автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Library of the World's Best Literature, Ancient and Modern, Vol. 15

HOW KRIEMHILD IS LED TO ETZEL.

From the Hundeshagen Nibelungen manuscripts of the 10th century, in the Royal Library at Berlin.

"Let the messenger ride and thus we make Known to you how the queen rode the country."

Kriemhild is the legendary heroine of the "Nibelungenlied," and the rival of Brunhild. She was the wife of Siegfried who was slain by her brothers. Later, as the wife of Etzel (Attila) King of the Huns, she avenged the murder of Siegfried by compassing the death of her brothers, but was herself slain.

LIBRARY OF THE

WORLD'S BEST LITERATURE

ANCIENT AND MODERN

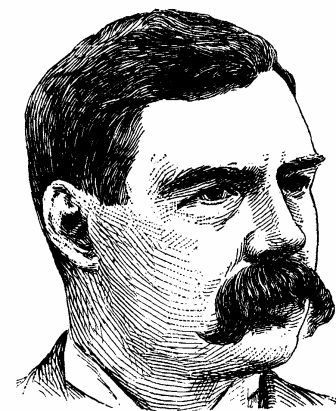

CHARLES DUDLEY WARNER

EDITOR

HAMILTON WRIGHT MABIE

LUCIA GILBERT RUNKLE

GEORGE HENRY WARNER

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Connoisseur Edition

Vol. XV.

NEW YORK

THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY

Connoisseur Edition

LIMITED TO FIVE HUNDRED COPIES IN HALF RUSSIA

No. ..........

Copyright, 1896, by

R. S. PEALE AND J. A. HILL

All rights reserved

THE ADVISORY COUNCIL

CRAWFORD H. TOY, A. M., LL. D.,

Professor of Hebrew, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

THOMAS R. LOUNSBURY, LL. D., L. H. D.,

Professor of English in the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

WILLIAM M. SLOANE, Ph. D., L. H. D.,

Professor of History and Political Science, Princeton University, Princeton, N. J.

BRANDER MATTHEWS, A. M., LL. B.,

Professor of Literature, Columbia University, New York City.

JAMES B. ANGELL, LL. D.,

President of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.

WILLARD FISKE, A. M., Ph. D.,

Late Professor of the Germanic and Scandinavian Languages and Literatures, Cornell University, Ithaca, N. Y.

EDWARD S. HOLDEN, A. M., LL. D.,

Director of the Lick Observatory, and Astronomer, University of California, Berkeley, Cal.

ALCÉE FORTIER, LIT. D.,

Professor of the Romance Languages, Tulane University, New Orleans, La.

WILLIAM P. TRENT, M. A.,

Dean of the Department of Arts and Sciences, and Professor of English and History, University of the South, Sewanee, Tenn.

PAUL SHOREY, Ph. D.,

Professor of Greek and Latin Literature, University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill.

WILLIAM T. HARRIS, LL. D.,

United States Commissioner of Education, Bureau of Education, Washington, D. C.

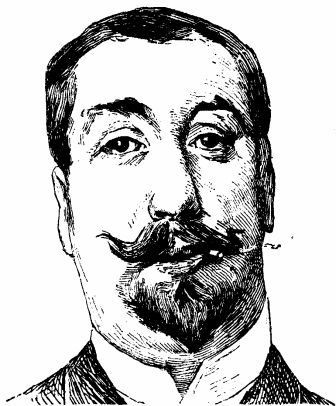

MAURICE FRANCIS EGAN, A. M., LL. D.,

Professor of Literature in the Catholic University of America, Washington, D. C.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

VOL. XV

LIVED PAGE Folk-Song 5853BY F. B. GUMMERE

Samuel Foote1720-1777

5878 How to be a Lawyer ('The Lame Lover') A Misfortune in Orthography (same) From the 'Memoirs': A Cure for Bad Poetry; The Retort Courteous; On Garrick's Stature; Cape Wine; The Graces; The Debtor; Affectation; Arithmetical Criticism; The Dear Wife; Garrick and the Guinea; Dr. Paul Hifferman; Foote and Macklin; Baron Newman; Mrs. Abington; Garlic-Eaters; Mode of Burying Attorneys in London; Dining Badly; Dibble Davis; An Extraordinary Case; Mutability of the World; An Appropriate Motto; Real Friendship; Anecdote of an Author; Dr. Blair; Advice to a Dramatic Writer; The Grafton Ministry John Ford1586-?

5889 From 'Perkin Warbeck' Penthea's Dying Song ('The Broken Heart') From 'The Lover's Melancholy': Amethus and Menaphon Friedrich, Baron de la Motte Fouqué1777-1843

5895 The Marriage of Undine ('Undine') The Last Appearance of Undine (same) Song from 'Minstrel Lore' Anatole France1844-

5909 In the Gardens ('The Crime of Sylvestre Bonnard') Child-Life ('The Book of my Friend') From the 'Garden of Epicurus' St. Francis d'Assisi1182-1226

5919BY MAURICE FRANCIS EGAN

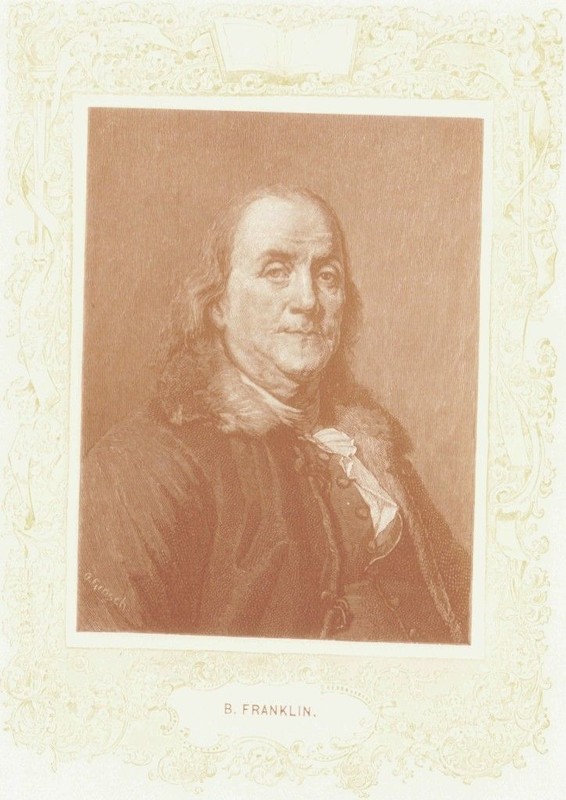

Order The Canticle of the Sun Benjamin Franklin1706-1790

5925BY JOHN BIGELOW

Of Franklin's Family and Early Life ('Autobiography') Franklin's Journey to Philadelphia: His Arrival There (same) Franklin as a Printer (same) Rules of Health ('Poor Richard's Almanack') The Way to Wealth (same) Speech in the Federal Convention, in Favor of Opening Its Sessions with Prayer On War Revenge: Letter to Madame Helvétius The Ephemera: an Emblem of Human Life A Prophecy (Letter to Lord Kames) Early Marriages (Letter to John Alleyne) The Art of Virtue ('Autobiography') Louis Honoré Fréchette1839-

5964BY MAURICE FRANCIS EGAN

Our History ('Le Légende d'un Peuple') Caughnawaga Louisiana ('Les Feuilles Volantes') The Dream of Life (same) Harold Frederic1856-?

5971 The Last Rite ('The Damnation of Theron Ware') Edward Augustus Freeman1823-1892

5977BY JOHN BACH M

cMASTER

The Altered Aspects of Rome ('Historical Essays') The Continuity of English History (same) Race and Language (same) The Norman Council and the Assembly of Lillebonne ('The History of the Norman Conquest of England') Ferdinand Freiligrath1810-1876

6002 The Emigrants The Lion's Ride Rest in the Beloved Oh, Love so Long as Love Thou Canst Gustav Freytag1816-1895

6011 The German Professor ('The Lost Manuscript') Friedrich Froebel1782-1852

6022BY NORA ARCHIBALD SMITH

The Right of the Child ('Reminiscences of Friedrich Froebel') Evolution ('The Mottoes and Commentaries of Mother Play') The Laws of the Mind ('The Letters of Froebel') For the Children (same) Motives ('The Education of Man') Aphorisms Froissart1337-1410?

6035BY GEORGE M

cLEAN HARPER

From the 'Chronicles': The Invasion of France by King Edward III., and the Battle of Crécy How the King of England Rode through Normandy Of the Great Assembly that the French King Made to Resist the King of England Of the Battle of Caen, and How the Englishmen Took the Town How the French King Followed the King of England in Beauvoisinois Of the Battle of Blanche-Taque Of the Order of the Englishmen at Cressy The Order of the Frenchmen at Cressy, and How They Beheld the Demeanor of the Englishmen Of the Battle of Cressy, August 26th, 1346 James Anthony Froude1818-1894

6059BY CHARLES FREDERICK JOHNSON

The Growth of England's Navy ('English Seamen in the Sixteenth Century') The Death of Colonel Goring ('Two Chiefs of Dunboy') Scientific Method Applied to History ('Short Studies on Great Subjects') The Death of Thomas Becket (same) Character of Henry VIII. ('History of England') On a Siding at a Railway Station ('Short Studies on Great Subjects') Henry B. Fuller1859-

6101 At the Head of the March ('With the Procession') Sarah Margaret Fuller(Marchioness Ossoli)

1810-1850

6119 George Sand ('Memoirs') Americans Abroad in Europe ('At Home and Abroad') A Character Sketch of Carlyle ('Memoirs') Thomas Fuller1608-1661

6129 The King's Children ('The Worthies of England') A Learned Lady (same) Henry de Essex, Standard-Bearer to Henry II. (same) The Good Schoolmaster ('The Holy and Profane State') On Books (same) London ('The Worthies of England') Miscellaneous Sayings Émile Gaboriau1835-1873

6137 The Impostor and the Banker's Wife: The Robbery ('File No. 113') M. Lecoq's System (same) Benito Perez Galdós1845-

6153BY WILLIAM HENRY BISHOP

The First Night of a Famous Play ('The Court of Charles IV.') Doña Perfecta's Daughter ('Doña Perfecta') Above Stairs in a Royal Palace ('La de Bringas') Francis Galton1822-

6174 The Comparative Worth of Different Races ('Hereditary Genius') Arne Garborg1851-

6185 The Conflict of the Creeds ('A Freethinker') Hamlin Garland1860-

6195 A Summer Mood ('Prairie Songs') A Storm on Lake Michigan ('Rose of Butcher's Coolly') Elizabeth Stevenson Gaskell1810-1865

6205 Our Society ('Cranford') Visiting (same) Théophile Gautier1811-1872

6221BY ROBERT SANDERSON

The Entry of Pharaoh into Thebes ('The Romance of a Mummy') From 'The Marsh' From 'The Dragon-Fly' The Doves The Pot of Flowers Prayer The Poet and the Crowd The First Smile of Spring The Veterans ('The Old Guard') John Gay1685-1732

6237 The Hare and Many Friends ('Fables') The Sick Man and the Angel (same) The Juggler (same) Sweet William's Farewell to Black-Eyed Susan From 'What D'ye Call It?' Emanuel von Geibel1815-1884

6248 See'st Thou the Sea? As it will Happen Gondoliera The Woodland Onward At Last the Daylight FadethFULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

VOLUME XV

PAGE "How Kreimhild is Led to Etzel" (Colored Plate)Frontispiece

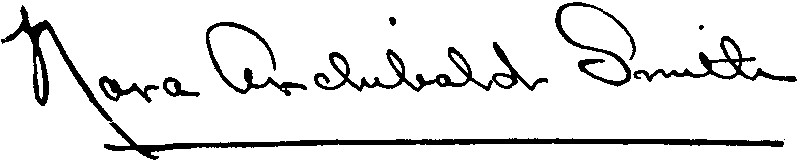

Russian Writing (Fac-simile) 5876 Franklin (Portrait) 5925 "Music, Science, and Art" (Photogravure) 5964 Freytag (Portrait) 6011 "The Menagerie" (Photogravure) 6034 "The Wedding Dress" (Photogravure) 6166 "The Juggler" (Photogravure) 6244VIGNETTE PORTRAITS

Foqué Froude France Fuller (Margaret) Frederic Fuller (Thomas) Freeman Garland Freiligrath Gaskell Froebel Gautier Froissart Gay Von GiebelFOLK-SONG

BY F. B. GUMMERE

But there is a more cheerful vein in this sort of song; and the mountain offers pleasanter views:—

Without religious preparation in childhood, no true religion and no union with God is possible for men.

"And who asks the author to introduce all this philosophy?" said the pedant. "What has the theatre to do with moralizing? In the 'Magician of Astrakhan,' in 'Leon and the Asturias Gave Heraldry to Spain,' and in the 'Triumphs of Don Pelayo'—plays that all the world admires—did you ever find a passage that describes how girls are to be brought up?"

s in the case of ballads, or narrative songs, it was important to sunder not only the popular from the artistic, but also the ballad of the people from the ballad for the people; precisely so in the article of communal lyric one must distinguish songs of the folk—songs made by the folk—from those verses of the street or the music hall which are often caught up and sung by the crowd until they pass as genuine folk-song. For true folk-song, as for the genuine ballad, the tests are simplicity, sincerity, mainly oral tradition, and origin in a homogeneous community. The style of such a poem is not only simple, but free from individual stamp; the metaphors, employed sparingly at the best, are like the phrases which constantly occur in narrative ballads, and belong to tradition. The metre is not so uniform as in ballads, but must betray its origin in song. An unsung folk-song is more than a contradiction,—it is an impossibility. Moreover, it is to be assumed that primitive folk-songs were an outcome of the dance, for which originally there was no music save the singing of the dancers. A German critic declares outright that for early times there was "no dance without singing, and no song without a dance; songs for the dance were the earliest of all songs, and melodies for the dance the oldest music of every race." Add to this the undoubted fact that dancing by pairs is a comparatively modern invention, and that primitive dances involved the whole able-bodied primitive community (Jeanroy's assertion that in the early Middle Ages only women danced, is a libel on human nature), and one begins to see what is meant by folk-song; primarily it was made by the singing and dancing throng, at a time when no distinction of lettered and unlettered classes divided the community. Few, if any, of these primitive folk-songs have come down to us; but they exist in survival, with more or less trace of individual and artistic influences. As we cannot apply directly the test of such a communal origin, we must cast about for other and more modern conditions.

When Mr. George Saintsbury deplores "the lack, notorious to this day, of one single original English folk-song of really great beauty," he leaves his readers to their own devices by way of defining this species of poetry. Probably, however, he means the communal lyric in survival, not the ballad, not what Germans would include under volkslied and Frenchmen under chanson populaire. This distinction, so often forgotten by our critics, was laid down for English usage a century ago by no less a person than Joseph Ritson. "With us," he said, "songs of sentiment, expression, or even description, are properly called Songs, in contradistinction to mere narrative compositions, which now denominate Ballads."

Notwithstanding this lucid statement, we have failed to clear the field of all possible causes for error. The song of the folk is differentiated from the song of the individual poet; popular lyric is set over against the artistic, personal lyric. But lyric is commonly assumed to be the expression of individual emotion, and seems in its very essence to exclude all that is not single, personal, and conscious emotion. Professor Barrett Wendell, however, is fain to abandon this time-honored notion of lyric as the subjective element in poetry, the expression of individual emotion, and proposes a definition based upon the essentially musical character of these songs. If we adhere strictly to the older idea, communal lyric, or folk-song, is a contradiction in terms; but as a musical expression, direct and unreflective, of communal emotion, and as offspring of the enthusiasm felt by a festal, dancing multitude, the term is to be allowed. It means the lyric of a throng. Unless one feels this objective note in a lyric, it is certainly no folk-song, but merely an anonymous product of the schools. The artistic and individual lyric, however sincere it may be, is fairly sure to be blended with reflection; but such a subjective tone is foreign to communal verse—whether narrative or purely lyrical. In other words, to study the lyric of the people, one must banish that notion of individuality, of reflection and sentiment, which one is accustomed to associate with all lyrics. To illustrate the matter, it is evident that Shelley's 'O World, O Life, O Time,' and Wordsworth's 'My Heart Leaps Up,' however widely sundered may be the points of view, however varied the character of the emotion, are of the same individual and reflective class. Contrast now with these a third lyric, an English song of the thirteenth century, preserved by some happy chance from the oblivion which claimed most of its fellows; the casual reader would unhesitatingly put it into the same class with Wordsworth's verses as a lyric of "nature," of "joy," or what not,—an outburst of simple and natural emotion. But if this 'Cuckoo Song' be regarded critically, it will be seen that precisely those qualities of the individual and the subjective are wanting. The music of it is fairly clamorous; the refrain counts for as much as the verses; while the emotion seems to spring from the crowd and to represent a community. Written down—no one can say when it was actually composed—not later than the middle of the thirteenth century, along with the music and a Latin hymn interlined in red ink, this song is justly regarded by critics as communal rather than artistic in its character; and while it is set to music in what Chappell calls "the earliest secular composition, in parts, known to exist in any country," yet even this elaborate music was probably "a national song and tune, selected according to the custom of the times as a basis for harmony," and was "not entirely a scholastic composition." It runs in the original:—

Sumer is icumen in. Lhude sing cuccu. Groweth sed And bloweth med And springth the wde nu. Sing cuccu.

Awe bleteth after lomb, Lhouth after calve cu; Bulluc sterteth, Bucke verteth, Murie sing cuccu. Cuccu, cuccu.

Wel singes thu cuccu, Ne swik thu naver nu.

Burden

Sing cuccu nu. Sing cuccu. Sing cuccu. Sing cuccu nu.[1]

The monk, whose passion for music led him to rescue this charming song, probably regretted the rustic quality of the words, and did his best to hide the origin of the air; but behind the complicated music is a tune of the country-side, and if the refrain is here a burden, to be sung throughout the piece by certain voices while others sing the words of the song, we have every right to think of an earlier refrain which almost absorbed the poem and was sung by a dancing multitude. This is a most important consideration. In all parts of Europe, songs for the dance still abound in the shape of a welcome to spring; and a lyrical outburst in praise of the jocund season often occurs by way of prelude to the narrative ballad: witness the beautiful opening of 'Robin Hood and the Monk.' The troubadour of Provence, like the minnesinger of Germany, imitated these invocations to spring. A charming balada of Provence probably takes us beyond the troubadour to the domain of actual folk-song.[2] "At the entrance of the bright season," it runs, "in order to begin joy and to tease the jealous, the queen will show that she is fain to love. As far as to the sea, no maid nor youth but must join the lusty dance which she devises. On the other hand comes the king to break up the dancing, fearful lest some one will rob him of his April queen. Little, however, cares she for the graybeard; a gay young 'bachelor' is there to pleasure her. Whoso might see her as she dances, swaying her fair body, he could say in sooth that nothing in all the world peers the joyous queen!" Then, as after each stanza, for conclusion the wild refrain—like a procul este, profani!—"Away, ye jealous ones, away! Let us dance together, together let us dance!" The interjectional refrain, "eya," a mere cry of joy, is common in French and German songs for the dance, and gives a very echo of the lusty singers. Repetition, refrain, the infectious pace and merriment of this old song, stamp it as a genuine product of the people.[3] The brief but emphatic praise of spring with which it opens is doubtless a survival of those older pagan hymns and songs which greeted the return of summer and were sung by the community in chorus to the dance, now as a religious rite, now merely as the expression of communal rejoicing. What the people once sang in chorus was repeated by the individual poet. Neidhart the German is famous on account of his rustic songs for the dance, which often begin with this lusty welcome to spring: while the dactyls of Walther von der Vogelweide not only echo the cadence of dancing feet, but so nearly exclude the reflective and artistic element that the "I" of the singer counts for little. "Winter," he sings,—

Winter has left us no pleasure at all; Leafage and heather have fled with the fall, Bare is the forest and dumb as a thrall; If the girls by the roadside were tossing the ball, I could prick up my ears for the singing-birds' call![4]

That is, "if spring were here, and the girls were going to the village dance"; for ball-playing was not only a rival of the dance, but was often combined with it. Walther's dactyls are one in spirit with the fragments of communal lyric which have been preserved for us by song-loving "clerks" or theological students, those intellectual tramps of the Middle Ages, who often wrote down such a merry song of May and then turned it more or less freely into their barbarous but not unattractive Latin. For example:—

Now is time for holiday! Let our singing greet the May: Flowers in the breezes play, Every holt and heath is gay.

Let us dance and let us spring With merry song and crying! Joy befits the lusty May: Set the ball a-flying! If I woo my lady-love, Will she be denying?[5]

The steps of the dance are not remote; and the same echo haunts another song of the sort:—

Dance we now the measure, Dance, lady mine! May, the month of pleasure, Comes with sweet sunshine.

Winter vexed the meadow Many weary hours: Fled his chill and shadow,— Lo, the fields are laughing Red with flowers.[6]

Or the song at the dance may set forth some of the preliminaries, as when a girl is supposed to sing:—

Care and sorrow, fly away! On the green field let us play, Playmates gentle, playmates mine, Where we see the bright flowers shine, I say to thee, I say to thee, Playmate mine, O come with me!

Gracious Love, to me incline, Make for me a garland fine,— Garland for the man to wear Who can please a maiden fair. I say to thee, I say to thee, Playmate mine, O come with me![7]

The greeting from youth to maiden, from maiden to youth, was doubtless a favorite bit of folk-song, whether at the dance or as independent lyric. Readers of the 'Library' will find such a greeting incorporated in 'Child Maurice'[8]; only there it is from the son to his mother, and with a somewhat eccentric list of comparisons by way of detail, instead of the terse form known to German tradition:—

Soar, Lady Nightingale, soar above! A hundred thousand times greet my love!

The variations are endless; one of the earliest is found in a charming Latin tale of the eleventh century, 'Rudlieb,' "the oldest known romance in European literature." A few German words are mixed with the Latin; while after the good old ballad way the greeting is first given to the messenger, and repeated when the messenger performs his task:—"I wish thee as much joy as there are leaves on the trees,—and as much delight as birds have, so much love (minna),—and as much honor I wish thee as there are flowers and grass!" Competent critics regard this as a current folk-song of greeting inserted in the romance, and therefore as the oldest example of minnesang in German literature. Of the less known variations of this theme, one may be given from the German of an old song where male singers are supposed to compete for a garland presented by the maidens; the rivals not only sing for the prize but even answer riddles. It is a combination of game and dance, and is evidently of communal origin. The honorable authorities of Freiburg, about 1556, put this practice of "dancing of evenings in the streets, and singing for a garland, and dancing in a throng" under strictest ban. The following is a stanza of greeting in such a song:—

Maiden, thee I fain would greet, From thy head unto thy feet. As many times I greet thee even As there are stars in yonder heaven, As there shall blossom flowers gay, From Easter to St. Michael's day![9]

These competitive verses for the dance and the garland were, as we shall presently see, spontaneous: composed in the throng by lad or lassie, they are certainly entitled to the name of communal lyric. Naturally, the greeting could ban as well as bless; and little Kirstin (Christina) in the Danish ballad sends a greeting of double charge:—

To Denmark's King wish as oft good-night As stars are shining in heaven bright; To Denmark's Queen as oft bad year As the linden hath leaves or the hind hath hair![10]

Folk-song in the primitive stage always had a refrain or chorus. The invocation of spring, met in so many songs of later time, is doubtless a survival of an older communal chorus sung to deities of summer and flooding sunshine and fertility. The well-known Latin 'Pervigilium Veneris,' artistic and elaborate as it is in eulogy of spring and love, owes its refrain and the cadence of its trochaic rhythm to some song of the Roman folk in festival; so that Walter Pater is not far from the truth when he gracefully assumes that the whole poem was suggested by this refrain "caught from the lips of the young men, singing because they could not help it, in the streets of Pisa," during that Indian summer of paganism under the Antonines. This haunting refrain, with its throb of the spring and the festal throng, is ruthlessly tortured into a heroic couplet in Parnell's translation:—

Let those love now who never loved before; Let those who always loved now love the more!

Contrast the original!—

Cras amet qui nunquam amavit; quique amavit cras amet!

This is the trochaic rhythm dear to the common people of Rome and the near provinces, who as every one knows spoke a very different speech from the speech of the patrician, and sang their own songs withal; a few specimens of the latter, notably the soldiers' song about Cæsar, have come down to us.[11]

The refrain itself, of whatever metre, was imitated by classical poets like Catullus; and the earliest traditions of Greece tell of these refrains, with gathering verses of lyric or narrative character, sung in the harvest-field and at the dance. In early Assyrian poetry, even, the refrain plays an important part; while an Egyptian folk-song, sung by the reapers, seems to have been little else than a refrain. Towards the end of the Middle Ages, courtly poets took up the refrain, experimented with it, refined it, and so developed those highly artificial forms of verse known as roundel, triolet, and ballade. The refrain, in short, is corner-stone for all poetry of the people, if not of poetry itself; beginning with inarticulate cries of joy or sorrow, like the eya noted above, mere emotional utterances or imitations of various sounds, then growing in distinctness and compass, until the separation of choral from artistic poetry, and the increasing importance of the latter, reduced the refrain to a merely ancillary function, and finally did away with it altogether. Many refrains are still used for the dance which are mere exclamations, with just enough coherence of words added to make them pass as poetry. Frequently, as in the French, these have a peculiar beauty. Victor Hugo has imitated them with success; but to render them into English is impossible.

The refrain, moreover, is closely allied to those couplets or quatrains composed spontaneously at the dance or other merry-making of the people. In many parts of Germany, the dances of harvest were until recent days enlivened by the so-called schnaderhüpfl, a quatrain sung to a simple air, composed on the spot, and often inclining to the personal and the satiric. In earlier days this power to make a quatrain off-hand seems to have been universal among the peasants of Europe. In Scandinavia such quatrains are known as stev. They are related, so far as their spontaneity, their universal character, and their origin are concerned, to the coplas of Spain, the stornelli of Italy, and the distichs of modern Greece. Of course, the specimens of this poetry which can be found now are rude enough; for the life has gone out of it, and to find it at its best one must go back to conditions which brought the undivided genius of the community into play. What one finds nowadays is such motley as this,—a so-called rundâ from Vogtland, answering to the Bavarian schnaderhüpfl:—

I and my Hans, We go to the dance; And if no one will dance, Dance I and my Hans!

A schnaderhüpfl taken down at Appenzell in 1754, and one of the oldest known, was sung by some lively girl as she danced at the reapers' festival:—

Mine, mine, mine,—O my love is fine, And my favor shall he plainly see; Till the clock strike eight, till the clock strike nine, My door, my door shall open be.

It is evident that the great mass of this poetry died with the occasion that brought it forth, or lingered in oral tradition, exposed to a thousand chances of oblivion. The Church made war upon these songs, partly because of their erotic character, but mainly, one may assume, because of the chain of tradition from heathen times which linked them with feasts in honor of abhorred gods, and with rustic dances at the old pagan harvest-home. A study of all this, however, with material at a minimum, and conjecture or philological combination as the only possible method of investigation, must be relegated to the treatise and the monograph;[12] for present purposes we must confine our exposition and search to songs that shall attract readers as well as students. Yet this can be done only by the admission into our pages of folk-song which already bears witness, more or less, to the touch of an artist working upon material once exclusively communal and popular.

Returning to our English type, the 'Cuckoo Song,' we are now to ask what other communal lyrics with this mark upon them, denoting at once rescue and contamination at the hands of minstrel or wandering clerk, have come down to us from the later Middle Ages. Having answered this question, it will remain to deal with the difficult material accumulated in comparatively recent times. Ballads are far easier to preserve than songs. Ballads have a narrative; and this story in them has proved antiseptic, defying the chances of oral transmission. A good story travels far, and the path which it wanders from people to people is often easy to follow; but the more volatile contents of the popular lyric—we are not speaking of its tune, which is carried in every direction—are easily lost.[13] Such a lyric lives chiefly by its sentiment, and sentiment is a fragile burden. We can however get some notion of this communal song by process of inference, for the earliest lays of the Provençal troubadour, and probably of the German minnesinger, were based upon the older song of the country-side. Again, in England there was little distinction made between the singer who entertained court and castle and the gleeman who sang in the villages and at rural festivals; the latter doubtless taking from the common stock more than he contributed from his own. A certain proof of more aristocratic and distinctly artistic, that is to say, individual origin, and a conclusive reason for refusing the name of folk-song to any one of these lyrics of love, is the fact that it happens to address a married woman. Every one knows that the troubadour and the minnesinger thus addressed their lays; and only the style and general character of their earliest poetry can be considered as borrowed from the popular muse. In other words, however vivacious, objective, vigorous, may be the early lays of the troubadour, however one is tempted to call them mere modifications of an older folk-song, they are excluded by this characteristic from the popular lyric and belong to poetry of the schools. Marriage, says Jeanroy, is always respected in the true folk-song. Moreover, this is only a negative test. In Portugal, many songs which must be referred to the individual and courtly poet are written in praise of the unmarried girl; while in England, whether it be set down to austere morals or to the practical turn of the native mind, one finds little or nothing to match this troubadour and minnesinger poetry in honor of the stately but capricious dame.[14] The folk-song that we seek found few to record it; it sounded at the dance, it was heard in the harvest-field; what seemed to be everywhere, growing spontaneously like violets in spring, called upon no one to preserve it and to give it that protection demanded by exotic poetry of the schools. What is preserved is due mainly to the clerks and gleemen of older times, or else to the curiosity of modern antiquarians, rescuing here and there a belated survival of the species. Where the clerk or the gleeman is in question, he is sure to add a personal element, and thus to remove the song from its true communal setting. Contrast the wonderful little song, admired by Alceste in Molière's 'Misanthrope,' and as impersonal, even in its first-personal guise as any communal lyric ever made,—with a reckless bit of verse sung by some minstrel about the famous Eleanor of Poitou, wife of Henry II. of England. The song so highly commended by Alceste[15] runs, in desperately inadequate translation:—

If the King had made it mine, Paris, his city gay, And I must the love resign Of my bonnie may,[16]—

To King Henry I would say: Take your Paris back, I pray; Better far I love my may,— O joy!— Love my bonnie may!

Let us hear the reckless "clerk":—

If the whole wide world were mine, From the ocean to the Rhine, All I'd be denying If the Queen of England once In my arms were lying![17]

The tone is not directly communal, but it smacks more of the village dance than of the troubadour's harp; for even Bernart of Ventadour did not dare to address Eleanor save in the conventional tone of despair. The clerks and gleemen, however, and even English peasants of modern times,[18] took another view of the matter. The "clerk," that delightful vagabond who made so nice a balance between church and tavern, between breviary and love songs, has probably done more for the preservation of folk-song than all other agents known to us. In the above verses he protests a trifle or so too much about himself; let us hear him again as mere reporter for the communal lyric, in verses that he may have brought from the dance to turn into his inevitable Latin:—

Come, my darling, come to me, I am waiting long for thee,— I am waiting long for thee, Come, my darling, come to me!

Rose-red mouth, so sweet and fain, Come and make me well again;— Come and make me well again, Rose-red mouth, so sweet and fain.[19]

More graceful yet are the anonymous verses quoted in certain Latin love-letters of a manuscript at Munich; and while a few critics rebel at the notion of a folk-song, the pretty lines surely hint more of field and dance than of the study.

Thou art mine, I am thine, Of that may'st certain be; Locked thou art Within my heart, And I have lost the key: There must thou ever be!

Now it happens that this notion of heart and key recurs in later German folk-song. A highly popular song of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries has these stanzas:[20]

For thy dear sake I'm hither come, Sweetheart, O hear me woo! My hope rests evermore on thee, I love thee well and true. Let me but be thy servant, Thy dear love let me win; Come, ope thy heart, my darling, And lock me fast within!

Where my love's head is lying, There rests a golden shrine; And in it lies, locked hard and fast, This fresh young heart of mine: Oh would to God I had the key,— I'd throw it in the Rhine; What place on earth were more to me, Than with my sweeting fine?

Where my love's feet are lying, A fountain gushes cold, And whoso tastes the fountain Grows young and never old: Full often at the fountain I knelt and quenched my drouth,— Yet tenfold rather would I kiss My darling's rosy mouth!

And in my darling's garden[21] Is many a precious flower; Oh, in this budding season, Would God 'twere now the hour To go and pluck the roses And nevermore to part: I think full sure to win her Who lies within my heart!

Now who this merry roundel Hath sung with such renown? That have two lusty woodsmen At Freiberg in the town,— Have sung it fresh and fairly, And drunk the cool red wine: And who hath sat and listened?— Landlady's daughter fine!

What with the more modern tone, and the lusty woodsmen, one has deserted the actual dance, the actual communal origin of song; but one is still amid communal influences. Another little song about the heart and the key, this time from France, recalls one to the dance itself, and to the simpler tone:—

Shut fast within a rose I ween my heart must be; No locksmith lives in France Who can set it free,— Only my lover Pierre, Who took away the key![22]

Coming back to England, and the search for her folk-song, it is in order to begin with the refrain. A "clerk," in a somewhat artificial lay to his sweetheart, has preserved as refrain what seems to be a bit of communal verse:—

Ever and aye for my love I am in sorrow sore; I think of her I see so seldom any more,[23]—

rather a helpless moan, it must be confessed.

Better by far is the song of another clericus, with a lusty little refrain as fresh as the wind it invokes, as certainly folk-song as anything left to us:—

Blow, northern wind, Send thou me my sweeting! Blow, northern wind, Blow, blow, blow!

The actual song, though overloaded with alliteration, has a good movement. A stanza may be quoted:—

I know a maid in bower so bright That handsome is for any sight, Noble, gracious maid of might, Precious to discover.

In all this wealth of women fair, Maid of beauty to compare With my sweeting found I ne'er All the country over!

Old too is the lullaby used as a burden or refrain for a religious poem printed by Thomas Wright in his 'Songs and Carols':—

Lullay, myn lykyng, my dere sone, myn swetyng, Lullay, my dere herte, myn owyn dere derlyng.[24]

The same English manuscript which has kept the refrain 'Blow, Northern Wind,' offers another song which may be given in modern translation and entire. All these songs were written down about the year 1310, and probably in Herefordshire. As with the carmina burana, the lays of German "clerks," so these English lays represent something between actual communal verse and the poetry of the individual artist; they owe more to folk-song than to the traditions of literature and art. Some of the expressions in this song are taken, if we may trust the critical insight of Ten Brink, directly from the poetry of the people.

A maid as white as ivory bone, A pearl in gold that golden shone, A turtle-dove, a love whereon My heart must cling: Her blitheness nevermore be gone While I can sing!

When she is gay, In all the world no more I pray Than this: alone with her to stay Withouten strife. Could she but know the ills that slay Her lover's life!

Was never woman nobler wrought; And when she blithe to sleep is brought, Well for him who guessed her thought, Proud maid! Yet O, Full well I know she will me nought. My heart is woe.

And how shall I then sweetly sing That thus am marréd with mourning? To death, alas, she will me bring Long ere my day. Greet her well, the sweetë thing, With eyen gray!

Her eyes have wounded me, i-wis. Her arching brows that bring the bliss; Her comely mouth whoso might kiss, In mirth he were; And I would change all mine for his That is her fere.[25]

Her fere, so worthy might I be, Her fere, so noble, stout and free, For this one thing I would give three, Nor haggle aught. From hell to heaven, if one could see, So fine is naught, [Nor half so free;[26] All lovers true, now listen unto me.]

Now hearken to me while I tell, In such a fume I boil and well; There is no fire so hot in hell As his, I trow, Who loves unknown and dares not tell His hidden woe.

I will her well, she wills me woe; I am her friend, and she my foe; Methinks my heart will break in two For sorrow's might; In God's own greeting may she go, That maiden white!

I would I were a throstlecock, A bunting, or a laverock,[27] Sweet maid! Between her kirtle and her smock I'd then be hid!

The reader will easily note the struggle between our poet's conventional and quite literary despair and the fresh communal tone in such passages as we have ventured, despite Leigh Hunt's direful example, to put in italics. This poet was a clerk, or perhaps not even that,—a gleeman; and he dwells, after the manner of his kind, upon a despair which springs from difference of station. But it is England, not France; it is a maiden, not countess or queen, whom he loves; and the tone of his verse is sound and communal at heart. True, the metre, afterwards a favorite with Burns, is one used by the oldest known troubadour of Provence, Count William, as well as by the poets of miracle plays and of such romances as the English 'Octavian'; but like Count William himself, who built on a popular basis, our clerk or gleeman is nearer to the people than to the schools. Indeed, Uhland reminds us that Breton kloer ("clerks") to this day play a leading part as lovers and singers of love in folk-song; and the English clerks in question were not regular priests, consecrated and in responsible positions, but students or unattached followers of theology. They sang with the people; they felt and suffered with the people—as in the case of a far nobler member of the guild, William Langland; and hence sundry political poems which deal with wrongs and suffering endured by the commons of that day. In the struggle of barons and people against Henry III., indignation made verses; and these, too, we owe to the clerks. Such a burst of indignation is the song against Richard of Cornwall, with a turbulent refrain which sounds like a direct loan from the people. One stanza, with this refrain, will suffice. It opens with the traditional "lithe and listen" of the ballad-singer:—

Sit all now still and list to me: The German King, by my loyalty! Thirty thousand pound asked he To make a peace in this country,— And so he did and more!

Refrain

Richard, though thou be ever trichard,[28] Trichen[29] shalt thou nevermore!

This, however, like many a scrap of battle-song, ribaldry exchanged between two armies, and the like, has interest rather for the antiquarian than for the reader. We shall leave such fragments, and turn in conclusion to the folk-song of later times.

The England of Elizabeth was devoted to lyric poetry, and folk-song must have flourished along with its rival of the schools. Few of these songs, however, have been preserved; and indeed there is no final test for the communal quality in such survivals. Certainly some of the songs in the drama of that time are of popular origin; but the majority, as a glance at Mr. Bullen's several collections will prove, are artistic and individual, like the music to which they were sung. Occasionally we get a tantalizing glimpse of another lyrical England, the folk dancing and singing their own lays; but no Autolycus brings these to us in his basket. Even the miracle plays had not despised folk-song; unfortunately the writers are content to mention the songs, like our Acts of Congress, only by title. In the "comedy" called 'The Longer Thou Livest the More Foole Thou Art,' there are snatches of such songs; and a famous list, known to all scholars, is given by Laneham in a letter from Kenilworth in 1575, where he tells of certain songs, "all ancient," owned by one Captain Cox. Again, nobody ever praised songs of the people more sincerely than Shakespeare has praised them; and we may be certain that he used them for the stage. Such is the 'Willow Song' that Desdemona sings,—an "old thing," she calls it; and such perhaps the song in 'As You Like It,'—'It Was a Lover and His Lass.' Nash is credited with the use of folk-songs in his 'Summer's Last Will and Testament'; but while the pretty verses about spring and the tripping lines, 'A-Maying,' have such a note, nothing could be further from the quality of folk-song than the solemn and beautiful 'Adieu, Farewell, Earth's Bliss.' In Beaumont and Fletcher's 'Knight of the Burning Pestle,' however, Merrythought sings some undoubted snatches of popular lyric, just as he sings stanzas from the traditional ballad; for example, his—

[1] For facsimile of the MS., music, and valuable remarks, see Chappell, 'Ballad Literature and Popular Music of the Olden Time,' Vol. i., frontispiece, and pages 21 ff. For pronunciation, see A. J. Ellis, 'Early English Pronunciation,' ii., 419 ff. The translation given by Mr. Ellis is:—

[2] The first stanza in the original will show the structure of this true "ballad" in the primitive sense of a dance-song. There are five of these stanzas, carrying the same rhymes throughout:—

[3] Games and songs of children are still to be found which preserve many of the features of these old dance-songs. The dramatic traits met with in the games point back now to the choral poetry of pagan times, when perhaps a bit of myth was enacted, now to the communal dance where the stealing of a bride may have been imitated.

[4] Unless otherwise credited, translations are by the writer.

[5] From 'Carmina Burana,' a collection of these songs in Latin and German preserved in a MS. of the thirteenth century; edited by J. A. Schmeller, Breslau, 1883. This song is page 181 ff., in German, 'Nu Suln Wir Alle Fröude Hân.'

[6] Ibid., page 178: 'Springe wir den Reigen.'

[7] Ibid., page 213: 'Ich wil Trûren Varen lân.'

[8] Article in 'Ballads,' Vol. iii., page 1340.

[9] Uhland, 'Volkslieder,' i. 12.

[10] Grundtvig, 'Danmarks Gamle Folkeviser,' iii. 161.

[11] We cannot widen our borders so as to include that solitary folk-song rescued from ancient Greek literature, the 'Song of the Swallow,' sung by children of the Island of Rhodes as they went about asking gifts from house to house at the coming of the earliest swallow. The metre is interesting in comparison with the rhythm of later European folk-songs, and there is evident dramatic action. Nor can we include the fragments of communal drama found in the favorite Debates Between Summer and Winter,—from the actual contest, to such lyrical forms as the song at the end of Shakespeare's 'Love's Labor's Lost.' The reader may be reminded of a good specimen of this class in 'Ivy and Holly,' printed by Ritson, 'Ancient Songs and Ballads,' Hazlitt's edition, page 114 ff., with the refrain:—

[12] Folk-lore, mythology, sociology even, must share in this work. The reader may consult for indirect but valuable material such books as Frazer's 'Golden Bough,' or that admirable treatise, Tylor's 'Primitive Culture.'

[13] For early times translation from language to language is out of the question, certainly in the case of lyrics. It is very important to remember that primitive man regarded song as a momentary and spontaneous thing.

[14] Yet even rough Scandinavia took up this brilliant but doubtful love poetry. To one of the Norse kings is attributed a song in which the royal singer informs his "lady" by way of credentials for his wooing,—"I have struck a blow in the Saracen's land; let thy husband do the same!"

[15] 'Le Misanthrope,' i. 2; he calls it a vielle chanson. M. Tiersot concedes it to the popular muse, but thinks it is of the city, not of the country.

[16] May, a favorite ballad word for "maid," "sweetheart."

[17] 'Carm. Bur.,' page 185: "Wær diu werlt alliu mîn."

[18] See Child's Ballads, vi. 257, and Grandfer Cantle's ballad in Mr. Hardy's 'Return of the Native.' See next page.

[19] 'Carm. Bur.,' page 208: "Kume, Kume, geselle min."

[20] Translated from Böhme 'Altdeutsches Liederbuch,' Leipzig, 1877, page 233. Lovers of folk-song will find this book invaluable on account of the carefully edited musical accompaniments. With it and Chappell, the musician has ample material for English and German songs; for French, see Tiersot, 'La Chanson Populaire en France.'

[21] The garden in these later songs is constantly a symbol of love. To pluck the roses, etc., is conventional for making love.

[22] Quoted by Tiersot, page 88, from 'Chansons à Danser en Rond,' gathered before 1704.

[23] Böddeker's 'Old Poems from the Harleian MS. 2253,' with notes, etc., in German; Berlin, 1878, page 179.

[24] See also Ritson, 'Ancient Songs and Ballads,' 3rd Ed., pages xlviii., 202 ff. The Percy folio MS. preserved a cradle song, 'Balow, my Babe, ly Still and Sleepe,' which was published as a broadside, and finally came to be known as 'Lady Anne Bothwell's Lament.' These "balow" lullabies are said by Mr. Ebbsworth to be imitations of a pretty poem first published in 1593, and now printed by Mr. Bullen in his 'Songs from Elizabethan Romances,' page 92.

[25] Fere, companion, lover. "I would give all I have to be her lover."

[26] Superfluous verses; but the MS. makes no distinction. Free means noble, gracious. "If one could see everything between hell and heaven, one would find nothing so fair and noble."

[27] Lark. The poem is translated from Böddeker, page 161 ff.

[28] Traitor.

[29] Betray.

Go from my window, love, go; Go from my window, my dear; The wind and the rain Will drive you back again, You cannot be lodged here,—

is quoted with variations in other plays, and was a favorite of the time,[30] and like many a ballad appears in religious parody. A modern variant, due to tradition, comes from Norwich; the third and fourth lines ran:—

For the wind is in the west, And the cuckoo's in his nest.

From the time of Henry VIII. a pretty song is preserved of this same class:—

Westron wynde, when wyll thou blow! The smalle rain downe doth rayne; Oh if my love were in my armys, Or I in my bed agayne!

This sort of song between the lovers, one without and one within, occurs in French and German at a very early date, and is probably much older than any records of it; as serenade, it found great favor with poets of the city and the court, and is represented in English by Sidney's beautiful lines, admirable for purposes of comparison with the folk-song:—

"Who is it that this dark night Underneath my window plaineth?" "It is one who, from thy sight Being, ah, exiled! disdaineth Every other vulgar light."

The zeal of modern collectors has brought together a mass of material which passes for folk-song. None of it is absolutely communal, for the conditions of primitive lyric have long since been swept away; nevertheless, where isolated communities have retained something of the old homogeneous and simple character, the spirit of folk-song lingers in survival. From Great Britain, from France, and particularly from Germany, where circumstances have favored this survival, a few folk-songs may now be given in inadequate translation. To go further afield, to collect specimens of Italian, Russian, Servian, modern Greek, and so on, would need a book. The songs which follow are sufficiently representative for the purpose.

A pretty little song, popular in Germany to this day, needs no pompous support of literary allusion to explain its simple pathos; still, it is possible that one meets here a distant echo of the tragedy of obstacles told in romance of Hero and Leander. When one hears this song, one understands where Heine found the charm of his best lyrics:—

Over a waste of water The bonnie lover crossed, A-wooing the King's daughter: But all his love was lost.

Ah, Elsie, darling Elsie, Fain were I now with thee; But waters twain are flowing, Dear love, twixt thee and me![31]

Even more of a favorite is the song which represents two girls in the harvest-field, one happy in her love, the other deserted; the noise of the sickle makes a sort of chorus. Uhland placed with the two stanzas of the song a third stanza which really belongs to another tune; the latter, however, may serve to introduce the situation:—

I heard a sickle rustling, Ay, rustling through the corn: I heard a maiden sobbing Because her love was lorn.

"Oh let the sickle rustle! I care not how it go; For I have found a lover, A lover, Where clover and violets blow."

"And hast thou found a lover Where clover and violets blow? I stand here, ah, so lonely, So lonely, And all my heart is woe!"

Two songs may follow, one from France, one from Scotland, bewailing the death of lover or husband. 'The Lowlands of Holland' was published by Herd in his 'Scottish Songs.'[32] A clumsy attempt was made to fix the authorship upon a certain young widow; but the song belies any such origin. It has the marks of tradition:—

My love has built a bonny ship, and set her on the sea, With sevenscore good mariners to bear her company; There's threescore is sunk, and threescore dead at sea, And the Lowlands of Holland has twin'd[33] my love and me.

My love he built another ship, and set her on the main, And nane but twenty mariners for to bring her hame, But the weary wind began to rise, and the sea began to rout; My love then and his bonny ship turned withershins[34] about.

There shall neither coif come on my head nor comb come in my hair; There shall neither coal nor candle-light come in my bower mair; Nor will I love another one until the day I die, For I never loved a love but one, and he's drowned in the sea.

"O haud your tongue, my daughter dear, be still and be content; There are mair lads in Galloway, ye neen nae sair lament." O there is none in Gallow, there's none at a' for me; For I never loved a love but one, and he's drowned in the sea.

The French song[35] has a more tender note:—

Low, low he lies who holds my heart, The sea is rolling fair above; Go, little bird, and tell him this,— Go, little bird, and fear no harm,— Say I am still his faithful love, Say that to him I stretch my arms.

Another song, widely scattered in varying versions throughout France, is of the forsaken and too trustful maid,—'En revenant des Noces.' The narrative in this, as in the Scottish song, makes it approach the ballad.

Back from the wedding-feast, All weary by the way,

I rested by a fount And watched the waters' play;

And at the fount I bathed, So clear the waters' play;

And with a leaf of oak I wiped the drops away.

Upon the highest branch Loud sang the nightingale.

Sing, nightingale, oh sing, Thou hast a heart so gay!

Not gay, this heart of mine: My love has gone away,

Because I gave my rose Too soon, too soon away.

Ah, would to God that rose Yet on the rosebush lay,—

Would that the rosebush, even, Unplanted yet might stay,—

Would that my lover Pierre My favor had to pray![36]

The corresponding Scottish song, beautiful enough for any land or age, is the well-known 'Waly, Waly':—

Oh waly, waly, up the bank, And waly, waly, down the brae, And waly, waly, yon burn-side, Where I and my love wont to gae.

I lean'd my back unto an aik, I thought it was a trusty tree; But first it bowed and syne it brak, Sae my true-love did lightly[37] me.

Oh waly, waly, but love be bonny A little time, while it is new; But when 'tis auld it waxeth cauld, And fades away like morning dew.

Oh wherefore should I busk my head? Or wherefore should I kame my hair? For my true-love has me forsook, And says he'll never love me mair.

Now Arthur's Seat shall be my bed, The sheets shall ne'er be fyled by me; Saint Anton's well shall be my drink, Since my true-love has forsaken me.

Martinmas wind, when wilt thou blaw And shake the green leaves off the tree? O gentle Death, when wilt thou come? For of my life I am weary.

'Tis not the frost that freezes fell, Nor blawing snaw's inclemency; 'Tis not sic cauld that makes me cry, But my love's heart grown cauld to me.

When we came in by Glasgow town, We were a comely sight to see; My love was clad in the black velvet, And I myself in cramasie.

But had I wist, before I kissed, That love had been sae ill to win, I'd locked my heart in a case of gold. And pinned it with a silver pin.

Oh, oh, if my young babe were born, And set upon the nurse's knee, And I myself were dead and gone, [And the green grass growing over me!]

The same ballad touch overweighs even the lyric quality of the verses about Yarrow:—

"Willy's rare, and Willy's fair, And Willy's wondrous bonny, And Willy heght[38] to marry me Gin e'er he married ony.

"Oh came you by yon water-side? Pu'd you the rose or lily? Or came you by yon meadow green? Or saw you my sweet Willy?"

She sought him east, she sought him west, She sought him brade and narrow; Syne, in the clifting of a craig, She found him drowned in Yarrow.[39]

Returning to Germany and to pure lyric, we have a pretty bit which is attached to many different songs.

High up on yonder mountain A mill-wheel clatters round, And, night or day, naught else but love Within the mill is ground.

The mill has gone to ruin, And love has had its day; God bless thee now, my bonnie lass, I wander far away.[40]

But there is a more cheerful vein in this sort of song; and the mountain offers pleasanter views:—

Oh yonder on the mountain, There stands a lofty house, Where morning after morning, Yes, morning, Three maids go in and out.[41]

The first she is my sister, The second well is known, The third, I will not name her, No, name her, And she shall be my own!

Finally, that pearl of German folk-song, 'Innsprück.' The wanderer must leave the town and his sweetheart; but he swears to be true, and prays that his love be kept safe till his return:—

Innsprück, I must forsake thee, My weary way betake me Unto a foreign shore, And all my joy hath vanished, And ne'er while I am banished Shall I behold it more.

I bear a load of sorrow, And comfort can I borrow, Dear love, from thee alone. Ah, let thy pity hover About thy weary lover When he is far from home.

My one true love! Forever Thine will I bide, and never Shall our dear vow be vain. Now must our Lord God ward thee, In peace and honor guard thee, Until I come again.

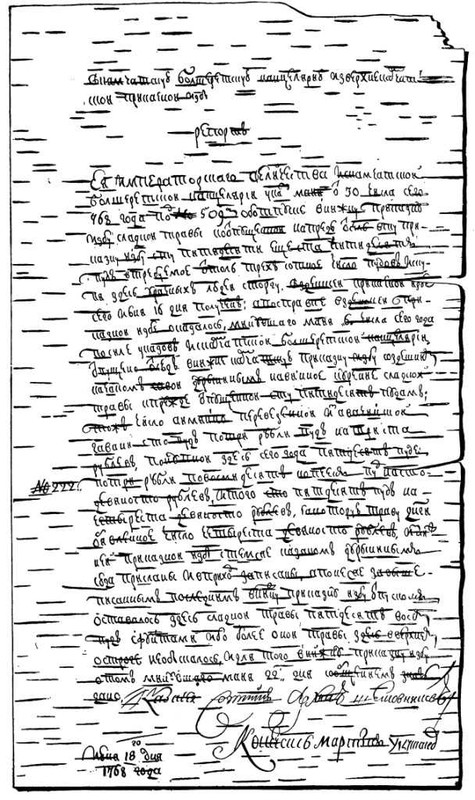

RUSSIAN CURSIVE WRITING. A public document of Kamtschatka, written on birch bark.

In leaving the subject of folk-song, it is necessary for the reader not only to consider anew the loose and unscientific way in which this term has been employed, but also to bear in mind that few of the above specimens can lay claim to the title in any rigid classification. Long ago, a German critic reminded zealous collectors of his day that when one has dipped a pailful of water from the brook, one has captured no brook; and that when one has written down a folk-song, it has ceased to be that eternally changing, momentary, spontaneous, dance-begotten thing which once flourished everywhere as communal poetry. Always in flux, if it stopped it ceased to be itself. Modern lyric is deliberately composed by some one, mainly to be sung by some one else; the old communal lyric was sung by the throng and was made in the singing. When festal excitement at some great communal rejoicing in the life of clan or tribe "fought its battles o'er again," the result was narrative communal song. A disguised and baffled survival of this most ancient narrative is the popular ballad. Still more disguised, still more baffled, is the purely lyrical survival of that old communal and festal song; and the best one can do is to present those few specimens found under conditions which preserve certain qualities of a vanished world of poetry.

It may be asked why the contemporary songs found among Indian tribes of our continent, or among remote islanders in low stages of culture, should not reproduce for us the old type of communal verse. The answer is simple. Tribes which have remained in low stages of culture do not necessarily retain all the characteristics of primitive life among races which had the germs of rapidly developing culture. That communal poetry which gave life to the later epic of Hellenic or of Germanic song must have differed materially, no matter in what stage of development, from the uninteresting and monotonous chants of the savage. Moreover, the specimens of savage verse which we know retain the characteristics of communal verse, while they lack its nobler and vital quality. The dance, the spontaneous production, repetition,—these are all marked characteristics of savage verse. But savage verse cannot serve as model for our ideas of primitive folk-song.

[1] For facsimile of the MS., music, and valuable remarks, see Chappell, 'Ballad Literature and Popular Music of the Olden Time,' Vol. i., frontispiece, and pages 21 ff. For pronunciation, see A. J. Ellis, 'Early English Pronunciation,' ii., 419 ff. The translation given by Mr. Ellis is:—

"Summer has come in; loudly sing, cuckoo! Grows seed and blossoms mead and springs the wood now. Sing, cuckoo! Ewe bleats after lamb, lows after (its) calf the cow; bullock leaps, buck verts (seeks the green); merrily sing, cuckoo! Cuckoo, cuckoo! Well singest thou, cuckoo; cease thou not never now. Burden.—Sing, cuckoo, now; sing, cuckoo! Sing, cuckoo, sing cuckoo, now."—Lhude, wde (=wude), awe, calve, bucke, are dissyllabic. Mr. Ellis's translation of verteth is very doubtful.

[2] The first stanza in the original will show the structure of this true "ballad" in the primitive sense of a dance-song. There are five of these stanzas, carrying the same rhymes throughout:—

A l'entrada del temps clar,—eya,—

Per joja recomençar,—eya,—

E per jelos irritar,—eya,—

Vol la regina mostrar

Qu' el' est si amoroza.

Refrain

Alavi', alavia, jelos,

laissaz nos, laissaz nos

ballar entre nos, entre nos!

[3] Games and songs of children are still to be found which preserve many of the features of these old dance-songs. The dramatic traits met with in the games point back now to the choral poetry of pagan times, when perhaps a bit of myth was enacted, now to the communal dance where the stealing of a bride may have been imitated.

[4] Unless otherwise credited, translations are by the writer.

[5] From 'Carmina Burana,' a collection of these songs in Latin and German preserved in a MS. of the thirteenth century; edited by J. A. Schmeller, Breslau, 1883. This song is page 181 ff., in German, 'Nu Suln Wir Alle Fröude Hân.'

[6] Ibid., page 178: 'Springe wir den Reigen.'

[7] Ibid., page 213: 'Ich wil Trûren Varen lân.'

[8] Article in 'Ballads,' Vol. iii., page 1340.

[9] Uhland, 'Volkslieder,' i. 12.

[10] Grundtvig, 'Danmarks Gamle Folkeviser,' iii. 161.

[11] We cannot widen our borders so as to include that solitary folk-song rescued from ancient Greek literature, the 'Song of the Swallow,' sung by children of the Island of Rhodes as they went about asking gifts from house to house at the coming of the earliest swallow. The metre is interesting in comparison with the rhythm of later European folk-songs, and there is evident dramatic action. Nor can we include the fragments of communal drama found in the favorite Debates Between Summer and Winter,—from the actual contest, to such lyrical forms as the song at the end of Shakespeare's 'Love's Labor's Lost.' The reader may be reminded of a good specimen of this class in 'Ivy and Holly,' printed by Ritson, 'Ancient Songs and Ballads,' Hazlitt's edition, page 114 ff., with the refrain:—

Nay, Ivy, nay,

Hyt shal not be, I wys;

Let Holy hafe the maystry,

As the maner ys.

[12] Folk-lore, mythology, sociology even, must share in this work. The reader may consult for indirect but valuable material such books as Frazer's 'Golden Bough,' or that admirable treatise, Tylor's 'Primitive Culture.'

[13] For early times translation from language to language is out of the question, certainly in the case of lyrics. It is very important to remember that primitive man regarded song as a momentary and spontaneous thing.

[14] Yet even rough Scandinavia took up this brilliant but doubtful love poetry. To one of the Norse kings is attributed a song in which the royal singer informs his "lady" by way of credentials for his wooing,—"I have struck a blow in the Saracen's land; let thy husband do the same!"

[15] 'Le Misanthrope,' i. 2; he calls it a vielle chanson. M. Tiersot concedes it to the popular muse, but thinks it is of the city, not of the country.

[16] May, a favorite ballad word for "maid," "sweetheart."

[17] 'Carm. Bur.,' page 185: "Wær diu werlt alliu mîn."

[18] See Child's Ballads, vi. 257, and Grandfer Cantle's ballad in Mr. Hardy's 'Return of the Native.' See next page.

[19] 'Carm. Bur.,' page 208: "Kume, Kume, geselle min."

[20] Translated from Böhme 'Altdeutsches Liederbuch,' Leipzig, 1877, page 233. Lovers of folk-song will find this book invaluable on account of the carefully edited musical accompaniments. With it and Chappell, the musician has ample material for English and German songs; for French, see Tiersot, 'La Chanson Populaire en France.'

[21] The garden in these later songs is constantly a symbol of love. To pluck the roses, etc., is conventional for making love.

[22] Quoted by Tiersot, page 88, from 'Chansons à Danser en Rond,' gathered before 1704.

[23] Böddeker's 'Old Poems from the Harleian MS. 2253,' with notes, etc., in German; Berlin, 1878, page 179.

[24] See also Ritson, 'Ancient Songs and Ballads,' 3rd Ed., pages xlviii., 202 ff. The Percy folio MS. preserved a cradle song, 'Balow, my Babe, ly Still and Sleepe,' which was published as a broadside, and finally came to be known as 'Lady Anne Bothwell's Lament.' These "balow" lullabies are said by Mr. Ebbsworth to be imitations of a pretty poem first published in 1593, and now printed by Mr. Bullen in his 'Songs from Elizabethan Romances,' page 92.

[25] Fere, companion, lover. "I would give all I have to be her lover."

[26] Superfluous verses; but the MS. makes no distinction. Free means noble, gracious. "If one could see everything between hell and heaven, one would find nothing so fair and noble."

[27] Lark. The poem is translated from Böddeker, page 161 ff.

[28] Traitor.

[29] Betray.

[30] The music in Chappell, page 141.

[31] Böhme, with music, page 94.

[32] Quoted by Child, 'Ballads,' iv. 318.

[33] Separated, divided.

[34] An equivalent to upside down, "in the wrong direction."

[35] See Tiersot, 'La Chanson Populaire,' p. 103, with the music. The final verses, simple as they are, are not rendered even remotely well. They run:—

Que je suis sa fidèle amie,

Et que vers lui je tends les bras.

[36] Tiersot, p. 90. In many versions there is further complication with king and queen and the lover. This song is extremely popular in Canada.

[37] Lightly (a verb) is to treat with contempt, to undervalue. Compare the burden quoted by Chappell, p. 458, and very old:—

The bonny broome, the well-favored broome,

The broome blooms faire on hill;

What ailed my love to lightly me,

And I working her will?

[38] Promised.

[39] Child's Ballads, vii. 179.

[40] Böhme, p. 271.

[41] The rhyme in German leaves even more to be desired.

SAMUEL FOOTE

(1720-1777)

he name of Samuel Foote suggests a whimsical, plump little man, with a round face, twinkling eyes, and one of the readiest wits of the eighteenth century. This contemporary of the elder Colman, Cumberland, Mrs. Cowley, and the great Garrick, knew many famous men and women, and they admired as well as feared his talents.

Samuel Foote was born at Truro in 1720. He was a young boy when he first exhibited his powers of mimicry at his father's dinner-table. At that time he did not expect to earn his living by them, for he came of well-to-do people, and his mother, who was of aristocratic birth, inherited a comfortable fortune.

Throughout his school days at Worcester and his college days at Worcester College, Oxford, where he did not remain long enough to take a degree, and the idle days when he was supposed to be studying law at the Temple and was in reality frequenting coffee-houses and drawing-rooms as a young man of fashion, he was establishing a reputation for repartee, bons mots, and satiric imitation. So, when the wasteful youth had squandered all his money, he naturally turned to the stage as offering him the best opportunity. Like many another amateur addicted to a mistaken ambition, Foote first tried tragedy, and made his début as Othello. But in this and in other tragedies he was a failure; so he soon took to writing comic plays with parts especially adapted to himself. 'The Diversions of the Morning' was the first of a long series, of which 'The Mayor of Garratt,' 'The Lame Lover,' 'The Nabob,' and 'The Minor,' are among the best known. As these were written from the actor's rather than from the dramatist's point of view, they often seem faulty in construction and crude in literary quality. They are farces rather than true comedies. But they abound in witty dialogue, and in a satire which illuminates contemporary vices and follies.

Foote seems to have been curiously lacking in conscience. He lived his life with a gayety which no poverty, misfortune, or physical suffering could long dampen. When he had money he spent it lavishly, and when the supply ran short he racked his clever brains to make a new hit. To accomplish this he was utterly unscrupulous, and never spared his friends or those to whom he was indebted, if he saw good material in their foibles. His victims smarted, but his ready tongue and personal geniality usually extricated him from consequent unpleasantness. Garrick, who aided him repeatedly, and who dreaded ridicule above all things, was his favorite butt, yet remained his friend. The irate members of the East India Company, who called upon him armed with stout cudgels to administer a castigation for an offensive libel in 'The Nabob,' were so speedily mollified that they laid their cudgels aside with their hats, and accepted his invitation to dinner.

To us, much of his charm has evaporated, for it lay in these very personalities which held well-known people up to ridicule with a precision which made it impossible for the originals to escape recognition. Even irascible Dr. Johnson, who wished to disapprove of him, admitted that there was no one like "that fellow Foote." So this "Aristophanes of the English stage" was mourned when he died at the age of fifty-seven, and a company of his friends and fellow-actors buried him one evening by the dim light of torches in a cloister of Westminster Abbey.

There is often a boisterous unreserve in the plays of Foote, as in other eighteenth-century drama, which revolts modern taste. As they consist of character study rather than incident, mere extracts are apt to appear incomplete and meaningless. Therefore it seems fairer to represent the famous wit not alone by formal citation, but also by some of his bons mots extracted from the collection of William Cooke in his 'Memoirs of Samuel Foote' (2 vols. 1806).

HOW TO BE A LAWYER

From 'The Lame Lover'

Enter Jack

Serjeant—So, Jack, anybody at chambers to-day?

Jack—Fieri Facias from Fetter Lane, about the bill to be filed by Kit Crape against Will Vizard this term.

Serjeant—Praying for an equal partition of plunder?

Jack—Yes, sir.

Serjeant—Strange world we live in, that even highwaymen can't be true to each other! [Half aside to himself.] But we shall make Vizard refund; we'll show him what long hands the law has.

Jack—Facias says that in all the books he can't hit a precedent.

Serjeant—Then I'll make one myself; Aut inveniam, aut faciam, has been always my motto. The charge must be made for partnership profit, by bartering lead and gunpowder against money, watches, and rings, on Epping Forest, Hounslow Heath, and other parts of the kingdom.

Jack—He says if the court should get scent of the scheme, the parties would all stand committed.

Serjeant—Cowardly rascal! but however, the caution mayn't prove amiss. [Aside.] I'll not put my own name to the bill.

Jack—The declaration, too, is delivered in the cause of Roger Rapp'em against Sir Solomon Simple.

Serjeant—What, the affair of the note?

Jack—Yes.

Serjeant—Why, he is clear that his client never gave such a note.

Jack—Defendant never saw plaintiff since the hour he was born; but notwithstanding, they have three witnesses to prove a consideration and signing the note.

Serjeant—They have!

Jack—He is puzzled what plea to put in.

Serjeant—Three witnesses ready, you say?

Jack—Yes.

Serjeant—Tell him Simple must acknowledge the note [Jack starts]; and bid him against the trial comes on, to procure four persons at least to prove the payment at the Crown and Anchor, the 10th of December.

Jack—But then how comes the note to remain in plaintiff's possession?

Serjeant—Well put, Jack: but we have a salvo for that; plaintiff happened not to have the note in his pocket, but promised to deliver it up when called thereunto by defendant.

Jack—That will do rarely.

Serjeant—Let the defense be a secret; for I see we have able people to deal with. But come, child, not to lose time, have you carefully conned those instructions I gave you?

Jack—Yes, sir.

Serjeant—Well, that we shall see. How many points are the great object of practice?

Jack—Two.

Serjeant—Which are they?

Jack—The first is to put a man into possession of what is his right.

Serjeant—The second?

Jack—Either to deprive a man of what is really his right, or to keep him as long as possible out of possession.

Serjeant—Good boy! To gain the last end, what are the best means to be used?

Jack—Various and many are the legal modes of delay.

Serjeant—Name them.

Jack—Injunctions, demurrers, sham pleas, writs of error, rejoinders, sur-rejoinders, rebutters, sur-rebutters, re-plications, exceptions, essoigns, and imparlance.

Serjeant [to himself]—Fine instruments in the hands of a man who knows how to use them. But now, Jack, we come to the point: if an able advocate has his choice in a cause, which if he is in reputation he may readily have, which side should he choose, the right or the wrong?

Jack—A great lawyer's business is always to make choice of the wrong.

Serjeant—And prithee, why so?

Jack—Because a good cause can speak for itself, whilst a bad one demands an able counselor to give it a color.

Serjeant—Very well. But in what respects will this answer to the lawyer himself?

Jack—In a twofold way. Firstly, his fees will be large in proportion to the dirty work he is to do.

Serjeant—Secondly?

Jack—His reputation will rise, by obtaining the victory in a desperate cause.

Serjeant—Right, boy. Are you ready in the case of the cow?

Jack—Pretty well, I believe.

Serjeant—Give it, then.

Jack—First of April, anno seventeen hundred and blank, John a-Nokes was indicted by blank, before blank, in the county of blank, for stealing a cow, contra pacem, etc., and against the statute in that case provided and made, to prevent stealing of cattle.

Serjeant—Go on.

Jack—Said Nokes was convicted upon the said statute.

Serjeant—What followed upon?

Jack—Motion in arrest of judgment, made by Counselor Puzzle. First, because the field from whence the cow was conveyed is laid in the indictment as round, but turned out upon proof to be square.

Serjeant—That's well. A valid objection.

Jack—Secondly, because in said indictment the color of the cow is called red; there being no such things in rerum natura as red cows, no more than black lions, spread eagles, flying griffins, or blue boars.

Serjeant—Well put.

Jack—Thirdly, said Nokes has not offended against form of the statute; because stealing of cattle is there provided against: whereas we are only convicted of stealing a cow. Now, though cattle may be cows, yet it does by no means follow that cows must be cattle.

Serjeant—Bravo, bravo! buss me, you rogue; you are your father's own son! go on and prosper. I am sorry, dear Jack, I must leave thee. If Providence but sends thee life and health, I prophesy thou wilt wrest as much land from the owners, and save as many thieves from the gallows, as any practitioner since the days of King Alfred.

Jack—I'll do my endeavor. [Exit Serjeant.]

A MISFORTUNE IN ORTHOGRAPHY

From 'The Lame Lover'

Sir Luke—A pox o' your law; you make me lose sight of my story. One morning a Welsh coach-maker came with his bill to my lord, whose name was unluckily Lloyd. My lord had the man up: "You are called, I think, Mr. Lloyd?"—"At your Lordship's service, my lord."—"What, Lloyd with an L?"—"It was with an L indeed, my lord."—"Because in your part of the world I have heard that Lloyd and Floyd were synonymous, the very same names."—"Very often indeed, my Lord."—"But you always spell yours with an L?"—"Always."—"That, Mr. Lloyd, is a little unlucky; for you must know I am now paying my debts alphabetically, and in four or five years you might have come in with an F; but I am afraid I can give you no hopes for your L. Ha, ha, ha!"

FROM THE 'MEMOIRS'

A Cure for Bad Poetry

A physician of Bath told him that he had a mind to publish his own poems; but he had so many irons in the fire he did not well know what to do.

"Then take my advice, doctor," said Foote, "and put your poems where your irons are."

The Retort Courteous

Following a man in the street, who did not bear the best of characters, Foote slapped him familiarly on the shoulder, thinking he was an intimate friend. On discovering his mistake he cried out, "Oh, sir, I beg your pardon! I really took you for a gentleman who—"

"Well, sir," said the other, "and am I not a gentleman?"

"Nay, sir," said Foote, "if you take it in that way, I must only beg your pardon a second time."

On Garrick's Stature

Previously to Foote's bringing out his 'Primitive Puppet Show' at the Haymarket Theatre, a lady of fashion asked him, "Pray, sir, are your puppets to be as large as life?"

"Oh dear, madam, no. Not much above the size of Garrick!"

Cape Wine

Being at the dinner-table one day when the Cape was going round in remarkably small glasses, his host was very profuse on the excellence of the wine, its age, etc. "But you don't seem to relish it, Foote, by keeping your glass so long before you."

"Oh, yes, my lord, perfectly well. I am only admiring how little it is, considering its great age."

The Graces

Of an actress who was remarkably awkward with her arms, Foote said that "she kept the Graces at arm's-length."

The Debtor

Of a young gentleman who was rather backward in paying his debts, he said he was "a very promising young gentleman."

Affectation

An assuming, pedantic lady, boasting of the many books which she had read, often quoted 'Locke Upon Understanding,' a work she said she admired above all things, yet there was one word in it which, though often repeated, she could not distinctly make out; and that was the word ide-a (pronouncing it very long): "but I suppose it comes from a Greek derivation."

"You are perfectly right, madam," said Foote, "it comes from the word ideaousky."

"And pray, sir, what does that mean?"

"The feminine of idiot, madam."

Arithmetical Criticism

A mercantile man of his acquaintance, who would read a poem of his to him one day after dinner, pompously began:—

[30] The music in Chappell, page 141.

[31] Böhme, with music, page 94.

[32] Quoted by Child, 'Ballads,' iv. 318.

[33] Separated, divided.

[34] An equivalent to upside down, "in the wrong direction."

[35] See Tiersot, 'La Chanson Populaire,' p. 103, with the music. The final verses, simple as they are, are not rendered even remotely well. They run:—

[36] Tiersot, p. 90. In many versions there is further complication with king and queen and the lover. This song is extremely popular in Canada.

[37] Lightly (a verb) is to treat with contempt, to undervalue. Compare the burden quoted by Chappell, p. 458, and very old:—

[38] Promised.

[39] Child's Ballads, vii. 179.

[40] Böhme, p. 271.

[41] The rhyme in German leaves even more to be desired.

Sing cuccu. Sing cuccu nu.[1]