosco ('The Woman in White')FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

VOLUME IX

PAGEThe Koran (Colored plate)

Frontispiece

Geoffrey Chaucer (Portrait)3552

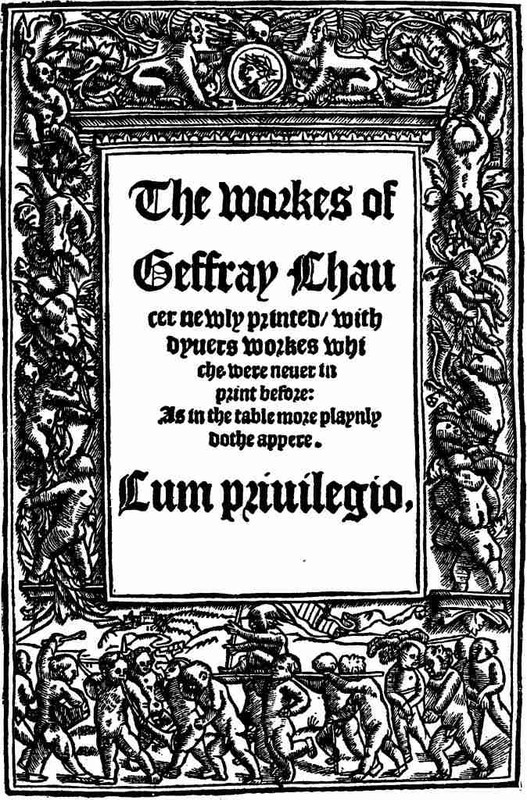

Chaucer, Old Title-Page (Fac-simile)3562

Lord Chesterfield (Portrait)3626

Oldest Chinese Writing (Fac-simile)3630

Cicero (Portrait)3676

"Winter" (Photogravure)3760

Henry Clay (Portrait)3762

Samuel L. Clemens (Portrait)3788

"The Gondola" (Photogravure)3838

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (Portrait)3844

VIGNETTE PORTRAITS

Adelbert von Chamisso

William Ellery Channing

George Chapman

François René Auguste Châteaubriand

Thomas Chatterton

Andre Chénier

Victor Cherbuliez

Rufus Choate

Earl of Clarendon

Matthias Claudius

William Collins

William Wilkie Collins

ADELBERT VON CHAMISSO

(1781-1838)

ouis Charles Adelaide de Chamisso, known as Adelbert von Chamisso, the youngest son of Count Louis Marie de Chamisso, was born in the paternal castle of Boncourt, in Champagne, January 30th, 1781. Driven into exile by the Revolution, the family of loyalists sought refuge in the Low Countries and afterward in Germany, settling in Berlin in 1797. In later years the other members of the family returned to France and established themselves once more as Frenchmen in their native land; but Adelbert von Chamisso, German by nature and characteristics as well as by virtue of his early education and environment, struck root in Germany and was the genuine product of German soil. In 1796 the young Chamisso became page to Queen Louise of Prussia, and while at court, by the Queen's directions, he received the most careful education. He was made ensign in 1798 and lieutenant in 1801, in the Regiment von Goetze. A military career was repugnant to him, and his French antecedents did not tend to make his life agreeable among the German officers. That the service was not wholly without interest, however, is shown by the two treatises upon military subjects written by him in 1798 and 1799.

Chamisso

As a young officer he belonged to a romantic brotherhood calling itself "The Polar Star," which counted among its members his lifelong friend Hitzig, Alexander zur Lippe, Varnhagen, and other young writers of the day. He diligently applied himself to the mastery of the German tongue, made translations of poems and dramas, and to relieve the irksomeness of his military life incessantly studied Homer. His most ambitious literary effort of this time was a 'Faust' (1803), a metaphysical, somewhat sophomoric attempt, but the only one of his early poems that he admitted into his collected works.

While still in the Prussian army, he edited with Varnhagen and Neumann a periodical called the Musenalmanach (1804), which existed three years. After repeated but vain efforts to obtain release from the uncongenial military service, the capitulation of Hameln at length set him free (1806). He left Germany and went to France; but, disappointed in his hopes, unsettled and without plans, he returned, and several years were lost in profitless and desultory wanderings. From 1810 to 1812 he was again in France. Here he became acquainted with Alexander von Humboldt and Uhland, and renewed his friendship with Wilhelm Schlegel. With Helmina von Chézy he undertook the translation into French of Schlegel's Vienna lectures upon art and literature. Chamisso was indifferent to the task, and the translation went on but slowly. To expedite the work he was invited to stay at Chaumont, the residence of Madame de Staël, where Schlegel was a member of her household. Here his careless personal habits and his inevitable pipe brought odium upon him in that polished circle.

Madame de Staël was always his friend, and in 1811 he went to her at Coppet, where by a happy chance he took up the study of botany, with August de Staël as instructor. Filled with enthusiasm for his new pursuit, he made excursions through Switzerland, collecting and botanizing. The period of indecision was at an end, and in 1812, at the age of thirty-one, he matriculated as student of medicine at the University of Berlin, and applied himself with resolution to the study of the natural sciences. During the war against Napoleon he sought refuge in Kunersdorf with the Itzenplitz family, where he occupied his time with botany and the instruction of young Itzenplitz. It was during this time (1813) that 'Peter Schlemihl's Wundersame Geschichte' (Peter Schlemihl's Wonderful History) was written,—one of the masterpieces of German literature. His 'Faust' and 'Fortunatus' had in some degree foreshadowed his later and more famous work,—'Faust' in the compact with the devil, 'Fortunatus' in the possession of the magical wishing-bag. The simple motif of popular superstition, the loss of one's shadow, familiar in folk-stories and already developed by Goethe in his 'Tales,' and by Körner in 'Der Teufel von Salamanca' (The Devil of Salamanca), was treated by Chamisso with admirable simplicity, directness of style, and realism of detail.

Chamisso's divided allegiance to France and Germany made the political situation of the times very trying for him, and it was with joy that he welcomed an appointment as scientist to a Russian polar expedition, fitted out under the direction of Count Romanzoff, and commanded by Captain Kotzebue (1815-1818). The record of the scientific results of this expedition, as published by Kotzebue, was full of misstatements; and to correct these, Chamisso wrote the 'Tagebuch' (Journal) in 1835, a work whose pure and plastic style places it in the first order of books of travel, and entitles its author, in point of description, to rank with Von Humboldt among the best writers of travels of the first half of the century.

After three years of voyaging, Chamisso returned to Berlin, and in 1819 he was made a member of the Society of Natural Sciences and received the degree of Ph.D. from the University of Berlin, was appointed adjunct custodian of the botanical garden in New Schöneberg, and in September of the same year he married Antonie Piaste.

An indemnity granted by France to the French emigrants put him in possession of the sum of one hundred thousand francs, and in 1825 he again visited Paris, where he remained some months among old friends and new interests. The period of his great activity was after this date. His life was now peaceful and domestic. Poetry and botany flourished side by side. Chamisso, to his own astonishment, found himself read and admired, and everywhere his songs were sung. To the influence of his wife we owe the cycles of poems, 'Frauen-Liebe und Leben' (Woman's Love and Life), and 'Lebens Lieder und Bilder' (Life's Songs and Pictures), for without her they would have been impossible. The former cycle inspired Robert Schumann in the first days of his happy married life, and the music of these songs has made 'Woman's Love and Life' familiar to all the world. 'Salas y Gomez,' a reminiscence of his voyage around the world, appeared in the Musenalmanach in 1830. The theme of this poem was the development of the romantic possibilities suggested by the sight of the profound loneliness and grandeur of the South Sea island, Salas y Gomez. Chamisso translated Andersen and Béranger, made translations from the Chinese and Tonga, and his version of the Eddic Song of Thrym ('Das Lied von Thrym') is among the best translations from the Icelandic that have been made.

In 1832 he became associate editor of the Berlin Deutscher Musenalmanach, which position he held until his death, and in his hands the periodical attained a high degree of influence and importance. His health failing, he resigned his position at the Botanical Garden, retiring upon full pay. He died at Berlin, August 21st, 1838.

Frenchman though he was, his entire conception of life and the whole character of his writings are purely German, and show none of the French characteristics of his time. Chamisso, as botanist, traveler, poet, and editor, made important contributions in each and every field, although outside of Germany his fame rests chiefly upon his widely known 'Schlemihl,' which has been translated into all the principal languages of Europe.

THE BARGAIN

From 'The Wonderful History of Peter Schlemihl'

After a fortunate, but for me very troublesome voyage, we finally reached the port. The instant that I touched land in the boat, I loaded myself with my few effects, and passing through the swarming people I entered the first and least house before which I saw a sign hang. I requested a room; the boots measured me with a look, and conducted me into the garret. I caused fresh water to be brought, and made him exactly describe to me where I should find Mr. Thomas John.

"Before the north gate; the first country-house on the right hand; a large new house of red and white marble, with many columns."

"Good." It was still early in the day. I opened at once my bundle; took thence my new black-cloth coat; clad myself cleanly in my best apparel; put my letter of introduction into my pocket, and set out on the way to the man who was to promote my modest expectations.

When I had ascended the long North Street, and reached the gate, I soon saw the pillars glimmer through the foliage. "Here it is, then," thought I. I wiped the dust from my feet with my pocket-handkerchief, put my neckcloth in order, and in God's name rang the bell. The door flew open. In the hall I had an examination to undergo; the porter however permitted me to be announced, and I had the honor to be called into the park, where Mr. John was walking with a select party. I recognized the man at once by the lustre of his corpulent self-complacency. He received me very well,—as a rich man receives a poor devil,—even turned towards me, without turning from the rest of the company, and took the offered letter from my hand. "So, so, from my brother. I have heard nothing from him for a long time. But he is well? There," continued he, addressing the company, without waiting for an answer, and pointing with the letter to a hill, "there I am going to erect the new building." He broke the seal without breaking off the conversation, which turned upon riches.

"He that is not master of a million at least," he observed, "is—pardon me the word—a wretch!"

"Oh, how true!" I exclaimed, with a rush of overflowing feeling.

That pleased him. He smiled at me and said, "Stay here, my good friend; in a while I shall perhaps have time to tell you what I think about this." He pointed to the letter, which he then thrust into his pocket, and turned again to the company. He offered his arm to a young lady; the other gentlemen addressed themselves to other fair ones; each found what suited him: and all proceeded towards the rose-blossomed mount.

I slid into the rear without troubling any one, for no one troubled himself any further about me. The company was excessively lively; there was dalliance and playfulness; trifles were sometimes discussed with an important tone, but oftener important matters with levity; and the wit flew with special gayety over absent friends and their circumstances. I was too strange to understand much of all this; too anxious and introverted to take an interest in such riddles.

We had reached the rosery. The lovely Fanny, who seemed the belle of the day, insisted out of obstinacy in breaking off a blossomed stem herself. She wounded herself on a thorn, and the purple streamed from her tender hand as if from the dark roses. This circumstance put the whole party into a flutter. English plaster was sought for. A quiet, thin, lanky, longish, oldish man who stood near, and whom I had not hitherto remarked, put his hand instantly into the tight breast-pocket of his old gray French taffeta coat; produced thence a little pocket-book, opened it, and presented to the lady with a profound obeisance the required article. She took it without noticing the giver, and without thanks; the wound was bound up and we went forward over the hill, from whose back the company could enjoy the wide prospect over the green labyrinth of the park to the boundless ocean.

The view was in reality vast and splendid. A light point appeared on the horizon between the dark flood and the blue of the heaven. "A telescope here!" cried John; and already, before the servants who appeared at the call were in motion, the gray man, modestly bowing, had thrust his hand into his coat pocket, drawn thence a beautiful Dollond, and handed it to Mr. John. Bringing it immediately to his eye, he informed the company that it was the ship which went out yesterday, and was detained in view of port by contrary winds. The telescope passed from hand to hand, but not again into that of its owner. I however gazed in wonder at the man, and could not conceive how the great machine had come out of the narrow pocket; but this seemed to have struck no one else, and nobody troubled himself any further about the gray man than about myself.

Refreshments were handed round; the choicest fruits of every zone, in the costliest vessels. Mr. John did the honors with an easy grace, and a second time addressed a word to me: "Help yourself; you have not had the like at sea." I bowed, but he did not see it; he was already speaking with some one else.

The company would fain have reclined upon the sward on the slope of the hill, opposite to the outstretched landscape, had they not feared the dampness of the earth. "It were divine," observed one of the party, "had we but a Turkey carpet to spread here." The wish was scarcely expressed when the man in the gray coat had his hand in his pocket, and was busied in drawing thence, with a modest and even humble deportment, a rich Turkey carpet interwoven with gold. The servants received it as a matter of course, and opened it on the required spot. The company, without ceremony, took their places upon it; for myself, I looked again in amazement on the man—at the carpet, which measured about twenty paces long and ten in breadth and rubbed my eyes, not knowing what to think of it, especially as nobody saw anything extraordinary in it.

I would fain have had some explanation regarding the man and have asked who he was, but I knew not to whom to address myself, for I was almost more afraid of the gentlemen's servants than of the served gentlemen. At length I took courage, and stepped up to a young man who appeared to me to be of less consideration than the rest, and who had often stood alone. I begged him softly to tell me who the agreeable man in the gray coat there was.

"He there, who looks like an end of thread that has escaped out of a tailor's needle?"

"Yes, he who stands alone."

"I don't know him," he replied, and—in order to avoid a longer conversation with me, apparently—he turned away and spoke of indifferent matters to another.

The sun began now to shine more powerfully, and to inconvenience the ladies. The lovely Fanny addressed carelessly to the gray man—whom, as far as I am aware, no one had yet spoken to—the trifling question whether he "had not, perchance, also a tent by him?" He answered her by an obeisance most profound, as if an unmerited honor were done him, and had already his hand in his pocket, out of which I saw come canvas, poles, cordage, iron-work,—in short, everything which belongs to the most splendid pleasure-tent. The young gentlemen helped to expand it, and it covered the whole extent of the carpet, and nobody found anything remarkable in it.

I had already become uneasy—nay, horrified—at heart; but how completely so, as at the very next wish expressed I saw him pull out of his pocket three roadsters I tell you, three beautiful great black horses, with saddle and caparison. Take it in, for Heaven's sake!—three saddled horses, out of the same pocket from which already a pocket-book, a telescope, an embroidered carpet twenty paces long and ten broad, a pleasure-tent of equal dimensions and all the requisite poles and irons, had come forth! If I did not protest to you that I saw it myself with my own eyes, you could not possibly believe it.

Embarrassed and obsequious as the man himself appeared to be, little as was the attention which had been bestowed upon him, yet to me his grisly aspect, from which I could not turn my eyes, became so fearful that I could bear it no longer.

I resolved to steal away from the company, which from the insignificant part I played in it seemed to me an easy affair. I proposed to myself to return to the city to try my luck again on the morrow with Mr. John, and if I could muster the necessary courage, to question him about the singular gray man. Had I only had the good fortune to escape so well!

I had already actually succeeded in stealing through the rosery, and on descending the hill found myself on a piece of lawn, when, fearing to be encountered in crossing the grass out of the path, I cast an inquiring glance round me. What was my terror to behold the man in the gray coat behind me, and making towards me! The next moment he took off his hat before me, and bowed so low as no one had ever yet done to me. There was no doubt but that he wished to address me, and without being rude I could not prevent it. I also took off my hat, bowed also, and stood there in the sun with bare head as if rooted to the ground. I stared at him full of terror, and was like a bird which a serpent has fascinated. He himself appeared very much embarrassed. He did not raise his eyes, again bowed repeatedly, drew nearer and addressed me with a soft tremulous voice, almost in a tone of supplication:—

"May I hope, sir, that you will pardon my boldness in venturing in so unusual a manner to approach you? but I would ask a favor. Permit me most condescendingly—"

"But in God's name!" exclaimed I in my trepidation, "what can I do for a man who—" we both started, and as I believe, reddened.

After a moment's silence he again resumed:—

"During the short time that I had the happiness to find myself near you, I have, sir, many times,—allow me to say it to you,—really contemplated with inexpressible admiration the beautiful, beautiful shadow which, as it were with a certain noble disdain and without yourself remarking it, you cast from you in the sunshine. The noble shadow at your feet there! Pardon me the bold supposition, but possibly you might not be indisposed to make this shadow over to me."

I was silent, and a mill-wheel seemed to whirl round in my head. What was I to make of this singular proposition to sell my own shadow? He must be mad, thought I; and with an altered tone which was more assimilated to that of his own humility, I answered him thus:—

"Ha! ha! good friend, have not you then enough of your own shadow? I take this for a business of a very singular sort—"

He hastily interrupted me:—"I have many things in my pocket which, sir, might not appear worthless to you; and for this inestimable shadow I hold the very highest price too small."

It struck cold through me again as I was reminded of the pocket. I knew not how I could have called him good friend. I resumed the conversation, and sought to set all right again by excessive politeness if possible.

"But, sir, pardon your most humble servant; I do not understand your meaning. How indeed could my shadow—"

He interrupted me.

"I beg your permission only here on the spot to be allowed to take up this noble shadow and put it in my pocket; how I shall do that, be my care. On the other hand, as a testimony of my grateful acknowledgment to you, I give you the choice of all the treasures which I carry in my pocket,—the genuine 'spring-root,' the 'mandrake-root,' the 'change-penny,' the 'rob-dollar,' the 'napkin of Roland's page,' a 'mandrake-man,' at your own price. But these probably don't interest you; rather 'Fortunatus's wishing-cap,' newly and stoutly repaired, and a lucky-bag such as he had!"

"The luck-purse of Fortunatus!" I exclaimed, interrupting him; and great as my anxiety was, with that one word he had taken my whole mind captive. A dizziness seized me, and double ducats seemed to glitter before my eyes.

"Honored sir, will you do me the favor to view and to make trial of this purse?" He thrust his hand into his pocket and drew out a tolerably large, well-sewed purse of stout Cordovan leather, with two strong strings, and handed it to me. I plunged my hand into it, and drew out ten gold pieces, and again ten. I extended him eagerly my hand. "Agreed! the business is done: for the purse you have my shadow!"

He closed with me; kneeled instantly down before me, and I beheld him, with an admirable dexterity, gently loosen my shadow from top to toe from the grass, lift it up, roll it together, fold it, and finally pocket it. He arose, made me another obeisance, and retreated towards the rosery. I fancied that I heard him there softly laughing to himself, but I held the purse fast by the strings; all round me lay the clear sunshine, and within me was yet no power of reflection.

At length I came to myself, and hastened to quit the place where I had nothing more to expect. In the first place I filled my pockets with gold; then I secured the strings of the purse fast round my neck, and concealed the purse itself in my bosom. I passed unobserved out of the park, reached the highway and took the road to the city. As, sunk in thought, I approached the gate, I heard a cry behind me:

"Young gentleman! eh! young gentleman! hear you!"

I looked round; an old woman called after me.

"Do take care, sir, you have lost your shadow!"

"Thank you, good mother!" I threw her a gold piece for her well-meant intelligence, and stopped under the trees.

At the city gate I was compelled to hear again from the sentinel, "Where has the gentleman left his shadow?" And immediately again from some women, "Jesus Maria! the poor fellow has no shadow!" That began to irritate me, and I became especially careful not to walk in the sun. This could not, however, be accomplished everywhere; for instance, over the broad street I must next take—actually, as mischief would have it, at the very moment the boys came out of school. A cursed hunchbacked rogue—I see him yet—spied out instantly that I had no shadow. He proclaimed the fact with a loud outcry to the whole assembled literary street youth of the suburb, who began forthwith to criticize me and to pelt me with mud. "Decent people are accustomed to take their shadow with them when they go into the sunshine." To defend myself from them I threw whole handfuls of gold amongst them, and sprang into a hackney coach which some compassionate soul procured for me. As soon as I found myself alone in the rolling carriage, I began to weep bitterly. The presentiment must already have arisen in me that on earth, far as gold transcends merit and virtue in estimation, so much higher than gold itself is the shadow valued; and as I had earlier sacrificed wealth to conscience, I had now thrown away the shadow for mere gold. What in the world could and would become of me!

FROM 'WOMAN'S LOVE AND LIFE'

Thou ring upon my finger, My little golden ring, Against my fond bosom I press thee, And to thee my fond lips cling.

My girlhood's dream was ended, Its peaceful, innocent grace, Forlorn I woke, and so lonely, In desolate infinite space.

Thou ring upon my finger, Thou bringest me peace on earth, And thou my eyes hast opened To womanhood's infinite worth.

I'll love and serve him forever, And live for him alone; I'll give him my life, but to find it Transfigured in his own.

Thou ring upon my finger, My little golden ring, Against my fond bosom I press thee, And to thee my fond lips cling.

Translation of Charles Harvey Genung.

WILLIAM ELLERY CHANNING

(1780-1842)

r. Channing, the recognized leader although not the originator of the Unitarian movement in this country, was a man of singular spirituality, sweetness of disposition, purity of life, and nobility of character. He was thought by some to be austere and cold in temperament, and timid in action; but this was rather a misconception of a life given to conscientious study, and an effort to allow due weight to opposing arguments. He was not liable to be swept from his moorings by momentary enthusiasm. As a writer he was clear and direct, admirably perspicuous in style, without great ornament, much addicted to short and simple sentences, though singularly enough an admirer of those which were long and involved. A critic in Fraser's Magazine wrote of him:—"Channing is unquestionably the first writer of the age. From his writings may be extracted some of the richest poetry and richest conceptions, clothed in language—unfortunately for our literature—too little studied in the day in which we live."

William E. Channing

He was of "blue blood,"—the grandson of William Ellery, one of the signers of the Declaration,—and was born at Newport, Rhode Island, April 7th, 1780. He was graduated at Harvard College with high honors in 1798, and first thought of studying medicine, but was inclined to the direction of the ministry. He became a private tutor in Richmond, Virginia, where he learned to detest slavery. Here he laid the seeds of subsequent physical troubles by imprudent indulgence in asceticism, in a desire to avoid effeminacy. He entered upon the study of theology, which he continued in Cambridge; he was ordained in 1803, and soon became pastor of the Federal Street Church in Boston, in charge of which society he passed his ministerial life. In the following year he was associated with Buckminster and others in the liberal Congregational movement, and this led him into a position of controversy with his orthodox brethren,—one he cordially disliked. But he could not refrain from preaching the doctrines of the dignity of human nature, the supremacy of reason, and religious freedom, of whose truth he was profoundly assured.

It has been truly said that Channing was too much a lover of free thought, and too desirous to hold only what he thought to be true, to allow himself to be bound by any party ties. "I wish," he himself said, "to regard myself as belonging not to a sect but to the community of free minds, of lovers of truth and followers of Christ, both on earth and in heaven. I desire to escape the narrow walls of a particular church, and to stand under the open sky in the broad light, looking far and wide, seeing with my own eyes, hearing with my own ears, and following Truth meekly but resolutely, however arduous or solitary be the path in which she leads."

He was greatly interested in temperance, in the anti-slavery movement, in the elevation of the laboring classes, and other social reforms; and after 1824, when Dr. Gannett became associate pastor, he gave much time to work in these directions. His death occurred at Bennington, Vermont, April 2d, 1842. His literary achievements are mainly or wholly in the line of his work,—sermons, addresses, and essays; but they were prepared with scrupulous care, and have the quality naturally to be expected from a man of broad and catholic spirit, wide interests, and strong love of literature. His works, in six volumes, are issued by the American Unitarian Association, which also publishes a 'Memorial' by his nephew, William Henry Channing, in three volumes.

THE PASSION FOR POWER

From 'The Life and Character of Napoleon Bonaparte'

The passion for ruling, though most completely developed in despotisms, is confined to no forms of government. It is the chief peril of free States, the natural enemy of free institutions. It agitates our own country, and still throws an uncertainty over the great experiment we are making here in behalf of liberty.... It is the distinction of republican institutions, that whilst they compel the passion for power to moderate its pretensions, and to satisfy itself with more limited gratifications, they tend to spread it more widely through the community, and to make it a universal principle. The doors of office being opened to all, crowds burn to rush in. A thousand hands are stretched out to grasp the reins which are denied to none. Perhaps in this boasted and boasting land of liberty, not a few, if called to state the chief good of a republic, would place it in this: that every man is eligible to every office, and that the highest places of power and trust are prizes for universal competition. The superiority attributed by many to our institutions is, not that they secure the greatest freedom, but give every man a chance of ruling; not that they reduce the power of government within the narrowest limits which the safety of the State admits, but throw it into as many hands as possible. The despot's great crime is thought to be that he keeps the delight of dominion to himself, that he makes a monopoly of it; whilst our more generous institutions, by breaking it into parcels and inviting the multitude to scramble for it, spread this joy more widely. The result is that political ambition infects our country and generates a feverish restlessness and discontent, which to the monarchist may seem more than a balance for our forms of liberty. The spirit of intrigue, which in absolute governments is confined to courts, walks abroad through the land; and as individuals can accomplish no political purposes single-handed, they band themselves into parties, ostensibly framed for public ends, but aiming only at the acquisition of power. The nominal sovereign,—that is, the people,—like all other sovereigns, is courted and flattered and told that it can do no wrong. Its pride is pampered, its passions inflamed, its prejudices made inveterate. Such are the processes by which other republics have been subverted, and he must be blind who cannot trace them among ourselves. We mean not to exaggerate our dangers. We rejoice to know that the improvements of society oppose many checks to the love of power. But every wise man who sees its workings must dread it as one chief foe.

This passion derives strength and vehemence in our country from the common idea that political power is the highest prize which society has to offer. We know not a more general delusion, nor is it the least dangerous. Instilled as it is in our youth, it gives infinite excitement to political ambition. It turns the active talents of the country to public station as the supreme good, and makes it restless, intriguing, and unprincipled. It calls out hosts of selfish competitors for comparatively few places, and encourages a bold, unblushing pursuit of personal elevation, which a just moral sense and self-respect in the community would frown upon and cover with shame.

THE CAUSES OF WAR

From a 'Discourse delivered before the Congregational ministers of Massachusetts'

One of the great springs of war may be found in a very strong and general propensity of human nature—in the love of excitement, of emotion, of strong interest; a propensity which gives a charm to those bold and hazardous enterprises which call forth all the energies of our nature. No state of mind, not even positive suffering, is more painful than the want of interesting objects. The vacant soul preys on itself, and often rushes with impatience from the security which demands no effort, to the brink of peril. This part of human nature is seen in the kind of pleasures which have always been preferred. Why has the first rank among sports been given to the chase? Because its difficulties, hardships, hazards, tumults, awaken the mind, and give to it a new consciousness of existence, and a deep feeling of its powers. What is the charm which attaches the statesman to an office which almost weighs him down with labor and an appalling responsibility? He finds much of his compensation in the powerful emotion and interest awakened by the very hardships of his lot, by conflict with vigorous minds, by the opposition of rivals, by the alternations of success and defeat. What hurries to the gaming tables the man of prosperous fortune and ample resources? The dread of apathy, the love of strong feeling and of mental agitation. A deeper interest is felt in hazarding than in securing wealth, and the temptation is irresistible.... Another powerful principle of our nature which is the spring of war, is the passion for superiority, for triumph, for power. The human mind is aspiring, impatient of inferiority, and eager for control. I need not enlarge on the predominance of this passion in rulers, whose love of power is influenced by its possession, and who are ever restless to extend their sway. It is more important to observe that were this desire restrained to the breasts of rulers, war would move with a sluggish pace. But the passion for power and superiority is universal; and as every individual, from his intimate union with the community, is accustomed to appropriate its triumphs to himself, there is a general promptness to engage in any contest by which the community may obtain an ascendency over other nations. The desire that our country should surpass all others would not be criminal, did we understand in what respects it is most honorable for a nation to excel; did we feel that the glory of a State consists in intellectual and moral superiority, in pre-eminence of knowledge, freedom and purity. But to the mass of the people this form of pre-eminence is too refined and unsubstantial. There is another kind of triumph which they better understand: the triumph of physical power, triumph in battle, triumph not over the minds but the territory of another State. Here is a palpable, visible superiority; and for this a people are willing to submit to severe privations. A victory blots out the memory of their sufferings, and in boasting of their extended power they find a compensation for many woes.... Another powerful spring of war is the admiration of the brilliant qualities displayed in war. Many delight in war, not for its carnage and woes, but for its valor and apparent magnanimity, for the self-command of the hero, the fortitude which despises suffering, the resolution which courts danger, the superiority of the mind to the body, to sensation, to fear. Men seldom delight in war, considered merely as a source of misery. When they hear of battles, the picture which rises to their view is not what it should be—a picture of extreme wretchedness, of the wounded, the mangled, the slain; these horrors are hidden under the splendor of those mighty energies which break forth amidst the perils of conflict, and which human nature contemplates with an intense and heart-thrilling delight. Whilst the peaceful sovereign who scatters blessings with the silence and constancy of Providence is received with a faint applause, men assemble in crowds to hail the conqueror,—perhaps a monster in human form, whose private life is blackened with lust and crime, and whose greatness is built on perfidy and usurpation. Thus war is the surest and speediest way to renown; and war will never cease while the field of battle is the field of glory, and the most luxuriant laurels grow from a root nourished with blood.

SPIRITUAL FREEDOM

From the 'Discourse on Spiritual Freedom,' 1830

I consider the freedom or moral strength of the individual mind as the supreme good, and the highest end of government. I am aware that other views are often taken. It is said that government is intended for the public, for the community, not for the individual. The idea of a national interest prevails in the minds of statesmen, and to this it is thought that the individual may be sacrificed. But I would maintain that the individual is not made for the State so much as the State for the individual. A man is not created for political relations as his highest end, but for indefinite spiritual progress, and is placed in political relations as the means of his progress. The human soul is greater, more sacred than the State, and must never be sacrificed to it. The human soul is to outlive all earthly institutions. The distinction of nations is to pass away. Thrones which have stood for ages are to meet the doom pronounced upon all man's works. But the individual mind survives, and the obscurest subject, if true to God, will rise to power never wielded by earthly potentates.

A human being is a member of the community, not as a limb is a member of the body, or as a wheel is a part of a machine, intended only to contribute to some general joint result. He was created not to be merged in the whole, as a drop in the ocean or as a particle of sand on the seashore, and to aid only in composing a mass. He is an ultimate being, made for his own perfection as his highest end; made to maintain an individual existence, and to serve others only as far as consists with his own virtue and progress. Hitherto governments have tended greatly to obscure this importance of the individual, to depress him in his own eyes, to give him the idea of an outward interest more important than the invisible soul, and of an outward authority more sacred than the voice of God in his own secret conscience. Rulers have called the private man the property of the State, meaning generally by the State themselves; and thus the many have been immolated to the few, and have even believed that this was their highest destination. These views cannot be too earnestly withstood. Nothing seems to me so needful as to give to the mind the consciousness, which governments have done so much to suppress, of its own separate worth. Let the individual feel that through his immortality he may concentrate in his own being a greater good than that of nations. Let him feel that he is placed in the community, not to part with his individuality or to become a tool, but that he should find a sphere for his various powers, and a preparation for immortal glory. To me the progress of society consists in nothing more than in bringing out the individual, in giving him a consciousness of his own being, and in quickening him to strengthen and elevate his own mind.

In thus maintaining that the individual is the end of social institutions, I may be thought to discourage public efforts and the sacrifice of private interests to the State. Far from it. No man, I affirm, will serve his fellow-beings so effectually, so fervently, as he who is not their slave; as he who, casting off every other yoke, subjects himself to the law of duty in his own mind. For this law enjoins a disinterested and generous spirit, as man's glory and likeness to his Maker. Individuality, or moral self-subsistence, is the surest foundation of an all-comprehending love. No man so multiplies his bonds with the community, as he who watches most jealously over his own perfection. There is a beautiful harmony between the good of the State and the moral freedom and dignity of the individual. Were it not so, were these interests in any case discordant, were an individual ever called to serve his country by acts debasing his own mind, he ought not to waver a moment as to the good which he should prefer. Property, life, he should joyfully surrender to the State. But his soul he must never stain or enslave. From poverty, pain, the rack, the gibbet, he should not recoil; but for no good of others ought he to part with self-control, or violate the inward law. We speak of the patriot as sacrificing himself to the public weal. Do we mean that he sacrifices what is most properly himself, the principle of piety and virtue? Do we not feel that however great may be the good which through his sufferings accrues to the State, a greater and purer glory redounds to himself; and that the most precious fruit of his disinterested services is the strength of resolution and philanthropy which is accumulated in his own soul?...

The advantages of civilization have their peril. In such a state of society, opinion and law impose salutary restraint, and produce general order and security. But the power of opinion grows into a despotism, which more than all things represses original and free thought, subverts individuality of character, reduces the community to a spiritless monotony, and chills the love of perfection. Religion, considered simply as the principle which balances the power of human opinion, which takes man out of the grasp of custom and fashion, and teaches him to refer himself to a higher tribunal, is an infinite aid to moral strength and elevation.

An important benefit of civilization, of which we hear much from the political economist, is the division of labor, by which arts are perfected. But this, by confining the mind to an unceasing round of petty operations, tends to break it into littleness. We possess improved fabrics, but deteriorated men. Another advantage of civilization is, that manners are refined and accomplishments multiplied; but these are continually seen to supplant simplicity of character, strength of feeling, the love of nature, the love of inward beauty and glory. Under outward courtesy we see a cold selfishness, a spirit of calculation, and little energy of love.

I confess I look round on civilized society with many fears, and with more and more earnest desire that a regenerating spirit from heaven, from religion, may descend upon and pervade it. I particularly fear that various causes are acting powerfully among ourselves, to inflame and madden that enslaving and degrading principle, the passion for property. For example, the absence of hereditary distinctions in our country gives prominence to the distinction of wealth, and holds up this as the chief prize to ambition. Add to this the epicurean, self-indulgent habits which our prosperity has multiplied, and which crave insatiably for enlarging wealth as the only means of gratification. This peril is increased by the spirit of our times, which is a spirit of commerce, industry, internal improvements, mechanical invention, political economy, and peace. Think not that I would disparage commerce, mechanical skill, and especially pacific connections among States. But there is danger that these blessings may by perversion issue in a slavish love of lucre. It seems to me that some of the objects which once moved men most powerfully are gradually losing their sway, and thus the mind is left more open to the excitement of wealth. For example, military distinction is taking the inferior place which it deserves: and the consequence will be that the energy and ambition which have been exhausted in war will seek new directions; and happy shall we be if they do not flow into the channel of gain. So I think that political eminence is to be less and less coveted; and there is danger that the energies absorbed by it will be spent in seeking another kind of dominion, the dominion of property. And if such be the result, what shall we gain by what is called the progress of society? What shall we gain by national peace, if men, instead of meeting on the field of battle, wage with one another the more inglorious strife of dishonest and rapacious traffic? What shall we gain by the waning of political ambition, if the intrigues of the exchange take place of those of the cabinet, and private pomp and luxury be substituted for the splendor of public life? I am no foe to civilization. I rejoice in its progress. But I mean to say that without a pure religion to modify its tendencies, to inspire and refine it, we shall be corrupted, not ennobled by it. It is the excellence of the religious principle, that it aids and carries forward civilization, extends science and arts, multiplies the conveniences and ornaments of life, and at the same time spoils them of their enslaving power, and even converts them into means and ministers of that spiritual freedom which when left to themselves they endanger and destroy.

In order, however, that religion should yield its full and best fruit, one thing is necessary; and the times require that I should state it with great distinctness. It is necessary that religion should be held and professed in a liberal spirit. Just as far as it assumes an intolerant, exclusive, sectarian form, it subverts instead of strengthening the soul's freedom, and becomes the heaviest and most galling yoke which is laid on the intellect and conscience. Religion must be viewed, not as a monopoly of priests, ministers, or sects, not as conferring on any man a right to dictate to his fellow-beings, not as an instrument by which the few may awe the many, not as bestowing on one a prerogative which is not enjoyed by all; but as the property of every human being and as the great subject for every human mind. It must be regarded as the revelation of a common Father to whom all have equal access, who invites all to the like immediate communion, who has no favorites, who has appointed no infallible expounders of his will, who opens his works and word to every eye, and calls upon all to read for themselves, and to follow fearlessly the best convictions of their own understandings. Let religion be seized on by individuals or sects, as their special province; let them clothe themselves with God's prerogative of judgment; let them succeed in enforcing their creed by penalties of law, or penalties of opinion; let them succeed in fixing a brand on virtuous men whose only crime is free investigation—and religion becomes the most blighting tyranny which can establish itself over the mind. You have all heard of the outward evils which religion, when thus turned into tyranny, has inflicted; how it has dug dreary dungeons, kindled fires for the martyr, and invented instruments of exquisite torture. But to me all this is less fearful than its influence over the mind. When I see the superstitions which it has fastened on the conscience, the spiritual terrors with which it has haunted and subdued the ignorant and susceptible, the dark appalling views of God which it has spread far and wide, the dread of inquiry which it has struck into superior understandings, and the servility of spirit which it has made to pass for piety—when I see all this, the fire, the scaffold, and the outward inquisition, terrible as they are, seem to me inferior evils. I look with a solemn joy on the heroic spirits who have met, freely and fearlessly, pain and death in the cause of truth and human rights. But there are other victims of intolerance on whom I look with unmixed sorrow. They are those who, spell-bound by early prejudice or by intimidations from the pulpit and the press, dare not think; who anxiously stifle every doubt or misgiving in regard to their opinions, as if to doubt were a crime; who shrink from the seekers after truth as from infection; who deny all virtue which does not wear the livery of their own sect; who, surrendering to others their best powers, receive unresistingly a teaching which wars against reason and conscience; and who think it a merit to impose on such as live within their influence, the grievous bondage which they bear themselves. How much to be deplored is it, that religion, the very principle which is designed to raise men above the judgment and power of man, should become the chief instrument of usurpation over the soul!

GEORGE CHAPMAN

(1559?-1634)

eorge Chapman, the translator of Homer, is of all the Elizabethan dramatists the most undramatic. He is akin to Marlowe in being more of an epic poet than a playwright; but unlike his young compeer "of the mighty line," who in his successive plays learnt how to subdue an essentially epic genius to the demands of the stage, Chapman never got near the true secret of dramatic composition. Yet he witnessed the growth of the glorious Elizabethan drama, from its feeble beginning in 'Gorbodue' and 'Gammer Gurton's Needle' through its very flowering in the immortal masterpieces. He was born about 1559, five years before Marlowe, the "morning star" of the English drama, and he died in 1634, surviving Shakespeare, in whom it reached its maturity, and Beaumont, Middleton, and Fletcher, whose works foreshadow decay. From his native town Hitchin he passed on to Oxford, where he distinguished himself as a classical scholar. Then for sixteen years nothing definite is known about him. His life has been called one of the great blanks of English literature. He is sometimes sent traveling on the Continent, as a convenient means of accounting for this gap, and also to explain the intimate acquaintance with German manners and customs and the language displayed in his tragedy 'Alphonsus, Emperor of Germany,' which argues at least for a trip to that country. In 1594 he published the two hymns in the 'Shadow of Night'; and soon after he must have begun writing for the stage, for his first extant comedy, 'The Blind Beggar of Alexandria,' was acted in 1596, and two years later he appears in Francis Meres's famous enumeration of the poets and wits of the time. Hereafter his life is to be dated by his publications.

George Chapman

He occupies a position unique among the Elizabethans, because of his wide culture and the diverse character of his work. Though held together by his strong personality, it yet can be divided into the distinct groups of comedies, tragedies, poems, and translations. The first of these is the weakest, for Chapman was not a comic genius. 'The Blind Beggar of Alexandria' and 'An Humorous Day's Mirth' deserve but a passing mention. In 1605 'All Fooles' was published, acted six years earlier under the name 'The World Runs on Wheels.' It is a realistic satire, with some good scenes and character-drawing. 'The Gentleman Usher' is full of poetry and ingenious situations. 'Monsieur D'Oline' contains also some good comedy work. 'The Widow's Tears' tells the well-known story of the Ephesian matron; though coarse, it is handled not without comic talent. In his comedy work Chapman is neither new nor original; he followed in Jonson's footsteps, and suggests moreover Terence, Plautus, Fletcher, and Lyly. He has wit, satire, and sarcasm; but along with these, poor construction and little invention. He was going against his grain, and we have here the frankest expression of "pot-boiling" to be found among the Elizabethan dramatists. Writing for the stage was the only kind of literature that really paid; the playhouse was to the Elizabethan what the paper-covered novel is to a modern reader. This accounts for the enormous dramatic productivity of the time, and also explains why the most finely endowed minds, in need of money, produced dramas instead of other imaginative work. By the time he wrote his comedies, Chapman had already won his place as poet and translator, but it earned him no income. Pope, one hundred and twenty-five years later, made a fortune by his translation of Homer. But then the number of readers had increased, and publishers could afford to give large sums to a popular author. Chapman takes rank among the dramatists mainly by his four chief tragedies: 'Bussy d'Ambois,' 'The Revenge of Bussy d'Ambois,' 'The Conspiracy of Charles, Duke of Byron,' and 'The Tragedy of Charles, Duke of Byron.' They are unique among the plays of the period, in that they deal with almost contemporary events in French history; not with the purpose of exciting any feeling for or against the parties introduced, but in calm ignoring of public opinion, they bring recent happenings on the stage to suit the dramatist's purpose. He drew his material mainly from the 'Historiæ Sui Temporis' of Jacques Auguste de Thou, but he troubled himself little about following it with accuracy, or even painting the characters of the chief actors as true to life. In these tragedies, more than in the comedies, we get sight of Chapman the man; indeed, it is his great failing as playwright that his own individuality is constantly cropping out. He alone, of all the great Elizabethan dramatists, was unable to go outside of himself and enter into the habits and thoughts of his characters. Chapman was too much of a scholar and a thinker to be a successful delineator of men. His is the drama of the man who thinks about life, not of one who lives it in its fullness. He does not get into the hearts of men. He has too many theories. Homer had become the ruling influence in his life, and he looked at things from the Homeric point of view and presented life epically. He is at his best in single didactic or narrative passages, and exquisite bits of poetry are prodigally scattered up and down the pages of his tragedies. Next to Shakespeare he is the most sententious of dramatists. He sounded the depths of things in thought which theretofore only Marlowe had done. He is the most metaphysical of dramatists.

Yet his thought is sometimes too much for him, and he becomes obscure. He packs words as tight as Browning, and the sense is often more difficult to unravel. He is best in the closet drama. 'Cæsar and Pompey,' published in 1631 but never acted, contains some of his finest thoughts.

Chapman also collaborated with other dramatists. 'Eastward Ho,' in 1605, written with Marston and Jonson, is one of the liveliest and best constructed Elizabethan comedies, combining the excellences of the three men without their faults. Some allusion to the Scottish nation offended King James; the authors were confined in Fleet Prison and barely escaped having their ears and noses slit. With Shirley he wrote the comedy 'The Ball' and the tragedy 'Chabot, Admiral of France.'

Chapman wrote comedies to make money, and tragedies because it was the fashion of the day, and he studded these latter with exquisite passages because he was a poet born. But he was above all a scholar with wide and deep learning, not only of the classics but also of the Renaissance literature. From 1613 to 1631 he does not appear to have written for the stage, but was occupied with his translations of Homer, Hesiod, Juvenal, Musæus, Petrarch, and others. In 1614, at the marriage of the Princess Elizabeth, was performed in the most lavish manner the 'Memorable Masque of the two Honorable Houses or Inns of Court; the Middle Temple and Lyncoln Inne.' Chapman also completed Marlowe's unfinished 'Hero and Leander.'

His fame however rests on his version of Homer. The first portion appeared in 1598: 'Seven Bookes of the Iliade of Homer, Prince of Poets; Translated according to the Greeke in judgment of his best Commentaries.' In 1611 the Iliad complete appeared, and in 1615 the whole of the Odyssey; though he by no means reproduces Homer faithfully, he approaches nearest to the original in spirit and grandeur. It is a typical product of the English Renaissance, full of vigor and passion, but also of conceit and fancifulness. It lacks the simplicity and the serenity of the Greek, but has caught its nobleness and rapidity. As has been said, "It is what Homer might have written before he came to years of discretion." Yet with all its shortcomings it remains one of the classics of Elizabethan literature. Pope consulted it diligently, and has been accused of at times re-versifying this instead of the Greek. Coleridge said of it:—

"The Iliad is fine, but less equal in the translation [than the Odyssey], as well as less interesting in itself. What is stupidly said of Shakespeare is really true and appropriate of Chapman: 'Mighty faults counterpoised by mighty beauties.' ... It is as truly an original poem as the 'Faerie Queen';—it will give you small idea of Homer, though a far truer one than Pope's epigrams, or Cowper's cumbersome, most anti-Homeric Miltonisms. For Chapman writes and feels as a poet,—as Homer might have written had he lived in England in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. In short, it is an exquisite poem in spite of its frequent and perverse quaintnesses and awkwardness, which are however amply repaid by almost unexampled sweetness and beauty of language, all over spirit and feeling."

Keats's tribute, the sonnet 'On First Looking into Chapman's Homer,' attests another poet's appreciation of the Elizabethan's paraphrase. Keats diligently explored this "new planet" that swam into his ken, and his own poetical diction is at times touched by the quaintness and fancifulness of the elder poet he admired.

Lamb, that most sympathetic critic of the old dramatists, speaks of him as follows:—

"Webster has happily characterized the 'full and heightened' style of Chapman, who of all the English play-writers perhaps approaches nearest to Shakespeare in the descriptive and didactic, in passages which are less purely dramatic. He could not go out of himself, as Shakespeare could shift at pleasure, to inform and animate other existences, but in himself he had an eye to perceive and a soul to embrace all forms and modes of being. He would have made a great epic poet, if indeed he has not abundantly shown himself to be one; for his 'Homer' is not so properly a translation as the stories of Achilles and Ulysses rewritten. The earnestness and passion which he has put into every part of these poems would be incredible to a reader of more modern translations.... The great obstacle to Chapman's translations being read is their unconquerable quaintness. He pours out in the same breath the most just and natural, and the most violent and crude expressions. He seems to grasp at whatever words come first to hand while the enthusiasm is upon him, as if all others must be inadequate to the divine meaning. But passion (the all-in-all in poetry) is everywhere present, raising the low, dignifying the mean, and putting sense into the absurd. He makes his readers glow, weep, tremble, take any affection which he pleases, be moved by words, or in spite of them be disgusted and overcome their disgust."

ULYSSES AND NAUSICAA

From the Translation of Homer's Odyssey

Straight rose the lovely Morn, that up did raise Fair-veil'd Nausicaa, whose dream her praise To admiration took; who no time spent To give the rapture of her vision vent To her loved parents, whom she found within. Her mother set at fire, who had to spin A rock, whose tincture with sea-purple shined; Her maids about her. But she chanced to find Her father going abroad, to council call'd By his grave Senate; and to him exhaled Her smother'd bosom was:—"Loved sire," said she, "Will you not now command a coach for me, Stately and complete? fit for me to bear To wash at flood the weeds I cannot wear Before re-purified? Yourself it fits To wear fair weeds, as every man that sits In place of council. And five sons you have, Two wed, three bachelors, that must be brave In every day's shift, that they may go dance; For these three last with these things must advance Their states in marriage; and who else but I, Their sister, should their dancing rites supply?" This general cause she shew'd, and would not name Her mind of nuptials to her sire, for shame. He understood her yet, and thus replied:— "Daughter! nor these, nor any grace beside, I either will deny thee, or defer, Mules, nor a coach, of state and circular, Fitting at all parts. Go; my servants shall Serve thy desires, and thy command in all." The servants then commanded soon obey'd, Fetch'd coach, and mules join'd in it. Then the Maid Brought from the chamber her rich weeds, and laid All up in coach; in which her mother placed A maund of victuals, varied well in taste, And other junkets. Wine she likewise fill'd Within a goat-skin bottle, and distill'd Sweet and moist oil into a golden cruse, Both for her daughter's and her handmaid's use, To soften their bright bodies, when they rose Cleansed from their cold baths. Up to coach then goes Th' observed Maid; takes both the scourge and reins; And to her side her handmaid straight attains. Nor these alone, but other virgins, graced The nuptial chariot. The whole bevy placed, Nausicaa scourged to make the coach-mules run, That neigh'd, and paced their usual speed, and soon Both maids and weeds brought to the river-side, Where baths for all the year their use supplied. Whose waters were so pure they would not stain, But still ran fair forth; and did more remain Apt to purge stains, for that purged stain within, Which by the water's pure store was not seen. These, here arrived, the mules uncoach'd, and drave Up the gulfy river's shore, that gave Sweet grass to them. The maids from coach then took Their clothes, and steep'd them in the sable brook; Then put them into springs, and trod them clean With cleanly feet; adventuring wagers then, Who should have soonest and most cleanly done. When having thoroughly cleansed, they spread them on The flood's shore, all in order. And then, where The waves the pebbles wash'd, and ground was clear, They bathed themselves, and all with glittering oil Smooth'd their white skins; refreshing then their toil With pleasant dinner, by the river's side. Yet still watch'd when the sun their clothes had dried. Till which time, having dined, Nausicaa With other virgins did at stool-ball play, Their shoulder-reaching head-tires laying by. Nausicaa, with the wrists of ivory, The liking stroke strook, singing first a song, As custom order'd, and amidst the throng Made such a shew, and so past all was seen, As when the chaste-born, arrow-loving Queen, Along the mountains gliding, either over Spartan Taygetus, whose tops far discover, Or Eurymanthus, in the wild boar's chace, Or swift-hooved hart, and with her Jove's fair race, The field Nymphs, sporting; amongst whom, to see How far Diana had priority (Though all were fair) for fairness; yet of all, (As both by head and forehead being more tall) Latona triumph'd, since the dullest sight Might easily judge whom her pains brought to light; Nausicaa so, whom never husband tamed, Above them all in all the beauties flamed. But when they now made homewards, and array'd, Ordering their weeds; disorder'd as they play'd, Mules and coach ready, then Minerva thought What means to wake Ulysses might be wrought, That he might see this lovely-sighted maid, Whom she intended should become his aid, Bring him to town, and his return advance. Her mean was this, though thought a stool-ball chance: The queen now, for the upstroke, strook the ball Quite wide off th' other maids, and made it fall Amidst the whirlpools. At which outshriek'd all, And with the shriek did wise Ulysses wake; Who, sitting up, was doubtful who should make That sudden outcry, and in mind thus strived:— "On what a people am I now arrived? At civil hospitable men, that fear The gods? or dwell injurious mortals here, Unjust and churlish? Like the female cry Of youth it sounds. What are they? Nymphs bred high On tops of hills, or in the founts of floods, In herby marshes, or in leavy woods? Or are they high-spoke men I now am near? I'll prove and see." With this the wary peer Crept forth the thicket, and an olive bough Broke with his broad hand; which he did bestow In covert of his nakedness, and then Put hasty head out. Look how from his den A mountain lion looks, that, all embrued With drops of trees, and weatherbeaten-hued, Bold of his strength goes on, and in his eye A burning furnace glows, all bent to prey On sheep, or oxen, or the upland hart, His belly charging him, and he must part Stakes with the herdsman in his beasts' attempt, Even where from rape their strengths are most exempt: So wet, so weather-beat, so stung with need, Even to the home-fields of the country's breed Ulysses was to force forth his access, Though merely naked; and his sight did press The eyes of soft-haired virgins. Horrid was His rough appearance to them; the hard pass He had at sea stuck by him. All in flight The virgins scattered, frighted with this sight, About the prominent windings of the flood. All but Nausicaa fled; but she fast stood: Pallas had put a boldness in her breast, And in her fair limbs tender fear comprest. And still she stood him, as resolved to know What man he was; or out of what should grow His strange repair to them.

THE DUKE OF BYRON IS CONDEMNED TO DEATH

From the 'Tragedy of Charles, Duke of Byron'

By horror of death, let me alone in peace, And leave my soul to me, whom it concerns; You have no charge of it; I feel her free: How she doth rouse, and like a falcon stretch Her silver wings; a threatening death with death; At whom I joyfully will cast her off. I know this body but a sink of folly, The groundwork and raised frame of woe and frailty; The bond and bundle of corruption; A quick corse, only sensible of grief, A walking sepulchre, or household thief: A glass of air, broken with less than breath, A slave bound face to face to death, till death. And what said all you more? I know, besides, That life is but a dark and stormy night Of senseless dreams, terrors, and broken sleeps; A tyranny, devising pains to plague And make man long in dying, racks his death; And death is nothing: what can you say more? I bring a long globe and a little earth, Am seated like earth, betwixt both the heavens, That if I rise, to heaven I rise; if fall, I likewise fall to heaven; what stronger faith Hath any of your souls? what say you more? Why lose I time in these things? Talk of knowledge, It serves for inward use. I will not die Like to a clergyman; but like the captain That prayed on horseback, and with sword in hand, Threatened the sun, commanding it to stand; These are but ropes of sand.

FRANÇOIS RENÉ AUGUSTE CHÂTEAUBRIAND

(1768-1848)

iscount de Châteaubriand, the founder of the romantic school in French literature, and one of the most brilliant and polished writers of the first half of the nineteenth century, was born at St. Malo in Brittany, September 14th, 1768. On the paternal side he was a direct descendant of Thierri, grandson of Alain III., who was king of Armorica in the ninth century. Destined for the Church, he became a pronounced skeptic, and entered the army. In his nineteenth year he was presented at court, and became acquainted with men of letters like La Harpe, Le Brun, and Fontanes. At the outbreak of the Revolution he quitted the service, and embarked for America in January, 1791. Tiring of the restraints of civilization, civilization, he plunged into the virgin forests of Canada, and for several months lived with the savages. This remarkable experience inspired his most notable romantic work.

Châteaubriand

Returning to France in 1792, he cast his lot with the Royalists, was wounded at Thionville, and finally retired to England, where for eight years he earned a bare support by teaching and translating. His first book was the 'Essay on Revolutions' (1797), which displayed some imagination, little reflection, and an affectation of misanthropy and skepticism. The subsequent change in his convictions followed on the death of his pious mother in 1798. Returning to France he published 'Atala,' an idyll á la mode, founded on the loves of two young savages. Teeming with glowing descriptions of nature, and marked by elevation of sentiment combined with a sensuousness almost Oriental, this barbaric 'Paul and Virginia' immediately established the author's fame. Thus encouraged, in the following year he gave the world his 'Genius of Christianity,' in which the poetic and symbolic features of Christianity are painted in dazzling colors and with great charm of style. The enormous success of this book during the first decade of the century unquestionably did more to revive French interest in religion than the establishment of the Concordat itself. Napoleon testified his gratitude by appointing the author secretary to the embassy at Rome, and afterward minister plenipotentiary to the Valais. When the Duke d'Enghien was assassinated (March 21st, 1804), Châteaubriand resigned from the diplomatic service, although the ink was scarcely dry in which the First Consul had signed his new commission. Two years later the successful author departed on a sentimental pilgrimage to the Holy Land. He visited Asia Minor, Egypt, and Spain, where amid the ruins of the Alhambra he wrote 'The Last of the Abencerrages.' To this interesting tour the world owes the 'Itinerary from Paris to Jerusalem' (1811), that book which in Saintsbury's opinion remains "the pattern of all the picturesque travels of modern times."

With the publication of the 'Itinerary' the literary career of Châteaubriand virtually closes. On the return of the Bourbons to power, the man of letters was tempted to enter the exciting arena of politics, becoming successively ambassador at Berlin, at the court of St. James, delegate to the Congress of Verona, and Minister of Foreign Affairs. In 1830, unwilling to pledge himself to Louis Philippe, he relinquished the dignity of peer of the realm accorded him in 1815, and retired to a life of comparative poverty, which was brightened by the friendship and devotion of Madame Récamier. Until his death on the 4th of July, 1848, Châteaubriand devoted himself to the completion of his 'Mémoires d'Outre-Tombe,' an auto-biographical work which was published posthumously, and which, although diffuse and even puerile at times, contains much brilliant writing.

His contemporaries pronounced Châteaubriand the foremost man of letters of France, if not of all Europe. During the last half of this century his fame has sensibly diminished both at home and abroad, and in the history of French literature he is chiefly significant as marking the transition from the old classical to the modern romantic school. Yet while admitting the glaring faults, exaggerations, affectations, and egotism of the author of the 'Genius of Christianity,' a fair criticism admits his best passages to be unsurpassed for perfection of style and gorgeousness of coloring. 'Atala' is a classic with real life in it even yet,—powerful, interesting, and even thrilling, in spite of its theatricality, and often magnificent in description.

In 1811 Châteaubriand was elected to the French Academy as the successor of the poet Chénier. Among his works not already mentioned are 'René' (1807), a sort of sequel to 'Atala'; 'The Martyrs' (1810); 'The Natchez' (1826), containing recollections of America; an 'Essay on English Literature' (2 vols.); and a translation of Milton's 'Paradise Lost' (1836).

CHRISTIANITY VINDICATED

From 'The Genius of Christianity'

During the reign of the Emperor Julian commenced a persecution, perhaps more dangerous than violence itself, which consisted in loading the Christians with disgrace and contempt. Julian began his hostility by plundering the churches; he then forbade the faithful to teach or to study the liberal arts and sciences. Sensible, however, of the important advantages of the institutions of Christianity, the emperor determined to establish hospitals and monasteries, and after the example of the gospel system to combine morality with religion; he ordered a kind of sermons to be delivered in the pagan temples....

From the time of Julian to that of Luther, the Church, flourishing in full vigor, had no occasion for apologists; but when the Western schism took place, with new enemies arose new defenders. It cannot be denied that at first the Protestants had the superiority, at least in regard to forms, as Montesquieu has remarked. Erasmus himself was weak when opposed to Luther, and Theodore Beza had a captivating manner of writing, in which his opponents were too often deficient....

It is natural for schism to lead to infidelity, and for heresy to engender atheism. Bayle and Spinoza arose after Calvin, and they found in Clarke and Leibnitz men of sufficient talents to refute their sophistry. Abbadie wrote an apology for religion, remarkable for method and sound argument. Unfortunately his style is feeble, though his ideas are not destitute of brilliancy. "If the ancient philosophers," observes Abbadie, "adored the Virtues, their worship was only a beautiful species of idolatry."