автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Library of the World's Best Literature, Ancient and Modern — Volume 6

LIBRARY OF THE

WORLD'S BEST LITERATURE

ANCIENT AND MODERN

CHARLES DUDLEY WARNER

EDITOR

HAMILTON WRIGHT MABIE

LUCIA GILBERT RUNKLE

GEORGE HENRY WARNER

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Connoisseur Edition

VOL. VI.

1896

THE ADVISORY COUNCIL

CRAWFORD H. TOY, A.M., LL.D.,

Professor of Hebrew,

HARVARD UNIVERSITY, Cambridge, Mass.

THOMAS R. LOUNSBURY, LL.D., L.H.D.,

Professor of English in the Sheffield Scientific School of

YALE UNIVERSITY, New Haven, Conn.

WILLIAM M. SLOANE, PH.D., L.H.D.,

Professor of History and Political Science,

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY, Princeton, N.J.

BRANDER MATTHEWS, A.M., LL.B.,

Professor of Literature,

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, New York City.

JAMES B. ANGELL, LL.D.,

President of the

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, Ann Arbor, Mich.

WILLARD FISKE, A.M., PH.D.,

Late Professor of the Germanic and Scandinavian Languages and Literatures,

CORNELL UNIVERSITY, Ithaca, N.Y.

EDWARD S. HOLDEN, A.M., LL.D.,

Director of the Lick Observatory, and Astronomer

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, Berkeley, Cal.

ALCÉE FORTIER, LIT.D.,

Professor of the Romance Languages,

TULANE UNIVERSITY, New Orleans, La.

WILLIAM P. TRENT, M.A.,

Dean of the Department of Arts and Sciences, and Professor of English and History,

UNIVERSITY OF THE SOUTH, Sewanee, Tenn.

PAUL SHOREY, PH.D.,

Professor of Greek and Latin Literature,

UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO, Chicago, Ill.

WILLIAM T. HARRIS, LL.D.,

United States Commissioner of Education,

BUREAU OF EDUCATION, Washington, D.C.

MAURICE FRANCIS EGAN, A.M., LL.D.,

Professor of Literature in the

CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA, Washington, D.C.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

VOL. VI

THE ABBÉ DE BRANTÔME (Pierre de Bourdeille) -- 1527-1614

The Dancing of Royalty ('Lives of Notable Women')

The Shadow of a Tomb ('Lives of Courtly Women')

M. le Constable Anne de Montmorency

('Lives of Distinguished Men and Great Captains')

Two Famous Entertainments ('Lives of Courtly Women')

FREDRIKA BREMER -- 1801-1865

A Home-Coming ('The Neighbors')

The Landed Proprietor ('The Home')

A Family Picture (same)

CLEMENS BRENTANO -- 1778-1842

The Nurse's Watch

The Castle in Austria

ELISABETH BRENTANO (Bettina von Arnim) -- 1785-1859

Dedication: To Goethe ('Goethe's Correspondence with a Child')

Letter to Goethe

Bettina's Last Meeting with Goethe (Letter to Her Niece)

In Goethe's Garden

JOHN BRIGHT -- 1811-1889

From Speech on the Corn Laws (1843)

From Speech on Incendiarism in Ireland (1844)

From Speech on Non-Recognition of the Southern Confederacy (1861)

From Speech on the State of Ireland (1866)

From Speech on the Irish Established Church (1868)

BRILLAT-SAVARIN -- 1755-1826

From 'Physiology of Taste':

The Privations;

On the Love of Good Living;

On People Fond of Good Living

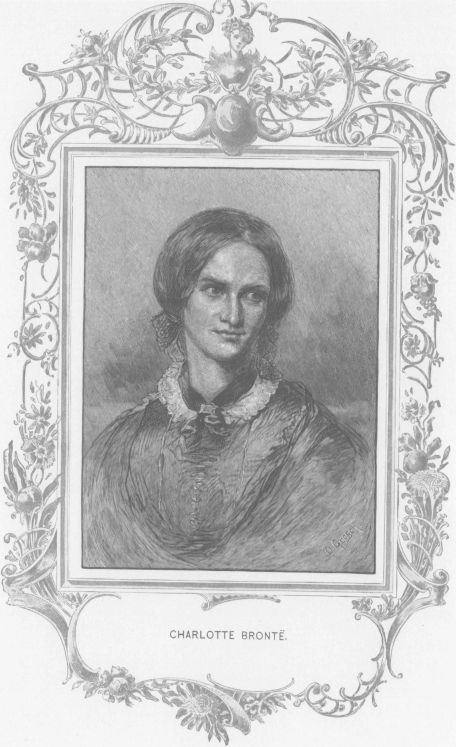

CHARLOTTE BRONTÉ AND HER SISTERS --1816-1855

Jane Eyre's Wedding-Day ('Jane Eyre')

Madame Beck ('Villette')

A Yorkshire Landscape ('Shirley')

The End of Heathcliff (Emily Bronté's 'Wuthering Heights')

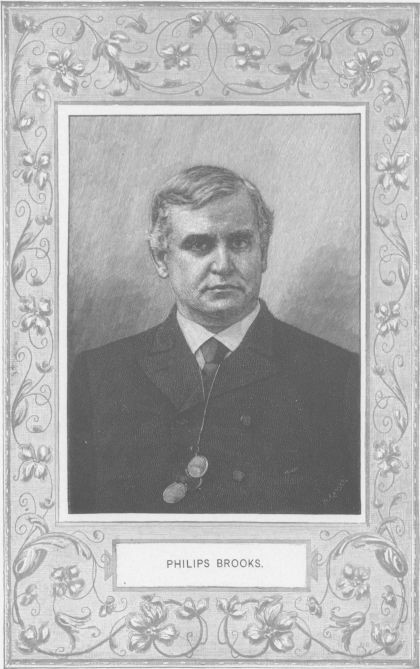

PHILLIPS BROOKS -- 1835-1893

O Little Town of Bethlehem

Personal Character ('Essays and Addresses')

The Courage of Opinions (same)

Literature and Life (same)

CHARLES BROCKDEN BROWN -- 1771-1810

Wieland's Statement ('Wieland')

JOHN BROWN -- 1810-1882

Marjorie Fleming ('Spare Hours')

Death of Thackeray (same)

CHARLES FARRAR BROWNE (Artemus Ward) -- 1834-1867

By Charles F. Johnson

Edwin Forrest as Othello

High-Handed Outrage at Utica

Affairs Round the Village Green

Mr. Pepper ('Artemus Ward: His Travels')

Horace Greeley's Ride to Placerville (same)

SIR THOMAS BROWNE -- 1605-1682

By Francis Bacon

From the 'Religio Medici'

From 'Christian Morals'

From 'Hydriotaphia, or Urn-Burial'

From 'A Fragment on Mummies'

From 'A Letter to a Friend'

Some Relations Whose Truth We Fear ('Pseudoxia Epidemica')

WILLIAM BROWNE -- 1591-1643

Circe's Charm ('Inner Temple Masque')

The Hunted Squirrel ('Britannia's Pastorals')

As Careful Merchants Do Expecting Stand (same)

Song of the Sirens ('Inner Temple Masque')

An Epistle on Parting

Sonnets to Cælia

HENRY HOWARD BROWNELL -- 1820-1872

Annus Memorabilis

Words for the 'Hallelujah Chorus'

Coming

Psychaura

Suspiria Noctis

ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING -- 1809-1861

A Musical Instrument

My Heart and I

From 'Catarina to Camoens'

The Sleep

The Cry of the Children

Mother and Poet

A Court Lady

The Prospect

De Profundis

The Cry of the Human

Romance of the Swan's Nest

The Best Thing in the World

Sonnets from the Portuguese

A False Step

A Child's Thought of God

Cheerfulness Taught by Reason

ROBERT BROWNING -- 1812-1889

By E.L. Burlingame

Andrea del Sarto

A Toccata of Galuppi's

Confessions

Love among the Ruins

A Grammarian's Funeral

My Last Duchess

Up at a Villa--Down in the City

In Three Days

In a Year

Evelyn Hope

Prospice

The Patriot

One Word More

ORESTES AUGUSTUS BROWNSON -- 1803-1876

Saint-Simonism ('The Convert')

FERDINAND BRUNETIÈRE -- 1849-

By Adolphe Cohn

Taine and Prince Napoleon

The Literatures of France, England, and Germany

GIORDANO BRUNO --1548-1600

A Discourse of Poets ('The Heroic Enthusiasts')

Canticle of the Shining Ones: A Tribute to English Women ('The Nolan')

Song of the Nine Singers

Of Immensity

Life Well Lost

Parnassus Within

Compensation

Life for Song

WILLIAM CULLEN BRYANT --1794-1878

By George Parsons Lathrop

Thanatopsis

The Crowded Street

Death of the Flowers

The Conqueror's Grave

The Battle-Field

To a Water-fowl

Robert of Lincoln

June

To the Fringed Gentian

The Future Life

To the Past

JAMES BRYCE -- 1838-

Position of Women in the United States ('The American Commonwealth')

Ascent of Ararat ('Trans-Caucasia and Ararat')

The Work of the Roman Empire ('The Holy Roman Empire')

FRANCIS TREVELYAN BUCKLAND -- 1826-1880

A Hunt in a Horse-Pond ('Curiosities of Natural History')

On Rats (same)

Snakes and their Poison (same)

My Monkey Jacko (same)

HENRY THOMAS BUCKLE -- 1821-1862

Moral versus Intellectual Principles in Human Progress

('History of Civilization in England')

Mythical Origin of History (same)

GEORGE LOUIS LE CLERC BUFFON -- 1707-1788

By Spencer Trotter

Nature ('Natural History')

The Humming-Bird (same)

EDWARD BULWER-LYTTON -- 1803-1873

By Julian Hawthorne

The Amphitheatre ('The Last Days of Pompeii')

Kenelm and Lily ('Kenelm Chillingly')

FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

VOLUME VI

"Les Satyres"(Colored Plate)

Frontispiece Charlotte Bronté(Portrait)

2382 Phillips Brooks(Portrait)

2418 "The Holy Child of Bethlehem"(Photogravure)

2420 "Circe"(Photogravure)

2514 Robert Browning(Portrait)

2558 William Cullen Bryant(Portrait)

2624 Edward Bulwer-Lytton(Portrait)

2698 "In the Arena"(Photogravure)

2718 "Nydia"(Photogravure)

2720

VIGNETTE PORTRAITS

Abbé de Brantôme

Fredrika Bremer

Elisabeth Brentano

John Bright

Brillat-Savarin

Charles Brockden Brown

John Brown

Charles Farrar Browne

Sir Thomas Browne

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Orestes Augustus Brownson

Ferdinand Brunetière

James Bryce

George Louis le Clere Buffon

THE ABBÉ DE BRANTÔME (PIERRE DE BOURDEILLE)

(1527-1614)

very historian of the Valois period is indebted to Brantôme for preserving the atmosphere and detail of the brilliant life in which he moved as a dashing courtier, a military adventurer, and a gallant gentleman of high degree. He was not a professional scribe, nor a student; but he took notes unconsciously, and in the evening of his life turned back the pages of his memory to record the scenes through which he had passed and the characters which he had known. He has been termed the "valet de chambre" of history; nevertheless the anecdotes scattered through his works will ever be treasured by all students and historians of that age of luxury and magnificence, art and beauty, beneath which lay the fermentation of great religious and political movements, culminating in the struggle between the Huguenots and Catholics.

Abbé De Brantôme

Brantôme was the third son of the Vicomte de Bourdeille, a Périgord nobleman, whose family had lived long in Guienne, and whose aristocratic lineage was lost in myth. Upon the estate stood the Abbey of Brantôme, founded by Charlemagne, and this Henry II. gave to young Pierre de Bourdeille in recognition of the military deeds of his brother, Jean de Bourdeille, who lost his life in service. Thereafter the lad was to sign his name as the Reverend Father in God, Messire Pierre de Bourdeille, Abbé de Brantôme. Born in the old château in 1527, he was destined for the church, but abandoned this career for arms. At an early age he was sent to court as page to Marguerite, sister of Francis I. and Queen of Navarre; after her death in 1549, he went to Paris to study at the University. His title of Abbé being merely honorary, he served in the army under François de Guise, Duke of Lorraine, and became Gentleman of the Chamber to Charles IX. His career extended through the reigns of Henry II., Francis II., Charles IX., Henry III., and Henry IV., to that of Louis XIII. With the exception of diplomatic missions, service on the battle-field, and voyages for pleasure, he spent his life at court.

About 1594 he retired to his estate, where until his death on July 15th, 1614, he passed his days in contentions with the monks of Brantôme, in lawsuits with his neighbors, and in writing his books: 'Lives of the Illustrious Men and Great Captains of France'; 'Lives of Illustrious Ladies'; 'Lives of Women of Gallantry'; 'Memoirs, containing anecdotes connected with the Court of France'; 'Spanish Rodomontades'; a 'Life' of his father, François de Bourdeille; a 'Funeral Oration' on his sister in-law; and a dialogue in verse, entitled 'The Tomb of Madame de Bourdeille.' These were not published until long after his death, first appearing in Leyden about 1665, at the Hague in 1740, and in Paris in 1787. The best editions are by Fourcault (7 vols., Paris, 1822); by Lacour and Mérimée (3 vols., 1859); and Lalande (10 vols., 1865-'81).

What Brantôme thought of himself may be seen by glancing at that portion of the "testament mystique" which relates to his writings:--

"I will and expressly charge my heirs that they cause to be printed the books which I have composed by my talent and invention. These books will be found covered with velvet, either black, green or blue, and one larger volume, which is that of the Rodomontades, covered with velvet, gilt outside and curiously bound. All have been carefully corrected. There will be found in these books excellent things, such as stories, histories, discourses, and witty sayings, which I flatter myself the world will not disdain to read when once it has had a sight of them. I direct that a sum of money be taken from my estate sufficient to pay for the printing thereof, which certainly cannot be much; for I have known many printers who would have given money rather than charged any for the right of printing them. They print many things without charge which are not at all equal to mine. I will also that the said impression shall be in large type, in order to make the better appearance, and that they should appear with the Royal Privilege, which the King will readily grant. Also care must be taken that the printers do not put on the title-page any supposititious name instead of mine. Otherwise, I should be defrauded of the glory which is my due."

The old man delighted in complimenting himself and talking about his "grandeur d'âme." This greatness of soul may be measured from the command he gave his heirs to annoy a man who had refused to swear homage to him, "it not being reasonable to leave at rest this little wretch, who descends from a low family, and whose grandfather was nothing but a notary." He also commands his nieces and nephews to take the same vengeance upon his enemies "as I should have done in my green and vigorous youth, during which I may boast, and I thank God for it, that I never received an injury without being revenged on the author of it."

Brantôme writes like a "gentleman of the sword," with dash and élan, and as one, to use his own words, who has been "toujours trottant, traversant, et vagabondant le monde" (always trotting, traversing, and tramping the world). Not in the habit of a vagabond, however, for the balls, banquets, tournaments, masques, ballets, and wedding-feasts which he describes so vividly were occasions for the display of sumptuous costumes; and Messire Pierre de Bourdeille doubtless appeared as elegant as any other gallant in silken hose, jeweled doublet, flowing cape, and long rapier. What we value most are his paintings of these festive scenes, and the vivid portraits which he has left of the Valois women, who were largely responsible for the luxuries and the crimes of the period: women who could step without a tremor from a court-masque to a massacre; who could toy with a gallant's ribbons and direct the blow of an assassin; and who could poison a rival with a delicately perfumed gift. Such a court Brantôme calls the "true paradise of the world, school of all honesty and virtue, ornament of France." We like to hear about Catherine de' Medici riding with her famous "squadron of Venus": "You should have seen forty or fifty dames and demoiselles following her, mounted on beautifully accoutred hackneys, their hats adorned with feathers which increased their charm, so well did the flying plumes represent the demand for love or war. Virgil, who undertook to describe the fine apparel of Queen Dido when she went out hunting, has by no means equaled that of our Queen and her ladies."

Charming, too, are such descriptions as "the most beautiful ballet that ever was, composed of sixteen of the fairest and best-trained dames and demoiselles, who appeared in a silvered rock where they were seated in niches, shut in on every side. The sixteen ladies represented the sixteen provinces of France. After having made the round of the hall for parade as in a camp, they all descended, and ranging themselves in the form of a little oddly contrived battalion, some thirty violins began a very pleasant warlike air, to which they danced their ballet." After an hour the ladies presented the King, the Queen-Mother, and others with golden plaques, on which were engraved "the fruits and singularities of each province," the wheat of Champagne, the vines of Burgundy, the lemons and oranges of Provence, etc. He shows us Catherine de' Medici, the elegant, cunning Florentine; her beautiful daughters, Elizabeth of Spain and Marguerite de Valois; Diana of Poitiers, the woman of eternal youth and beauty; Jeanne d'Albret, the mother of Henry IV.; Louise de Vaudemont; the Duchesse d'Étampes; Marie Touchet; and all their satellites,--as they enjoyed their lives.

Very valuable are the data regarding Mary Stuart's departure from France in 1561. Brantôme was one of her suite, and describes her grief when the shores of France faded away, and her arrival in Scotland, where on the first night she was serenaded by Psalm-tunes with a most villainous accompaniment of Scotch music. "Hé! quelle musique!" he exclaims, "et quel repos pour la nuit!"

But of all the gay ladies Brantôme loves to dwell upon, his favorites are the two Marguerites: Marguerite of Angoulême, Queen of Navarre, the sister of Francis I., and Marguerite, daughter of Catherine de' Medici and wife of Henry IV. Of the latter, called familiarly "La Reine Margot," he is always writing. "To speak of the beauty of this rare princess," he says, "I think that all that are, or will be, or have ever been near her are ugly."

Brantôme has been a puzzle to many critics, who cannot explain his "contradictions." He had none. He extolled wicked and immoral characters because he recognized only two merits,--aristocratic birth and hatred of the Huguenots. He is well described by M. de Barante, who says:--"Brantôme expresses the entire character of his country and of his profession. Careless of the difference between good and evil; a courtier who has no idea that anything can be blameworthy in the great, but who sees and narrates their vices and their crimes all the more frankly in that he is not very sure whether what he tells be good or bad; as indifferent to the honor of women as he is to the morality of men; relating scandalous things with no consciousness that they are such, and almost leading his reader into accepting them as the simplest things in the world, so little importance does he attach to them; terming Louis XI., who poisoned his brother, the good King Louis, calling women whose adventures could hardly have been written by any pen save his own, honnêtes dames."

Brantôme must therefore not be regarded as a chronicler who revels in scandals, although his pages reek with them; but as the true mirror of the Valois court and the Valois period.

THE DANCING OF ROYALTY

From 'Lives of Notable Women'

Ah! how the times have changed since I saw them together in the ball-room, expressing the very spirit of the dance! The King always opened the grand ball by leading out his sister, and each equaled the other in majesty and grace. I have often seen them dancing the Pavane d'Espagne, which must be performed with the utmost majesty and grace. The eyes of the entire court were riveted upon them, ravished by this lovely scene; for the measures were so well danced, the steps so intelligently placed, the sudden pauses timed so accurately and making so elegant an effect, that one did not know what to admire most,--the beautiful manner of moving, or the majesty of the halts, now expressing excessive gayety, now a beautiful and haughty disdain. Who could dance with such elegance and grace as the royal brother and sister? None, I believe; and I have watched the King dancing with the Queen of Spain and the Queen of Scotland, each of whom was an excellent dancer.

I have seen them dance the 'Pazzemezzo d'Italie,' walking gravely through the measures, and directing their steps with so graceful and solemn a manner that no other prince nor lady could approach them in dignity. This Queen took great pleasure in performing these grave dances; for she preferred to exhibit dignified grace rather than to express the gayety of the Branle, the Volta, and the Courante. Although she acquired them quickly, she did not think them worthy of her majesty.

I always enjoyed seeing her dance the Branle de la Torche, or du Flambeau. Once, returning from the nuptials of the daughter of the King of Poland, I saw her dance this kind of a Branle at Lyons before the assembled guests from Savoy, Piedmont, Italy, and other places; and every one said he had never seen any sight more captivating than this lovely lady moving with grace of motion and majestic mien, all agreeing that she had no need of the flaming torch which she held in her hand; for the flashing light from her brilliant eyes was sufficient to illuminate the set, and to pierce the dark veil of Night.

THE SHADOW OF A TOMB

From 'Lives of Courtly Women'

Once I had an elder brother who was called Captain Bourdeille, one of the bravest and most valiant soldiers of his time. Although he was my brother, I must praise him, for the record he made in the wars brought him fame. He was the gentilhomme de France who stood first in the science and gallantry of arms. He was killed during the last siege of Hesdin. My brother's parents had destined him for the career of letters, and accordingly sent him at the age of eighteen to study in Italy, where he settled in Ferrara because of Madame Renée de France, Duchess of Ferrara, who ardently loved my mother. He enjoyed life at her court, and soon fell deeply in love with a young French widow,--Mademoiselle de La Roche,--who was in the suite of Madame de Ferrara.

They remained there in the service of love, until my father, seeing that his son was not following literature, ordered him home. She, who loved him, begged him to take her with him to France and to the court of Marguerite of Navarre, whom she had served, and who had given her to Madame Renée when she went to Italy upon her marriage. My brother, who was young, was greatly charmed to have her companionship, and conducted her to Pau. The Queen was glad to welcome her, for the young widow was handsome and accomplished, and indeed considered superior in esprit to the other ladies of the court.

After remaining a few days with my mother and grandmother, who were there, my brother visited his father. In a short time he declared that he was disgusted with letters, and joined the army, serving in the wars of Piedmont and Parma, where he acquired much honor in the space of five or six months; during which time he did not revisit his home. At the end of this period he went to see his mother at Pau. He made his reverence to the Queen of Navarre as she returned from vespers; and she, who was the best princess in the world, received him cordially, and taking his hand, led him about the church for an hour or two. She demanded news regarding the wars of Piedmont and Italy, and many other particulars, to which my brother replied so well that she was greatly pleased with him. He was a very handsome young man of twenty-four years. After talking gravely and engaging him in earnest conversation, walking up and down the church, she directed her steps toward the tomb of Mademoiselle de La Roche, who had been dead for three months. She stopped here, and again took his hand, saying, "My cousin" (thus addressing him because a daughter of D'Albret was married into our family of Bourdeille; but of this I do not boast, for it has not helped me particularly), "do you not feel something move below your feet?"

"No, Madame," he replied.

"But reflect again, my cousin," she insisted.

My brother answered, "Madame, I feel nothing move. I stand upon a solid stone."

"Then I will explain," said the Queen, "without keeping you longer in suspense, that you stand upon the tomb and over the body of your poor dearly-loved Mademoiselle de La Roche, who is interred here; and that our friends may have sentiment for us at our death, render a pious homage here. You cannot doubt that the gentle creature, dying so recently, must have been affected when you approached. In remembrance I beg you to say a paternoster and an Ave Maria and a de profundis, and sprinkle holy water. Thus you will win the name of a very faithful lover and a good Christian."

M. LE CONSTABLE ANNE DE MONTMORENCY

From 'Lives of Distinguished Men and Great Captains'

He never failed to say and keep up his paternosters every morning, whether he remained in the house, or mounted his horse and went out to the field to join the army. It was a common saying among the soldiers that one must "beware the paternosters of the Constable." For as disorders were very frequent, he would say, while mumbling and muttering his paternosters all the time, "Go and fetch that fellow and hang me him up to this tree;" "Out with a file of harquebusiers here before me this instant, for the execution of this man!" "Burn me this village instantly!" "Cut me to pieces at once all these villain peasants, who have dared to hold this church against the king!" All this without ever ceasing from his paternosters till he had finished them--thinking that he would have done very wrong to put them off to another time; so conscientious was he!

TWO FAMOUS ENTERTAINMENTS

From 'Lives of Courtly Women'

I have read in a Spanish book called 'El Viaje del Principe' (The Voyage of the Prince), made by the King of Spain in the Pays-Bas in the time of the Emperor Charles, his father, about the wonderful entertainments given in the rich cities. The most famous was that of the Queen of Hungary in the lovely town of Bains, which passed into a proverb, "Mas bravas que las festas de Bains" (more magnificent than the festivals of Bains). Among the displays which were seen during the siege of a counterfeit castle, she ordered for one day a fête in honor of the Emperor her brother, Queen Eleanor her sister, and the gentlemen and ladies of the court.

Toward the end of the feast a lady appeared with six Oread-nymphs, dressed as huntresses in classic costumes of silver and green, glittering with jewels to imitate the light of the moon. Each one carried a bow and arrows in her hand and wore a quiver on her shoulder; their buskins were of cloth of silver. They entered the hall, leading their dogs after them, and placed on the table in front of the Emperor all kinds of venison pasties, supposed to have been the spoils of the chase. After them came the Goddess of Shepherds and her six nymphs, dressed in cloth of silver, garnished with pearls. They wore knee-breeches beneath their flowing robes, and white pumps, and brought in various products of the dairy.

Then entered the third division--Pomona and her nymphs--bearing fruit of all descriptions. This goddess was the daughter of Donna Beatrix Pacheco, Countess d'Autremont, lady-in-waiting to Queen Eleanor, and was but nine years old. She was now Madame l'Admirale de Chastillon, whom the Admiral married for his second wife. Approaching with her companions, she presented her gifts to the Emperor with an eloquent speech, delivered so beautifully that she received the admiration of the entire assembly, and all predicted that she would become a beautiful, charming, graceful, and captivating lady. She was dressed in cloth of silver and white, with white buskins, and a profusion of precious stones--emeralds, colored like some of the fruit she bore. After making these presentations, she gave the Emperor a Palm of Victory, made of green enamel, the fronds tipped with pearls and jewels. This was very rich and gorgeous. To Queen Eleanor she gave a fan containing a mirror set with gems of great value. Indeed, the Queen of Hungary showed that she was a very excellent lady, and the Emperor was proud of a sister worthy of himself. All the young ladies who impersonated these mythical characters were selected from the suites of France, Hungary, and Madame de Lorraine; and were therefore French, Italian, Flemish, German, and of Lorraine. None of them lacked beauty.

At the same time that these fêtes were taking place at Bains, Henry II. made his entrée in Piedmont and at his garrisons in Lyons, where were assembled the most brilliant of his courtiers and court ladies. If the representation of Diana and her chase given by the Queen of Hungary was found beautiful, the one at Lyons was more beautiful and complete. As the king entered the city, he saw obelisks of antiquity to the right and left, and a wall of six feet was constructed along the road to the courtyard, which was filled with underbrush and planted thickly with trees and shrubbery. In this miniature forest were hidden deer and other animals.

As soon as his Majesty approached, to the sound of horns and trumpets Diana issued forth with her companions, dressed in the fashion of a classic nymph with her quiver at her side and her bow in her hand. Her figure was draped in black and gold sprinkled with silver stars, the sleeves were of crimson satin bordered with gold, and the garment, looped up above the knee, revealed her buskins of crimson satin covered with pearls and embroidery. Her hair was entwined with magnificent strings of rich pearls and gems of much value, and above her brow was placed a crescent of silver, surrounded by little diamonds. Gold could never have suggested half so well as the shining silver the white light of the real crescent. Her companions were attired in classic costumes made of taffetas of various colors, shot with gold, and their ringlets were adorned with all kinds of glittering gems....

Other nymphs carried darts of Brazil-wood tipped with black and white tassels, and carried horns and trumpets suspended by ribbons of white and black. When the King appeared, a lion, which had long been under training, ran from the wood and lay at the feet of the Goddess, who bound him with a leash of white and black and led him to the king, accompanying her action with a poem of ten verses, which she delivered most beautifully. Like the lion--so ran the lines--the city of Lyons lay at his Majesty's feet, gentle, gracious, and obedient to his command. This spoken, Diana and her nymphs made low bows and retired.

Note that Diana and her companions were married women, widows, and young girls, taken from the best society in Lyons, and there was no fault to be found with the way they performed their parts. The King, the princes, and the ladies and gentlemen of the court were ravished. Madame de Valentinois, called Diana of Poitiers,--whom the King served and in whose name the mock chase was arranged,--was not less content.

FREDRIKA BREMER

(1801-1865)

redrika Bremer was born at Tuorla Manor-house, near Åbo, in Finland, on the 17th of August, 1801. In 1804 the family removed to Stockholm, and two years later to a large estate at Årsta, some twenty miles from the capital, which was her subsequent home. At Årsta the father of Fredrika, who had amassed a fortune in the iron industry in Finland, set up an establishment in accord with his means. The manor-house, built two centuries before, had become in some parts dilapidated, but it was ultimately restored and improved beyond its original condition. From its windows on one side the eye stretched over nearly five miles of meadows, fields, and villages belonging to the estate.

Fredrika Bremer

In spite of its surroundings, however, Fredrika's childhood was not a happy one. Her mother was severe and impatient of petty faults, and the child's mind became embittered. Her father was reserved and melancholy. Fredrika herself was restless and passionate, although of an affectionate nature. Among the other children she was the ugly duckling, who was misunderstood, and whose natural development was continually checked and frustrated. Her talents were early exhibited in a variety of directions. Her first verses, in French, to the morn, were written at the age of eight. Subsequently she wrote comedies for home production, prose and verse of all sorts, and kept a journal, which has been preserved. In 1821 the whole family went on a tour abroad, from which they did not return until the following year, having visited in the meantime Germany, Switzerland, and France, and spent the winter in Paris. This year among new scenes and surroundings seems to have brought home to Fredrika, upon the resumption of her old life in the country, its narrowness and its isolation. She was entirely shut off from all desired activity; her illusions vanished one by one. "I was conscious," she says in her short autobiography, "of being born with powerful wings, but I was conscious of their being clipped;" and she fancied that they would remain so.

Her attention, however, was fortunately attracted from herself to the poor and sick in the country round about; and she presently became to the whole region a nurse and a helper, denying herself all sorts of comforts that she might give them to others, and braving storm and hunger on her errands of mercy. In order to earn money for her charities she painted miniature portraits of the Crown Princess and the King, and secretly sold them. Her desire to increase the small sums she thus gained induced her to seek a publisher for a number of sketches she had written. Her brother readily disposed of the manuscript for a hundred rix-dollars; and her first book, 'Teckningar ur Hvardagslifvet' (Sketches of Every-day Life), appeared in 1828, but without the name of the author, of whose identity the publisher himself was left in ignorance. The book was received with such favor that the young author was induced to try again; and what had originally been intended as a second volume of the 'Sketches' appeared in 1830 as 'Familjen H.' (The H. Family). Its success was immediate and unmistakable. It not only was received with applause, but created a sensation, and Swedish literature was congratulated on the acquisition of a new talent among its writers.

The secret of Fredrika's authorship--which had as yet not been confided even to her parents--was presently revealed to the poet (and later bishop) Franzén, an old friend of the family. Shortly afterward the Swedish Academy, of which Franzén was secretary, awarded her its lesser gold medal as a sign of appreciation. A third volume met with even greater success than its predecessors, and seemed definitely to point out the career which she subsequently followed; and from this time until the close of her life she worked diligently in her chosen field. She rapidly acquired an appreciative public in and out of Sweden. Many of her novels and tales were translated into various languages, several of them appearing simultaneously in Swedish and English. In 1844 the Swedish Academy awarded her its great gold medal of merit.

Several long journeys abroad mark the succeeding years: to Denmark and America from 1848 to 1857; to Switzerland, Belgium, France, Italy, Palestine, and Greece, from 1856 to 1861; to Germany in 1862, returning the same year. The summer months of 1864 she spent at Årsta, which since 1853 had passed out of the hands of the family. She removed there the year after, and died there on the 31st of December.

Fredrika Bremer's most successful literary work was in the line of her earliest writings, descriptive of the every-day life of the middle classes. Her novels in this line have an unusual charm of expression, whose definable elements are an unaffected simplicity and a certain quiet humor which admirably fits the chosen milieu. Besides the ones already mentioned, 'Presidentens Döttrar' (The President's Daughters), 'Grannarna' (The Neighbors), 'Hemmet' (The Home), 'Nina,' and others, cultivated this field. Later she drifted into "tendency" fiction, making her novels the vehicles for her opinions on important public questions, such as religion, philanthropy, and above all the equal rights of women. These later productions, of which 'Hertha' and 'Syskonlif' are the most important, are far inferior to her earlier work. She had, however, the satisfaction of seeing the realization of several of the movements which she had so ardently espoused: the law that unmarried women in Sweden should attain their majority at twenty-five years of age; the organization at Stockholm of a seminary for the education of woman teachers; and certain parliamentary reforms.

In addition to her novels and short stories, she wrote some verse, mostly unimportant, and several books of travel, among them 'Hemmen i ny Verlden' (Homes in the New World), containing her experiences of America; 'Life in the Old World'; and 'Greece and the Greeks.'

A HOME-COMING

From 'The Neighbors'

LETTER I.--FRANCISCA W. TO MARIA M.

ROSENVIK, 1st June, 18.

Here I am now, dear Maria, in my own house and home, at my own writing-table, and with my own Bear. And who then is Bear? no doubt you ask. Who else should he be but my own husband? I call him Bear because--it so happens. I am seated at the window. The sun is setting. Two swans are swimming in the lake, and furrow its clear mirror. Three cows--my cows--are standing on the verdant margin, quiet, fat, and pensive, and certainly think of nothing. What excellent cows they are! Now the maid is coming up with the milk-pail. Delicious milk in the country! But what is not good in the country? Air and people, food and feelings, earth and sky, everything there is fresh and cheering.

Now I must introduce you to my place of abode--no! I must begin farther off. Upon yonder hill, from which I first beheld the valley in which Rosenvik lies (the hill is some miles in the interior of Smaaland) do you descry a carriage covered with dust? In it are seated Bear and his wedded wife. The wife is looking out with curiosity, for before her lies a valley so beautiful in the tranquillity of evening! Below are green groves which fringe mirror-clear lakes, fields of standing corn bend in silken undulations round gray mountains, and white buildings glance amid the trees. Round about, pillars of smoke are shooting up vertically from the wood-covered hills to the serene evening sky. This seems to indicate the presence of volcanoes, but in point of fact it is merely the peaceful labor of the husbandmen burning the vegetation, in order to fertilize the soil. At all events, it is an excellent thing, and I am delighted, bend forward, and am just thinking about a happy family in nature,--Paradise, and Adam and Eve,--when suddenly Bear puts his great paws around me, and presses me so that I am near giving up the ghost, while, kissing me, he entreats me to "be comfortable here." I was a little provoked; but when I perceived the heartfelt intention of the embrace, I could not but be satisfied.

In this valley, then, was my permanent home: here my new family was living; here lay Rosenvik; here I was to live with my Bear. We descended the hill, and the carriage rolled rapidly along the level way. Bear told me the names of every estate, both in the neighborhood and at a distance. I listened as if I were dreaming, but was roused from my reverie when he said with a certain stress, "Here is the residence of ma chère mère," and the carriage drove into a courtyard, and stopped before a large and fine stone house.

"What, are we going to alight here?" "Yes, my love." This was by no means an agreeable surprise to me. I would gladly have first driven to my own home, there to prepare myself a little for meeting my husband's stepmother, of whom I was a little afraid, from the accounts I had heard of that lady, and the respect Bear entertained for her. This visit appeared entirely mal àpropos to me, but Bear has his own ideas, and I perceived from his manner that it was not expedient then to offer any resistance.

It was Sunday, and on the carriage drawing up, the tones of a violin became audible to me. "Aha!" said Bear, "so much the better;" made a ponderous leap from the carriage, and lifted me out. Of hat-cases and packages, no manner of account was to be taken. Bear took my hand, ushered me up the steps into the magnificent hall, and dragged me toward the door from whence the sounds of music and dancing were heard. "See," thought I, "now I am to dance in this costume forsooth!" I wished to go into some place where I could shake the dust from my nose and my bonnet; where I could at least view myself in a mirror. Impossible! Bear, leading me by the arm, assured me that I looked "most charming," and entreated me to mirror myself in his eyes. I then needs must be so discourteous as to reply that they were "too small." He protested that they were only the clearer, and opened the door to the ball-room. "Well, since you lead me to the ball, you shall also dance with me, you Bear!" I exclaimed in the gayety of despair, so to speak. "With delight!" cried Bear, and at the same moment we found ourselves in the salon.

My alarm diminished considerably when I perceived in the spacious room only a crowd of cleanly attired maids and serving-men, who were sweeping merrily about with one another. They were so busied with dancing as scarcely to observe us. Bear then conducted me to the upper end of the apartment; and there, on a high seat, I saw a tall and strong lady of about fifty, who was playing on a violin with zealous earnestness, and beating time with her foot, which she stamped with energy. On her head she wore a remarkable and high-projecting cap of black velvet, which I will call a helmet, because that word occurred to my mind at the very first view I had of her, and I know no one more appropriate. She looked well, but singular. It was the lady of General Mansfelt, my husband's stepmother, ma chère mère!

She speedily cast her large dark-brown eyes on me, instantly ceased playing, laid aside the violin, and drew herself up with a proud bearing, but an air of gladness and frankness. Bear led me towards her. I trembled a little, bowed profoundly, and kissed ma chère mère's hand. She kissed my forehead, and for a while regarded me with such a keen glance, that I was compelled to abase my eyes, on which she again kissed me most cordially on lips and forehead, and embraced me almost as lustily as Bear had. Now it was Bear's turn; he kissed the hand of ma chère mère right respectfully; she however offered him her cheek, and they appeared very friendly. "Be welcome, my dear friends!" said ma chère mère, with a loud, masculine voice. "It was handsome in you to come to me before driving to your own home. I thank you for it. I would indeed have given you a better reception had I been prepared; at all events, I know that 'Welcome is the best cheer.' I hope, my friends, you stay the evening here?" Bear excused us, said that we desired to get home soon, that I was fatigued from the journey, but that we would not drive by Carlsfors without paying our respects to ma chère mère.

"Well, very good, well, very good!" said ma chère mère, with satisfaction; "we will shortly talk further about that in the chamber there; but first I must say a few words to the people here. Hark ye, good friends!" and ma chère mère knocked with the bow on the back of the violin, till a general silence ensued in the salon. "My children," she pursued in a solemn manner, "I have to tell you--a plague upon you! will you not be still there, at the lower end?--I have to inform you that my dear son, Lars Anders Werner, has now led home, as his wedded wife, this Francisca Burén whom you see at his side. Marriages are made in heaven, my children, and we will supplicate heaven to complete its work in blessing this conjugal pair. We will this evening together drink a bumper to their prosperity. That will do! Now you can continue your dancing, my children. Olof, come you here, and do your best in playing."

While a murmur of exultation and congratulations went through the assembly, ma chère mère took me by the hand, and led me, together with Bear, into another room. Here she ordered punch and glasses to be brought in. In the interim she thrust her two elbows on the table, placed her clenched hands under her chin, and gazed steadfastly at me, but with a look which was rather gloomy than friendly. Bear, perceiving that ma chère mère's review embarrassed me, broached the subject of the harvest or rural affairs. Ma chère mère vented a few sighs, so deep that they rather resembled groans, appeared to make a violent effort to command herself, answered Bear's questions, and on the arrival of the punch, drank to us, saying, with a serious look and voice, "Son and son's wife, your health!" On this she grew more friendly, and said in a tone of pleasantry, which beseemed her very well, "Lars Anders, I don't think people can say you have bought the calf in the sack. Your wife does not by any means look in bad case, and has a pair of eyes to buy fish with. Little she is, it is true; but 'Little and bold is often more than a match for the great.'"

I laughed, so did ma chère mère also; I began to understand her character and manner. We gossiped a little while together in a lively manner, and I recounted some little adventures of travel, which amused her exceedingly. After the lapse of an hour, we arose to take leave, and ma chère mère said, with a really charming smile, "I will not detain you this evening, delighted as I am to see you. I can well imagine that home is attractive. Stay at home to-morrow, if you will; but the day after to-morrow come and dine with me. As to the rest, you know well that you are at all times welcome. Fill now your glasses, and come and drink the folks' health. Sorrow we should keep to ourselves, but share joy in common."

We went into the dancing-room with full glasses, ma chère mère leading the way as herald. They were awaiting us with bumpers, and ma chère mère addressed the people something in this strain:--"We must not indeed laugh until we get over the brook; but when we set out on the voyage of matrimony with piety and good sense, then may be applied the adage that 'Well begun is half won'; and on that, my friends, we will drink a skoal to this wedded pair you see before you, and wish that both they and their posterity may ever 'sit in the vineyard of our Lord.' Skoal!"

"Skoal! skoal!" resounded from every side. Bear and I emptied our glasses, and went about and shook a multitude of people by the hand, till my head was all confusion. When this was over, and we were preparing to prosecute our journey, ma chère mère came after us on the steps with a packet or bundle in her hand, and said in a friendly manner, "Take this cold roast veal with you, children, for breakfast to-morrow morning. After that, you must fatten and consume your own calves. But forget not, daughter-in-law, that I get back my napkin. No, you shan't carry it, dear child, you have enough to do with your bag and mantle. Lars Anders shall carry the roast veal." And as if Lars Anders had been still a little boy, she charged him with the bundle, showed him how he was to carry it, and Bear did as she said. Her last words were, "Forget not that I get my napkin again!" I looked with some degree of wonder at Bear; but he smiled, and lifted me into the carriage.

THE LANDED PROPRIETOR

From 'The Home'

Louise possessed the quality of being a good listener in a higher degree than any one else in the family, and therefore she heard more than any one else of his Excellency; but not of him only, for Jacobi had always something to tell her, always something to consult her about; and in case she were not too much occupied with her thoughts about the weaving, he could always depend upon the most intense sympathy, and the best advice both with regard to moral questions and economical arrangements, dress, plans for the future, and so forth. He also gave her good advice--which however was very seldom followed--when she was playing Postilion; he also drew patterns for her tapestry work, and was very fond of reading aloud to her--but novels rather than sermons.

But he was not long allowed to sit by her side alone; for very soon a person seated himself at her other side whom we will call the Landed Proprietor, as he was chiefly remarkable for the possession of a large estate in the vicinity of the town.

The Landed Proprietor seemed to be disposed to dispute with the Candidate--let us continue to call him so, as we are all, in one way or the other, Candidates in this world--the place which he possessed. The Landed Proprietor had, besides his estate, a very portly body; round, healthy-looking cheeks; a pair of large gray eyes, remarkable for their want of expression; and a little rosy mouth, which preferred mastication to speaking, which laughed without meaning, and which now began to direct to "Cousin Louise"--for he considered himself related to the Lagman--several short speeches, which we will recapitulate in the following chapter, headed

STRANGE QUESTIONS

"Cousin Louise, are you fond of fish--bream for instance?" asked the Landed Proprietor one evening, as he seated himself by the side of Louise, who was busy working a landscape in tapestry.

"Oh, yes! bream is a very good fish," answered she, phlegmatically, without looking up.

"Oh, with red-wine sauce, delicious! I have splendid fishing on my estate, Oestanvik. Big fellows of bream! I fish for them myself."

"Who is the large fish there?" inquired Jacobi of Henrik, with an impatient sneer; "and what is it to him if your sister Louise is fond of bream or not?"

"Because then she might like him too, mon cher! A very fine and solid fellow is my cousin Thure of Oestanvik. I advise you to cultivate his acquaintance. What now, Gabrielle dear, what now, your Highness?"

"What is that which--"

"Yes, what is it? I shall lose my head over that riddle. Mamma dear, come and help your stupid son!"

"No, no! Mamma knows it already. She must not say it!" exclaimed Gabrielle with fear.

"What king do you place above all other kings, Magister?" asked Petrea for the second time,--having this evening her "raptus" of questioning.

"Charles the Thirteenth," answered the Candidate, and listened for what Louise was going to reply to the Landed Proprietor.

"Do you like birds, Cousin Louise?" asked the Landed Proprietor.

"Oh yes, particularly the throstle," answered Louise.

"Well,--I am glad of that!" said the Landed Proprietor. "On my estate, Oestanvik, there is an immense quantity of throstles. I often go out with my gun, and shoot them for my dinner. Piff, paff! with two shots I have directly a whole dishful."

Petrea, who was asked by no one "Do you like birds, cousin?" and who wished to occupy the Candidate, did not let herself be deterred by his evident confusion, but for the second time put the following question:--"Do you think, Magister, that people before the Flood were really worse than they are nowadays?"

"Oh, much, much better," answered the Candidate.

"Are you fond of roasted hare, Cousin Louise?" asked the Landed Proprietor.

"Are you fond of roasted hare, Magister?" whispered Petrea waggishly to Jacobi.

"Brava, Petrea!" whispered her brother to her.

"Are you fond of cold meat, Cousin Louise?" asked the Landed Proprietor, as he was handing Louise to the supper-table.

"Are you fond of Landed Proprietor?" whispered Henrik to her as she left it.

Louise answered just as a cathedral would have answered: she looked very solemn and was silent.

After supper Petrea was quite excited, and left nobody alone who by any possibility could answer her. "Is reason sufficient for mankind? What is the ground of morals? What is properly the meaning of 'revelation'? Why is everything so badly arranged in the State? Why must there be rich and poor?" etc., etc.

"Dear Petrea!" said Louise, "what use can there be in asking those questions?"

It was an evening for questions; they did not end even when the company had broken up.

"Don't you think, Elise," said the Lagman to his wife when they were alone, "that our little Petrea begins to be disagreeable with her continual questioning and disputing? She leaves no one in peace, and is stirred up herself the whole time. She will make herself ridiculous if she keeps on in this way."

"Yes, if she does keep on so. But I have a feeling that she will change. I have observed her very particularly for some time, and do you know, I think there is really something very uncommon in that girl."

"Yes, yes, there is certainly something uncommon in her. Her liveliness and the many games and schemes which she invents--"

"Yes, don't you think they indicate a decided talent for the fine arts? And then her extraordinary thirst for learning: every morning, between three and four o'clock, she gets up in order to read or write, or to work at her compositions. That is not at all a common thing. And may not her uneasiness, her eagerness to question and dispute, arise from a sort of intellectual hunger? Ah, from such hunger, which many women must suffer throughout their lives, from want of literary food,--from such an emptiness of the soul arise disquiet, discontent, nay, innumerable faults."

"I believe you are right, Elise," said the Lagman, "and no condition in life is sadder, particularly in more advanced years. But this shall not be the lot of our Petrea--that I will promise. What do you think now would benefit her most?"

"My opinion is that a serious and continued plan of study would assist in regulating her mind. She is too much left to herself with her confused tendencies, with her zeal and her inquiry. I am too ignorant myself to lead and instruct her, you have too little time, and she has no one here who can properly direct her young and unregulated mind. Sometimes I almost pity her, for her sisters don't understand at all what is going on within her, and I confess it is often painful to myself; I wish I were more able to assist her. Petrea needs some ground on which to take her stand. Her thoughts require more firmness; from the want of this comes her uneasiness. She is like a flower without roots, which is moved about by wind and waves."

"She shall take root, she shall find ground as sure as it is to be found in the world," said the Lagman, with a serious and beaming eye, at the same time striking his hand on the book containing the law of West Gotha, so that it fell to the ground. "We will consider more of this, Elise," continued he: "Petrea is still too young for us to judge with certainty of her talents and tendencies. But if they turn out to be what they appear, then she shall never feel any hunger as long as I live and can procure bread for my family. You know my friend, the excellent Bishop B----: perhaps we can at first confide our Petrea to his guidance. After a few years we shall see; she is still only a child. Don't you think that we ought to speak to Jacobi, in order to get him to read and converse with her? Apropos, how is it with Jacobi? I imagine that he begins to be too attentive to Louise."

"Well, well! you are not so far wrong; and even our cousin Thure of Oestanvik,--have you perceived anything there?"

"Yes, I did perceive something yesterday evening; what the deuce was his meaning with those stupid questions he put to her? 'Does cousin like this?' or 'Is cousin fond of that?' I don't like that at all myself. Louise is not yet full-grown, and already people come and ask her, 'Does cousin like--?' Well, it may signify very little after all, which would perhaps please me best. What a pity, however, that our cousin is not a little more manly; for he has certainly got a most beautiful estate, and so near us."

"Yes, a pity; because, as he is at present, I am almost sure Louise would find it impossible to give him her hand."

"You do not believe that her inclination is toward Jacobi?"

"To tell the truth, I fancy that this is the case."

"Nay, that would be very unpleasant and very unwise: I am very fond of Jacobi, but he has nothing and is nothing."

"But, my dear, he may get something and become something; I confess, dear Ernst, that I believe he would suit Louise better for a husband than any one else we know, and I would with pleasure call him my son."

"Would you, Elise? then I must also prepare myself to do the same. You have had most trouble and most labor with the children, it is therefore right that you should decide in their affairs."

"Ernst, you are so kind!"

"Say just, Elise; not more than just. Besides, it is my opinion that our thoughts and inclinations will not differ much. I confess that Louise appears to me to be a great treasure, and I know of nobody I could give her to with all my heart; but if Jacobi obtains her affections, I feel that I could not oppose their union, although it would be painful to me on account of his uncertain prospects. He is really dear to me, and we are under great obligations to him on account of Henrik; his excellent heart, his honesty, and his good qualities, will make him as good a citizen as a husband and father, and I consider him to be one of the most agreeable men to associate with daily. But, God bless me! I speak as if I wished the union, but that is far from my desire: I would much rather keep my daughters at home, so long as they find themselves happy with me; but when girls grow up, there is never any peace to depend on. I wish all lovers and questioners a long way off. Here we could live altogether as in a kingdom of heaven, now that we have got everything in such order. Some small improvements may still be wanted, but this will be all right if we are only left in peace. I have been thinking that we could so easily make a wardrobe here: do you see on this side of the wall--don't you think if we were to open--What! are you asleep already, my dear?"

Louise was often teased about Cousin Thure; Cousin Thure was often teased about Cousin Louise. He liked very much to be teased about his Cousin Louise, and it gave him great pleasure to be told that Oestanvik wanted a mistress, that he himself wanted a good wife, and that Louise Frank was decidedly one of the wisest and most amiable girls in the whole neighborhood, and of the most respectable family. The Landed Proprietor was half ready to receive congratulations on his betrothal. What the supposed bride thought about the matter, however, is difficult to divine. Louise was certainly always polite to her "Cousin Thure," but more indifference than attachment seemed to be expressed in this politeness; and she declined, with a decision astonishing to many a person, his constantly repeated invitations to make a tour to Oestanvik in his new landau drawn by "my chestnut horses," four-in-hand. It was said by many that the agreeable and friendly Jacobi was much nearer to Louise's heart than the rich Landed Proprietor. But even towards Jacobi her behavior was so uniform, so quiet, and so unconstrained that nobody knew what to think. Very few knew so well as we do that Louise considered it in accordance with the dignity of a woman to show perfect indifference to the attentions or doux propos of men, until they had openly and fully explained themselves. She despised coquetry to that degree that she feared everything which had the least appearance of it. Her young friends used to joke with her upon her strong notions in this respect, and often told her that she would remain unmarried.

"That may be!" answered Louise calmly.

One day she was told that a gentleman had said, "I will not stand up for any girl who is not a little coquettish!"

"Then he may remain sitting!" answered Louise, with a great deal of dignity.

Louise's views with regard to the dignity of woman, her serious and decided principles, and her manner of expressing them, amused her young friends, at the same time that they inspired them with great regard for her, and caused many little contentions and discussions in which Louise fearlessly, though not without some excess, defended what was right. These contentions, which began in merriment, sometimes ended quite differently.

A young and somewhat coquettish married lady felt herself one day wounded by the severity with which Louise judged the coquetry of her sex, particularly of married ladies, and in revenge she made use of some words which awakened Louise's astonishment and anger at the same time. An explanation followed between the two, the consequence of which was a complete rupture between Louise and the young lady, together with an altered disposition of mind in the former, which she in vain attempted to conceal. She had been unusually joyous and lively during the first days of her stay at Axelholm; but she now became silent and thoughtful, often absent; and some people thought that she seemed less friendly than formerly towards the Candidate, but somewhat more attentive to the Landed Proprietor, although she constantly declined his invitation "to take a tour to Oestanvik."

The evening after this explanation took place, Elise was engaged with Jacobi in a lively conversation in the balcony.

"And if," said Jacobi, "if I endeavor to win her affections, oh, tell me! would her parents, would her mother see it without displeasure? Ah, speak openly with me; the happiness of my life depends upon it!"

"You have my approval and my good wishes," answered Elise; "I tell you now what I have often told my husband, that I should very much like to call you my son!"

"Oh!" exclaimed Jacobi, deeply affected, falling on his knees and pressing Elise's hand to his lips: "oh, that every act in my life might prove my gratitude, my love--!"

At this moment Louise, who had been looking for her mother, approached the balcony; she saw Jacobi's action and heard his words. She withdrew quickly, as if she had been stung by a serpent.

From this time a great change was more and more perceptible in her. Silent, shy, and very pale, she moved about like a dreaming person in the merry circle at Axelholm, and willingly agreed to her mother's proposal to shorten her stay at this place.

Jacobi, who was as much astonished as sorry at Louise's sudden unfriendliness towards him, began to think the place was somehow bewitched, and wished more than once to leave it.

A FAMILY PICTURE

From 'The Home'

The family is assembled in the library; tea is just finished. Louise, at the pressing request of Gabrielle and Petrea, lays out the cards in order to tell the sisters their fortune. The Candidate seats himself beside her, and seems to have made up his mind to be a little more cheerful. But then "the object" looks more like a cathedral than ever. The Landed Proprietor enters, bows, blows his nose, and kisses the hand of his "gracious aunt."

Landed Proprietor--Very cold this evening; I think we shall have frost.

Elise--It is a miserable spring; we have just read a melancholy account of the famine in the northern provinces; these years of dearth are truly unfortunate.

Landed Proprietor--Oh yes, the famine up there. No, let us talk of something else; that is too gloomy. I have had my peas covered with straw. Cousin Louise, are you fond of playing Patience? I am very fond of it myself; it is so composing. At Oestanvik I have got very small cards for Patience; I am quite sure you would like them, Cousin Louise.

The Landed Proprietor seats himself on the other side of Louise. The Candidate is seized with a fit of curious shrugs.

Louise--This is not Patience, but a little conjuring by means of which I can tell future things. Shall I tell your fortune, Cousin Thure?

Landed Proprietor--Oh yes! do tell my fortune; but don't tell me anything disagreeable. If I hear anything disagreeable in the evening, I always dream of it at night. Tell me now from the cards that I shall have a pretty little wife;--a wife beautiful and amiable as Cousin Louise.

The Candidate (with an expression in his eyes as if he would send the Landed Proprietor head-over-heels to Oestanvik)--I don't know whether Miss Louise likes flattery.

Landed Proprietor (who takes no notice of his rival)--Cousin Louise, are you fond of blue?

Louise--Blue? It is a pretty color; but I almost like green better.

Landed Proprietor--Well, that's very droll; it suits exceedingly well. At Oestanvik my drawing-room furniture is blue; beautiful light-blue satin. But in my bedroom I have green moreen. Cousin Louise, I believe really--

The Candidate coughs as though he were going to be suffocated, and rushes out of the room. Louise looks after him and sighs, and afterwards sees in the cards so many misfortunes for Cousin Thure that he is quite frightened. "The peas frosted!"--"conflagration in the drawing-room"--and at last "a basket" ["the mitten"]. The Landed Proprietor declares still laughingly that he will not receive "a basket." The sisters smile and make their remarks.

CLEMENS BRENTANO

(1778-1842)

he intellectual upheaval in Germany at the beginning of this century brought a host of remarkable characters upon the literary stage, and none more gifted, more whimsical, more winning than Clemens Brentano, the erratic son of a brilliant family. Born September 8th, 1778, at Ehrenbreitstein, Brentano spent his youth among the stimulating influences which accompanied the renaissance of German culture. His grandmother, Sophie de la Roche, had been the close friend of Wieland, and his mother the youthful companion of Goethe. Clemens, after a vain attempt to follow in the mercantile footsteps of his father, went to Jena, where he met the Schlegels; and here his brilliant but unsteady literary career began.

In 1803 he married the talented Sophie Mareau, but three years later his happiness was terminated by her death. His next matrimonial venture was, however, a failure: an elopement in 1808 with the daughter of a Frankfort banker was quickly followed by a divorce, and he thereafter led the uncontrolled life of an errant poet. Among his early writings, published under the pseudonym of 'Marie,' were several satires and dramas and a novel entitled 'Godwi,' which he himself called "a romance gone mad." The meeting with Achim von Arnim, who subsequently married his sister Bettina, decided his fate: he embarked in literature once and for all in close association with Von Arnim. Together they compiled a collection of several hundred folk-songs of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, under the name of 'Des Knaben Wunderhorn' (The Boy's Wonderhorn), 1806-1808. That so musical a people as the Germans should be masters of lyric poetry is but natural,--every longing, every impression, every impulse gushes into song; and in 'Des Knaben Wunderhorn' we hear the tuneful voices of a naïve race, singing what they have seen or dreamed or felt during three hundred years. The work is dedicated to Goethe, who wrote an almost enthusiastic review of it for the Literary Gazette of Jena. "Every lover or master of musical art," he says, "should have this volume upon his piano."

The 'Wunderhorn' was greeted by the German public with extraordinary cordiality. It was in fact an epoch-making work, the pioneer in the new field of German folk poetry. It carried out in a purely national spirit the efforts which Herder had made in behalf of the folk-songs of all peoples. It revealed the spirit of the time. 1806 was the year of the battle of Jena, and Germany in her hour of deepest humiliation gave ear to the encouraging voices from out her own past. "The editors of the 'Wunderhorn,'" said their friend Görres, "have deserved of their countrymen a civic crown, for having saved from destruction what yet remained to be saved;" and on this civic crown the poets' laurels are still green.

Brentano's contagious laughter may even now be heard re-echoing through the pages of his book on 'The Philistine' (1811). His dramatic power is evinced in the broadly conceived play 'Die Gründung Prags' (The Founding of Prague: 1815); but it is upon two stories, told in the simple style of the folk-tale, that his widest popularity is founded. 'Die Geschichte vom braven Casperl und der schönen Annerl' (The Story of Good Casper and Pretty Annie) and his fable of 'Gockel, Hinkel, und Gackeleia,' both of the year 1838, are still an indispensable part of the reading of every German boy and girl.

Like his brilliant sister, Brentano is a fascinating figure in literature. He was amiable and winning, full of quips and cranks, and with an inexhaustible fund of stories. Astonishing tales of adventure, related with great circumstantiality of detail, and of which he himself was the hero, played an important part in his conversation. Tieck once said he had never known a better improvisatore than Brentano, nor one who could "lie more gracefully."

When Brentano was forty years of age a total change came over his life. The witty and fascinating man of the world was transformed into a pious and gloomy ascetic. The visions of the stigmatized nun of Dülmen, Katharina Emmerich, attracted him, and he remained under her influence until her death in 1824. These visions he subsequently published as the 'Life of the Virgin Mary.' The eccentricities of his later years bordered upon insanity. He died in the Catholic faith in the year 1842.

THE NURSE'S WATCH

From 'The Boy's Wonderhorn'

The moon it shines,

My darling whines;

The clock strikes twelve:--God cheer

The sick both far and near.

God knoweth all;

Mousy nibbles in the wall;

The clock strikes one:--like day,

Dreams o'er thy pillow play.

The matin-bell

Wakes the nun in convent cell;

The clock strikes two:--they go

To choir in a row.

The wind it blows,

The cock he crows;

The clock strikes three:--the wagoner

In his straw bed begins to stir.

The steed he paws the floor,

Creaks the stable door;

The clock strikes four:--'tis plain

The coachman sifts his grain.

The swallow's laugh the still air shakes,

The sun awakes;

The clock strikes five:--the traveler must be gone,

He puts his stockings on.

The hen is clacking,

The ducks are quacking;

The clock strikes six:--awake, arise,

Thou lazy hag; come, ope thy eyes.

Quick to the baker's run;

The rolls are done;

The clock strikes seven:--

'Tis time the milk were in the oven.

Put in some butter, do,

And some fine sugar, too;

The clock strikes eight:--

Now bring my baby's porridge straight.

Englished by Charles T. Brooks.

THE CASTLE IN AUSTRIA

From 'The Boy's Wonderhorn'

There lies a castle in Austria,

Right goodly to behold,

Walled tip with marble stones so fair,

With silver and with red gold.

Therein lies captive a young boy,

For life and death he lies bound,

Full forty fathoms under the earth,

'Midst vipers and snakes around.

His father came from Rosenberg,

Before the tower he went:--

"My son, my dearest son, how hard

Is thy imprisonment!"

"O father, dearest father mine,

So hardly I am bound,

Full forty fathoms under the earth,

'Midst vipers and snakes around!"

His father went before the lord:--

"Let loose thy captive to me!

I have at home three casks of gold,

And these for the boy I'll gi'e."

"Three casks of gold, they help you not:

That boy, and he must die!

He wears round his neck a golden chain;

Therein doth his ruin lie."

"And if he thus wear a golden chain,

He hath not stolen it; nay!

A maiden good gave it to him

For true love, did she say."

They led the boy forth from the tower,

And the sacrament took he:--

"Help thou, rich Christ, from heaven high,

It's come to an end with me!"

They led him to the scaffold place,

Up the ladder he must go:--

"O headsman, dearest headsman, do

But a short respite allow!"

"A short respite I must not grant;

Thou wouldst escape and fly:

Reach me a silken handkerchief

Around his eyes to tie."

"Oh, do not, do not bind mine eyes!

I must look on the world so fine;

I see it to-day, then never more,

With these weeping eyes of mine."

His father near the scaffold stood,

And his heart, it almost rends:--

"O son, O thou my dearest son,

Thy death I will avenge!"

"O father, dearest father mine!

My death thou shalt not avenge:

'Twould bring to my soul but heavy pains;

Let me die in innocence.

"It is not for this life of mine,

Nor for my body proud;

'Tis but for my dear mother's sake:

At home she weeps aloud."

Not yet three days had passed away,

When an angel from heaven came down:

"Take ye the boy from the scaffold away;

Else the city shall sink under ground!"

And not six months had passed away,

Ere his death was avenged amain;

And upwards of three hundred men

For the boy's life were slain.

Who is it that hath made this lay,

Hath sung it, and so on?

That, in Vienna in Austria,

Three maidens fair have done.

ELISABETH BRENTANO (BETTINA VON ARNIM)

(1785-1859)

o picture of German life at the beginning of this century would be complete which did not include the distinguished women who left their mark upon the time. Among these Bettina von Arnim stands easily foremost. There was something triumphant in her nature, which in her youth manifested itself in her splendid enthusiasm for the two great geniuses who dominated her life,--Goethe and Beethoven,--and which, in the lean years when Germany was overclouded, maintained itself by an inexhaustible optimism. Her merry willfulness and wit covered a warm heart and a vigorous mind; and both of her great idols understood her and took her seriously.

Elisabeth Brentano

Elisabeth Brentano was the daughter of Goethe's friend, Maximiliane de la Roche. She was born at Frankfort-on-the-Main in 1785, and was brought up after the death of her mother under the somewhat peculiar influence of the highly-strung Caroline von Günderode. Through her filial intimacy with Goethe's mother, she came to know the poet; and out of their friendship grew the correspondence which formed the basis of Bettina's famous book, 'Goethe's Briefwechsel mit einem Kinde' (Goethe's Correspondence with a Child). She attached herself with unbounded enthusiasm to Goethe, and he responded with affectionate tact. To him Bettina was the embodiment of the loving grace and willfulness of 'Mignon.'

In 1811 these relations were interrupted, owing to Bettina's attitude toward Goethe's wife. In the same year she married Achim von Arnim, one of the most refined poets and noblest characters of that brilliant circle. The marriage was an ideal one; each cherished and delighted in the genius of the other, but in 1831 the death of Von Arnim brought this happiness to an end. Goethe died in the following year, and Germany went into mourning. Then in 1835 Bettina appeared before the world for the first time as an authoress, in 'Goethe's Correspondence with a Child.' The dithyrambic exaltation, the unrestrained but beautiful enthusiasm of the book came like an electric shock. Into an atmosphere of spiritual stagnation, these letters brought a fresh access of vitality and hope. Bettina's old friendly relations with Goethe had been resumed later in life, and in a letter written to her niece she gives a charming account of the visit to the poet in 1824, which proved to be her last. This letter first saw the light in 1896, and an extract from it has been included below.

The inspiration which went out from Bettina's magnetic nature was profound. She had her part in every great movement of her time, from the liberation of Greece to the fight with cholera in Berlin. During the latter, her devotion to the cause of the suffering poor in Berlin opened her eyes to the miseries of the common people; and she wrote a work full of indignant fervor, 'Dies Buch gehört dem König' (This Book belongs to the King), in consequence of which her welcome at the court of Frederick William IV. grew cool. A subsequent book, written in a similar vein, was suppressed. But Bettina's love of the people, as of every cause in which she was interested, was genuine and not to be quenched; she acted upon the maxim once expressed by Emerson, "Every brave heart must treat society as a child, and never allow it to dictate." Emerson greatly admired Bettina, and Louisa M. Alcott relates that she first made acquaintance with the famous 'Correspondence' when in her girlhood she was left to browse in Emerson's library. Bettina's influence was most keenly felt by the young, and she had the youth of Germany at her feet. She died in 1859.

There is in Weimar a picture in which are represented the literary men of the period, grouped as in Raphael's School of Athens, with Goethe and Schiller occupying the centre. Upon the broad steps which lead to the elevation where they are standing, is the girlish figure of Bettina bending forward and holding a laurel wreath in her hand. This is the position which she occupies in the history of German literature.

DEDICATION: TO GOETHE

From 'Goethe's Correspondence with a Child'

Thou, who knowest love, and the refinement of sentiment, oh how beautiful is everything in thee! How the streams of life rush through thy sensitive heart, and plunge with force into the cold waves of thy time, then boil and bubble up till mountain and vale flush with the glow of life, and the forests stand with glistening boughs upon the shore of thy being, and all upon which rests thy glance is filled with happiness and life! O God, how happy were I with thee! And were I winging my flight far over all times, and far over thee, I would fold my pinions and yield myself wholly to the domination of thine eyes.

Men will never understand thee, and those nearest to thee will most thoroughly disown and betray thee; I look into the future, and I hear them cry, "Stone him!" Now, when thine own inspiration, like a lion, stands beside thee and guards thee, vulgarity ventures not to approach thee. Thy mother said recently, "The men to-day are all like Gerning, who always says, 'We, the superfluous learned';" and she speaks truly, for he is superfluous. Rather be dead than superfluous! But I am not so, for I am thine, because I recognize thee in all things. I know that when the clouds lift themselves up before the sun-god, they will soon be depressed by his fiery hand; I know that he endures no shadow except that which his own fame seeks; the rest of consciousness will overshadow thee. I know, when he descends in the evening, that he will again appear in the morning with golden front. Thou art eternal, therefore it is good for me to be with thee.

When, in the evening, I am alone in my dark room, and the neighbors' lights are thrown upon my wall, they sometimes light up thy bust; or when all is silent in the city, here and there a dog barks or a cock crows: I know not why, but it seems something beyond human to me; I know what I shall do to still my pain.

I would fain speak with thee otherwise than with words; I would fain press myself to thy heart. I feel that my soul is aflame. How fearfully still is the air before the storm! So stand now my thoughts, cold and silent, and my heart surges like the sea. Dear, dear Goethe! A reminiscence of thee breaks the spell; the signs of fire and warfare sink slowly down in my sky, and thou art like the in-streaming moonlight. Thou art great and glorious, and better than all that I have ever known and experienced up to this time. Thy whole life is so good!

TO GOETHE

CASSEL, August 13th, 1807.