автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Library of the World's Best Literature, Ancient and Modern — Volume 3

LIBRARY OF THE

WORLD'S BEST LITERATURE

ANCIENT AND MODERN

CHARLES DUDLEY WARNER

EDITOR

HAMILTON WRIGHT MABIE

LUCIA GILBERT RUNKLE

GEORGE HENRY WARNER

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Connoisseur Edition

VOL. III.

1896

THE ADVISORY COUNCIL

CRAWFORD H. TOY, A.M., LL.D.,

Professor of Hebrew,

HARVARD UNIVERSITY, Cambridge, Mass.

THOMAS R. LOUNSBURY, LL.D., L.H.D.,

Professor of English in the Sheffield Scientific School of

YALE UNIVERSITY, New Haven, Conn.

WILLIAM M. SLOANE, PH.D., L.H.D.,

Professor of History and Political Science,

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY, Princeton, N.J.

BRANDER MATTHEWS, A.M., LL.B.,

Professor of Literature,

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, New York City.

JAMES B. ANGELL, LL.D.,

President of the

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, Ann Arbor, Mich.

WILLARD FISKE, A.M., PH.D.,

Late Professor of the Germanic and Scandinavian Languages and Literatures,

CORNELL UNIVERSITY, Ithaca, N.Y.

EDWARD S. HOLDEN, A.M., LL.D.,

Director of the Lick Observatory, and Astronomer

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, Berkeley, Cal.

ALCÉE FORTIER, LIT.D.,

Professor of the Romance Languages,

TULANE UNIVERSITY, New Orleans, La.

WILLIAM P. TRENT, M.A.,

Dean of the Department of Arts and Sciences, and Professor of English and History,

UNIVERSITY OF THE SOUTH, Sewanee, Tenn.

PAUL SHOREY, PH.D.,

Professor of Greek and Latin Literature,

UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO, Chicago, Ill.

WILLIAM T. HARRIS, LL.D.,

United States Commissioner of Education,

BUREAU OF EDUCATION, Washington, D.C.

MAURICE FRANCIS EGAN, A.M., LL.D.,

Professor of Literature in the

CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA, Washington, D.C.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

VOL. III.

BERTHOLD AUERBACH--Continued: -- 1812-1882

The First False Step ('On the Heights')

The New Home and the Old One (same)

The Court Physician's Philosophy (same)

In Countess Irma's Diary (same)

ÉMILE AUGIER -- 1820-1889

A Conversation with a Purpose ('Giboyer's Boy')

A Severe Young Judge ('The Adventuress')

A Contented Idler ('M. Poirier's Son-in-Law')

Feelings of an Artist (same)

A Contest of Wills ('The Fourchambaults')

ST. AUGUSTINE OF HIPPO (by Samuel Hart) -- 354-430

The Godly Sorrow that Worketh Repentance ('The Confessions')

Consolation (same)

The Foes of the City ('The City of God')

The Praise of God (same)

A Prayer ('The Trinity')

MARCUS AURELIUS ANTONINUS -- A.D. 121-180

Reflections

JANE AUSTEN -- 1775-1817

An Offer of Marriage ('Pride and Prejudice')

Mother and Daughter (same)

A Letter of Condolence (same)

A Well-Matched Sister and Brother ('Northanger Abbey')

Family Doctors ('Emma')

Family Training ('Mansfield Park')

Private Theatricals (same)

Fruitless Regrets and Apples of Sodom (same)

AVERROËS -- 1126-1198

THE AVESTA (by A.V. Williams Jackson)

Psalm of Zoroaster

Prayer for Knowledge

The Angel of Divine Obedience

To the Fire

The Goddess of the Waters

Guardian Spirits

An Ancient Sindbad

The Wise Man

Invocation to Rain

Prayer for Healing

Fragment

AVICEBRON -- 1028-?1058

On Matter and Form ('The Fountain of Life')

ROBERT AYTOUN -- 1570-1638

Inconstancy Upbraided

Lines to an Inconstant Mistress (with Burns's Adaptation)

WILLIAM EDMONSTOUNE AYTOUN -- 1813-1865

Burial March of Dundee ('Lays of the Scottish Cavaliers')

Execution of Montrose (same)

The Broken Pitcher ('Bon Gaultier Ballads')

Sonnet to Britain. "By the Duke of Wellington" (same)

A Ball in the Upper Circles ('The Modern Endymion')

A Highland Tramp ('Norman Sinclair')

MASSIMO TAPARELLI D'AZEGLIO -- 1798-1866

A Happy Childhood ('My Recollections')

The Priesthood (same)

My First Venture in Romance (same)

BABER (by Edward S. Holden) -- 1482-1530

From Baber's 'Memoirs'

BABRIUS -- First Century A.D.

The North Wind and the Sun

Jupiter and the Monkey

The Mouse that Fell into the Pot

The Fox and the Grapes

The Carter and Hercules

The Young Cocks

The Arab and the Camel

The Nightingale and the Swallow

The Husbandman and the stork

The Pine

The Woman and Her Maid-Servants

The Lamp

The Tortoise and the Hare

FRANCIS BACON (by Charlton T. Lewis) -- 1561-1626

Of Truth ('Essays')

Of Revenge (same)

Of Simulation and Dissimulation (same)

Of Travel (same)

Of Friendship (same)

Defects of the Universities ('The Advancement of Learning')

To My Lord Treasurer Burghley

In Praise of Knowledge

To the Lord Chancellor

To Villiers on his Patent as a Viscount

Charge to Justice Hutton

A Prayer, or Psalm

From the 'Apophthegms'

Translation of the 137th Psalm

The World's a Bubble

WALTER BAGEHOT (by Forrest Morgan) -- 1826-1877

The Virtues of Stupidity ('Letters on the French Coup d'État')

Review Writing ('The First Edinburgh Reviewers')

Lord Eldon (same)

Taste ('Wordsworth, Tennyson, and Browning')

Causes of the Sterility of Literature ('Shakespeare')

The Search for Happiness ('William Cowper')

On Early Reading ('Edward Gibbon')

The Cavaliers ('Thomas Babington Macaulay')

Morality and Fear ('Bishop Butler')

The Tyranny of Convention ('Sir Robert Peel')

How to Be an Influential Politician ('Bolingbroke')

Conditions of Cabinet Government ('The English Constitution')

Why Early Societies could not be Free ('Physics and Politics')

Benefits of Free Discussion in Modern Times (same)

Origin of Deposit Banking ('Lombard Street')

JENS BAGGESEN -- 1764-1826

A Cosmopolitan ('The Labyrinth')

Philosophy on the Heath (same)

There was a Time when I was Very Little

PHILIP JAMES BAILEY -- 1816-

From "Festus": Life: The Passing-Bell; Thoughts;

Dreams; Chorus of the Saved

JOANNA BAILLIE -- 1762-1851

Woo'd and Married and A'

It Was on a Morn when We were Thrang

Fy, Let Us A' to the Wedding

The Weary Pund o' Tow

From 'De Montfort'

To Mrs. Siddons

A Scotch Song

Song, 'Poverty Parts Good Company'

The Kitten

HENRY MARTYN BAIRD -- 1832-

The Battle of Ivry ('The Huguenots and Henry of Navarre')

SIR SAMUEL WHITE BAKER -- 1821-1893

Hunting in Abyssinia ('The Nile Tributaries of Abyssinia')

The Sources of the Nile ('The Albert Nyanza')

ARTHUR JAMES BALFOUR -- 1848-

The Pleasures of Reading (Rectorial Address)

THE BALLAD (by F.B. Gummere)

Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne

The Hunting of the Cheviot

Johnie Cock

Sir Patrick Spens

The Bonny Earl of Murray

Mary Hamilton

Bonnie George Campbell

Bessie Bell and Mary Gray

The Three Ravens

Lord Randal

Edward

The Twa Brothers

Babylon

Childe Maurice

The Wife of Usher's Well

Sweet William's Ghost

HONORÉ DE BALZAC (by William P. Trent) -- 1799-1850

The Meeting in the Convent ('The Duchess of Langeais')

An Episode Under the Terror

A Passion in the Desert

The Napoleon of the People ('The Country Doctor')

GEORGE BANCROFT (by Austin Scott) -- 1800-1891

The Beginnings of Virginia ('History of the United States')

Men and Government in Early Massachusetts (same)

King Philip's War (same)

The New Netherland (same)

Franklin (same)

FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

VOLUME III.

Ancient Irish Miniature (Colored Plate)

Frontispiece

"St. Augustine and His Mother" (Photogravure)

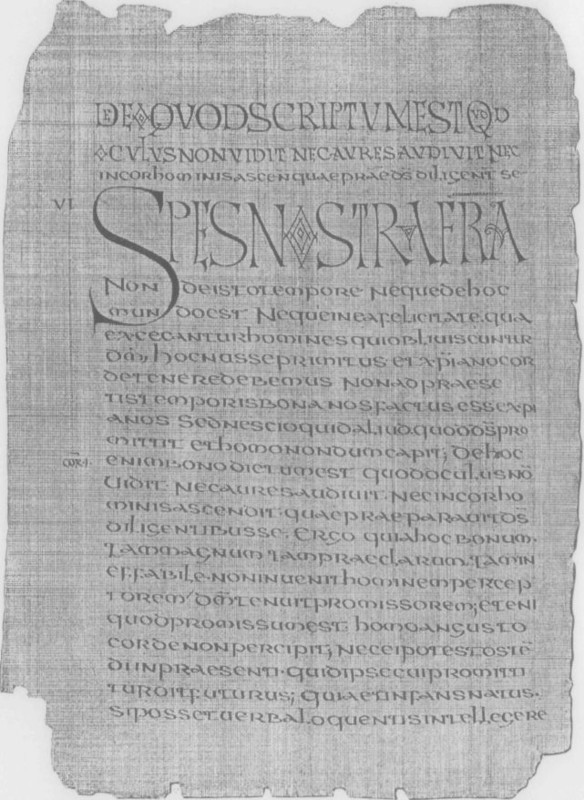

1014Papyrus, Sermons of St. Augustine (Fac-simile)

1018Marcus Aurelius (Portrait)

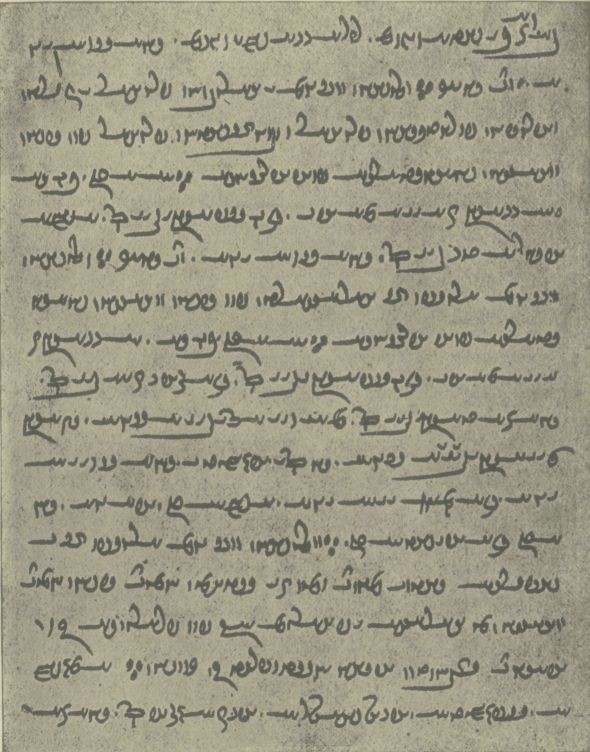

1022The Zend Avesta (Fac-simile)

1084Francis Bacon (Portrait)

1156"The Cavaliers" (Photogravure)

1218Honoré de Balzac (Portrait)

1348George Bancroft (Portrait)

1432

VIGNETTE PORTRAITS

Émile Augier

Jane Austen

Robert Aytoun

Walter Bagehot

Jens Baggesen

Philip James Bailey

Joanna Baillie

Henry Martyn Baird

Sir Samuel White Baker

Arthur James Balfour

BERTHOLD AUERBACH--(Continued from Volume II)

"Do you imagine that every one is kindly disposed towards you? Take my word for it, a palace contains people of all sorts, good and bad. All the vices abound in such a place. And there are many other matters of which you have no idea, and of which you will, I trust, ever remain ignorant. But all you meet are wondrous polite. Try to remain just as you now are, and when you leave the palace, let it be as the same Walpurga you were when you came here."

Walpurga stared at her in surprise. Who could change her?

Word came that the Queen was awake and desired Walpurga to bring the Crown Prince to her.

Accompanied by Doctor Gunther, Mademoiselle Kramer, and two waiting-women, she proceeded to the Queen's bedchamber. The Queen lay there, calm and beautiful, and with a smile of greeting, turned her face towards those who had entered. The curtains had been partially drawn aside, and a broad, slanting ray of light shone into the apartment, which seemed still more peaceful than during the breathless silence of the previous night.

"Good morning!" said the Queen, with a voice full of feeling. "Let me have my child!" She looked down at the babe that rested in her arms, and then, without noticing any one in the room, lifted her glance on high and faintly murmured:--

"This is the first time I behold my child in the daylight!"

All were silent; it seemed as if there was naught in the apartment except the broad slanting ray of light that streamed in at the window.

"Have you slept well?" inquired the Queen. Walpurga was glad the Queen had asked a question, for now she could answer. Casting a hurried glance at Mademoiselle Kramer, she said:--

"Yes, indeed! Sleep's the first, the last, and the best thing in the world."

"She's clever," said the Queen, addressing Doctor Gunther in French.

Walpurga's heart sank within her. Whenever she heard them speak French, she felt as if they were betraying her; as if they had put on an invisible cap, like that worn by the goblins in the fairy-tale, and could thus speak without being heard.

"Did the Prince sleep well?" asked the Queen.

Walpurga passed her hand over her face, as if to brush away a spider that had been creeping there. The Queen doesn't speak of her "child" or her "son," but only of "the Crown Prince."

Walpurga answered:--

"Yes, quite well, thank God! That is, I couldn't hear him, and I only wanted to say that I'd like to act towards the--" she could not say "the Prince"--"that is, towards him, as I'd do with my own child. We began on the very first day. My mother taught me that. Such a child has a will of its own from the very start, and it won't do to give way to it. It won't do to take it from the cradle, or to feed it, whenever it pleases; there ought to be regular times for all those things. It'll soon get used to that, and it won't harm it either, to let it cry once in a while. On the contrary, that expands the chest."

"Does he cry?" asked the Queen.

The infant answered the question for itself, for it at once began to cry most lustily.

"Take him and quiet him," begged the Queen.

The King entered the apartment before the child had stopped crying.

"He will have a good voice of command," said he, kissing the Queen's hand.

Walpurga quieted the child, and she and Mademoiselle Kramer were sent back to their apartments.

The King informed the Queen of the dispatches that had been received, and of the sponsors who had been decided upon. She was perfectly satisfied with the arrangements that had been made.

When Walpurga had returned to her room and had placed the child in the cradle, she walked up and down and seemed quite agitated.

"There are no angels in this world!" said she. "They're all just like the rest of us, and who knows but--" She was vexed at the Queen: "Why won't she listen patiently when her child cries? We must take all our children bring us, whether it be joy or pain."

She stepped out into the passage-way and heard the tones of the organ in the palace-chapel. For the first time in her life these sounds displeased her. "It don't belong in the house," thought she, "where all sorts of things are going on. The church ought to stand by itself."

When she returned to the room, she found a stranger there. Mademoiselle Kramer informed her that this was the tailor to the Queen.

Walpurga laughed outright at the notion of a "tailor to the Queen." The elegantly attired person looked at her in amazement, while Mademoiselle Kramer explained to her that this was the dressmaker to her Majesty the Queen, and that he had come to take her measure for three new dresses.

"Am I to wear city clothes?"

"God forbid! You're to wear the dress of your neighborhood, and can order a stomacher in red, blue, green, or any color that you like best."

"I hardly know what to say; but I'd like to have a workday suit too. Sunday clothes on week-days--that won't do."

"At court one always wears Sunday clothes, and when her Majesty drives out again you will have to accompany her."

"A11 right, then. I won't object."

While he took her measure, Walpurga laughed incessantly, and he was at last obliged to ask her to hold still, so that he might go on with his work. Putting his measure into his pocket, he informed Mademoiselle Kramer that he had ordered an exact model, and that the master of ceremonies had favored him with several drawings, so that there might be no doubt of success.

Finally he asked permission to see the Crown Prince. Mademoiselle Kramer was about to let him do so, but Walpurga objected.

"Before the child is christened," said she, "no one shall look at it just out of curiosity, and least of all a tailor, or else the child will never turn out the right sort of man."

The tailor took his leave, Mademoiselle Kramer having politely hinted to him that nothing could be done with the superstition of the lower orders, and that it would not do to irritate the nurse.

This occurrence induced Walpurga to administer the first serious reprimand to Mademoiselle Kramer. She could not understand why she was so willing to make an exhibition of the child. "Nothing does a child more harm than to let strangers look at it in its sleep, and a tailor at that."

All the wild fun with which, in popular songs, tailors are held up to scorn and ridicule, found vent in Walpurga, and she began singing:--

"Just list, ye braves, who love to roam!

A snail was chasing a tailor home.

And if Old Shears hadn't run so fast,

The snail would surely have caught him at last."

Mademoiselle Kramer's acquaintance with the court tailor had lowered her in Walpurga's esteem; and with an evident effort to mollify the latter, Mademoiselle Kramer asked:--

"Does the idea of your new and beautiful clothes really afford you no pleasure?"

"To be frank with you, no! I don't wear them for my own sake, but for that of others, who dress me to please themselves. It's all the same to me, however! I've given myself up to them, and suppose I must submit."

"May I come in?" asked a pleasant voice. Countess Irma entered the room. Extending both her hands to Walpurga, she said:--

"God greet you, my countrywoman! I am also from the Highlands, seven hours distance from your village. I know it well, and once sailed over the lake with your father. Does he still live?"

"Alas! no: he was drowned, and the lake hasn't given up its dead."

"He was a fine-looking old man, and you are the very image of him."

"I am glad to find some one else here who knew my father. The court tailor--I mean the court doctor--knew him too. Yes, search the land through, you couldn't have found a better man than my father, and no one can help but admit it."

"Yes: I've often heard as much."

"May I ask your Ladyship's name?"

"Countess Wildenort."

"Wildenort? I've heard the name before. Yes, I remember my mother's mentioning it. Your father was known as a very kind and benevolent man. Has he been dead a long while?"

"No, he is still living."

"Is he here too?"

"No."

"And as what are you here, Countess?"

"As maid of honor."

"And what is that?"

"Being attached to the Queen's person; or what, in your part of the country, would be called a companion."

"Indeed! And is your father willing to let them use you that way?"

Irma, who was somewhat annoyed by her questions, said:--

"I wished to ask you something--Can you write?"

"I once could, but I've quite forgotten how."

"Then I've just hit it! that's the very reason for my coming here. Now, whenever you wish to write home, you can dictate your letter to me, and I will write whatever you tell me to."

"I could have done that too," suggested Mademoiselle Kramer, timidly; "and your Ladyship would not have needed to trouble yourself."

"No, the Countess will write for me. Shall it be now?"

"Certainly."

But Walpurga had to go to the child. While she was in the next room, Countess Irma and Mademoiselle Kramer engaged each other in conversation.

When Walpurga returned, she found Irma, pen in hand, and at once began to dictate.

Translation of S.A. Stern.

THE FIRST FALSE STEP

From 'On the Heights'

The ball was to be given in the palace and the adjoining winter garden. The intendant now informed Irma of his plan, and was delighted to find that she approved of it. At the end of the garden he intended to erect a large fountain, ornamented with antique groups. In the foreground he meant to have trees and shrubbery and various kinds of rocks, so that none could approach too closely; and the background was to be a Grecian landscape, painted in the grand style.

Irma promised to keep his secret. Suddenly she exclaimed, "We are all of us no better than lackeys and kitchen-maids. We are kept busy stewing, roasting, and cooking for weeks, in order to prepare a dish that may please their Majesties."

The intendant made no reply.

"Do you remember," continued Irma, "how, when we were at the lake, we spoke of the fact that man possessed the advantage of being able to change his dress, and thus to alter his appearance? While yet a child, masquerading was my greatest delight. The soul wings its flight in callow infancy. A bal costumé is indeed one of the noblest fruits of culture. The love of coquetry which is innate with all of us displays itself there undisguised."

The intendant took his leave. While walking away, his mind was filled with his old thoughts about Irma.

"No," said he to himself, "such a woman would be a constant strain, and would require one to be brilliant and intellectual all day long. She would exhaust one," said he, almost aloud.

No one knew what character Irma intended to appear in, although many supposed that it would be as "Victory," since it was well known that she had stood for the model of the statue that surmounted the arsenal. They were busy conjecturing how she could assume that character without violating the social proprieties.

Irma spent much of her time in the atelier, and worked assiduously. She was unable to escape a feeling of unrest, far greater than that she had experienced years ago when looking forward to her first ball. She could not reconcile herself to the idea of preparing for the fête so long beforehand, and would like to have had it take place in the very next hour, so that something else might be taken up at once. The long delay tried her patience. She almost envied those beings to whom the preparation for pleasure affords the greatest part of the enjoyment. Work alone calmed her unrest. She had something to do, and this prevented the thoughts of the festival from engaging her mind during the day. It was only in the evening that she would recompense herself for the day's work, by giving full swing to her fancy.

The statue of Victory was still in the atelier and was almost finished. High ladders were placed beside it. The artist was still chiseling at the figure, and would now and then hurry down to observe the general effect, and then hastily mount the ladder again in order to add a touch here or there. Irma scarcely ventured to look up at this effigy of herself in Grecian costume--transformed and yet herself. The idea of being thus translated into the purest of art's forms filled her with a tremor, half joy, half fear.

It was on a winter afternoon. Irma was working assiduously at a copy of a bust of Theseus, for it was growing dark. Near her stood her preceptor's marble bust of Doctor Gunther. All was silent; not a sound was heard save now and then the picking or scratching of the chisel.

At that moment the master descended the ladder, and drawing a deep breath, said:--

"There--that will do. One can never finish. I shall not put another stroke to it. I am afraid that retouching would only injure it. It is done."

In the master's words and manner, struggling effort and calm content seemed mingled. He laid the chisel aside. Irma looked at him earnestly and said:--

"You are a happy man; but I can imagine that you are still unsatisfied. I don't believe that even Raphael or Michael Angelo was ever satisfied with the work he had completed. The remnant of dissatisfaction which an artist feels at the completion of a work is the germ of a new creation."

The master nodded his approval of her words. His eyes expressed his thanks. He went to the water-tap and washed his hands. Then he placed himself near Irma and looked at her, while telling her that in every work an artist parts with a portion of his life; that the figure will never again inspire the same feelings that it did while in the workshop. Viewed from afar, and serving as an ornament, no regard would be had to the care bestowed upon details. But the artist's great satisfaction in his work is in having pleased himself; and yet no one can accurately determine how, or to what extent, a conscientious working up of details will influence the general effect.

While the master was speaking, the King was announced. Irma hurriedly spread a damp cloth over her clay model.

The King entered. He was unattended, and begged Irma not to allow herself to be disturbed in her work. Without looking up, she went on with her modeling. The King was earnest in his praise of the master's work.

"The grandeur that dwells in this figure will show posterity what our days have beheld. I am proud of such contemporaries."

Irma felt that the words applied to her as well. Her heart throbbed. The plaster which stood before her suddenly seemed to gaze at her with a strange expression.

"I should like to compare the finished work with the first models," said the king to the artist.

"I regret that the experimental models are in my small atelier. Does your Majesty wish me to have them brought here?"

"If you will be good enough to do so."

The master left. The King and Irma were alone. With rapid steps the King mounted the ladder, and exclaimed in a tremulous voice:--

"I ascend into heaven--I ascend to you. Irma, I kiss you, I kiss your image, and may this kiss forever rest upon those lips, enduring beyond all time. I kiss thee with the kiss of eternity." He stood aloft and kissed the lips of the statue. Irma could not help looking up, and just at that moment a slanting sunbeam fell on the King and on the face of the marble figure, making it glow as if with life.

Irma felt as if wrapped in a fiery cloud, bearing her away into eternity.

The King descended and placed himself beside her. His breathing was short and quick. She did not dare to look up; she stood as silent and as immovable as a statue. Then the King embraced her--and living lips kissed each other.

Translation of S.A. Stern.

THE NEW HOME AND THE OLD ONE

From 'On the Heights'

Hansei received various offers for his cottage, and was always provoked when it was spoken of as a 'tumble-down old shanty.' He always looked as if he meant to say, "Don't take it ill of me, good old house: the people only abuse you so that they may get you cheap." Hansei stood his ground. He would not sell his home for a penny less than it was worth; and besides that, he owned the fishing-right, which was also worth something. Grubersepp at last took the house off his hands, with the design of putting a servant of his, who intended to marry in the fall, in possession of the place.

All the villagers were kind and friendly to them,--doubly so since they were about to leave,--and Hansei said:--

"It hurts me to think that I must leave a single enemy behind me, I'd like to make it up with the innkeeper."

Walpurga agreed with him, and said that she would go along; that she had really been the cause of the trouble, and that if the innkeeper wanted to scold any one, he might as well scold her too.

Hansei did not want his wife to go along, but she insisted upon it.

It was in the last evening in August that they went up into the village. Their hearts beat violently while they drew near to the inn. There was no light in the room. They groped about the porch, but not a soul was to be seen. Dachsel and Wachsel, however, were making a heathenish racket. Hansei called out:

"Is there no one at home?"

"No. There's no one at home," answered a voice from the dark room.

"Well, then tell the host, when he returns, that Hansei and his wife were here, and that they came to ask him to forgive them if they've done him any wrong; and to say that they forgive him too, and wish him luck."

"A11 right: I'll tell him," said the voice. The door was again slammed to, and Dachsel and Wachsel began barking again.

Hansei and Walpurga returned homeward.

"Do you know who that was?" asked Hansei.

"Why, yes: 'twas the innkeeper himself."

"Well, we've done all we could."

They found it sad to part from all the villagers. They listened to the lovely tones of the bell which they had heard every hour since childhood. Although their hearts were full, they did not say a word about the sadness of parting. Hansei at last broke silence:--"Our new home isn't out of the world: we can often come here."

When they reached the cottage they found that nearly all of the villagers had assembled in order to bid them farewell, but every one added, "I'll see you again in the morning."

Grubersepp also came again. He had been proud enough before; but now he was doubly so, for he had made a man of his neighbor, or at all events had helped to do so. He did not give way to tender sentiment. He condensed all his knowledge of life into a few sentences, which he delivered himself of most bluntly.

"I only want to tell you," said he, "you'll have lots of servants now. Take my word for it, the best of them are good for nothing; but something may be made of them for all that. He who would have his servants mow well, must take the scythe in hand himself. And since you got your riches so quickly, don't forget the proverb: 'Light come, light go.' Keep steady, or it'll go ill with you."

He gave him much more good advice, and Hansei accompanied him all the way back to his house. With a silent pressure of the hand they took leave of each other.

The house seemed empty, for quite a number of chests and boxes had been sent in advance by a boat that was already crossing the lake. On the following morning two teams would be in waiting on the other side.

"So this is the last time that we go to bed in this house," said the mother. They were all fatigued with work and excitement, and yet none of them cared to go to bed. At last, however, they could not help doing so, although they slept but little.

The next morning they were up and about at an early hour. Having attired themselves in their best clothes, they bundled up the beds and carried them into the boat. The mother kindled the last fire on the hearth. The cows were led out and put into the boat, the chickens were also taken along in a coop, and the dog was constantly running to and fro.

The hour of parting had come.

The mother uttered a prayer, and then called all of them into the kitchen. She scooped up some water from the pail and poured it into the fire, with these words:--"May all that's evil be thus poured out and extinguished, and let those who light a fire after us find nothing but health in their home."

Hansei, Walpurga, and Gundel were each of them obliged to pour a ladleful of water into the fire, and the grandmother guided the child's hand while it did the same thing.

After they had all silently performed this ceremony, the grandmother prayed aloud:--

"Take from us, O Lord our God, all heartache and home-sickness and all trouble, and grant us health and a happy home where we next kindle our fire."

She was the first to cross the threshold. She had the child in her arms and covered its eyes with her hands while she called out to the others:--

"Don't look back when you go out."

"Just wait a moment," said Hansei to Walpurga when he found himself alone with her. "Before we cross this threshold for the last time, I've something to tell you. I must tell it. I mean to be a righteous man and to keep nothing concealed from you. I must tell you this, Walpurga. While you were away and Black Esther lived up yonder, I once came very near being wicked--and unfaithful--thank God, I wasn't. But it torments me to think that I ever wanted to be bad; and now, Walpurga, forgive me and God will forgive me, too. Now I've told you, and have nothing more to tell. If I were to appear before God this moment, I'd know of nothing more."

Walpurga embraced him, and sobbing, said, "You're my dear good husband!" and they crossed the threshold for the last time.

When they reached the garden, Hansei paused, looked up at the cherry-tree, and said:--

"And so you remain here. Won't you come with us? We've always been good friends, and spent many an hour together. But wait! I'll take you with me, after all," cried he, joyfully, "and I'll plant you in my new home."

He carefully dug out a shoot that was sprouting up from one of the roots of the tree. He stuck it in his hat-band, and went to join his wife at the boat.

From the landing-place on the bank were heard the merry sounds of fiddles, clarinets, and trumpets.

Hansei hastened to the landing-place. The whole village had congregated there, and with it the full band of music. Tailor Schneck's son, he who had been one of, the cuirassiers at the christening of the crown prince, had arranged and was now conducting the parting ceremonies. Schneck, who was scraping his bass-viol, was the first to see Hansei, and called out in the midst of the music:--

"Long live farmer Hansei and the one he loves best! Hip, hip, hurrah!"

The early dawn resounded with their cheers. There was a flourish of trumpets, and the salutes fired from several small mortars were echoed back from the mountains. The large boat in which their household furniture, the two cows, and the fowls were placed, was adorned with wreaths of fir and oak. Walpurga was standing in the middle of the boat, and with both hands held the child aloft, so that it might see the great crowd of friends and the lake sparkling in the rosy dawn.

"My master's best respects," said one of Grubersepp's servants, leading a snow-white colt by the halter: "he sends you this to remember him by."

Grubersepp was not present. He disliked noise and crowds. He was of a solitary and self-contained temperament. Nevertheless he sent a present which was not only of intrinsic value, but was also a most flattering souvenir; for a colt is usually given by a rich farmer to a younger brother when about to depart. In the eyes of all the world--that is to say, the whole village--Hansei appeared as the younger brother of Grubersepp.

Little Burgei shouted for joy when she saw them leading the snow-white foal into the boat. Gruberwaldl, who was but six years old, stood by the whinnying colt, stroking it and speaking kindly to it.

"Would you like to go to the farm with me and be my servant?" asked Hansei of Gruberwaldl.

"Yes, indeed, if you'll take me."

"See what a boy he is," said Hansei to his wife. "What a boy!"

Walpurga made no answer, but busied herself with the child.

Hansei shook hands with every one at parting. His hand trembled, but he did not forget to give a couple of crown thalers to the musicians.

At last he got into the boat and exclaimed:--

"Kind friends! I thank you all. Don't forget us, and we shan't forget you. Farewell! may God protect you all."

Walpurga and her mother were in tears.

"And now, in God's name, let us start!" The chains were loosened; the boat put off. Music, shouting, singing, and the firing of cannon resounded while the boat quietly moved away from the shore. The sun burst forth in all his glory.

The mother sat there, with her hands clasped. All were silent. The only sound heard was the neighing of the foal.

Walpurga was the first to break the silence. "O dear Lord! if people would only show each other half as much love during life as they do when one dies or moves away."

The grandmother, who was in the middle of a prayer, shook her head. She quickly finished her prayer and said:--

"That's more than one has the right to ask. It won't do to go about all day long with your heart in your hand. But remember, I've always told you that the people are good enough at heart, even if there are a few bad ones among them."

Hansei bestowed an admiring glance upon his wife, who had so many different thoughts about almost everything. He supposed it was caused by her having been away from home. But his heart was full, too, although in a different way.

"I can hardly realize," said Hansei, taking a long breath and putting the pipe, which he had intended to light, back into his pocket, "what has become of all the years that I spent there and all that I went through during the time. Look, Walpurga! the road you see there leads to my home. I know every hill and every hollow. My mother's buried there. Do you see the pines growing on the hill over yonder? That hill was quite bare; every tree was cut down when the French were here; and see how fine and hardy the trees are now. I planted most of them myself. I was a little boy about eleven or twelve years old when the forester hired me. He had fresh soil brought for the whole place and covered the rocky spots with moss. In the spring I worked from six in the morning till seven in the evening, putting in the little plants. My left hand was almost frozen, for I had to keep putting it into a tub of wet loam, with which I covered the roots. I was scantily clothed into the bargain, and had nothing to eat all day long but a piece of bread. In the morning it was cold enough to freeze the marrow in one's bones, and at noon I was almost roasted by the hot sun beating on the rocks. It was a hard life. Yes, I had a hard time of it when I was young. Thank God, it hasn't harmed me any. But I shan't forget it; and let's be right industrious and give all we can to the poor. I never would have believed that I'd live to call a single tree or a handful of earth my own; and now that God has given me so much, let's try and deserve it all."

Hansei's eyes blinked, as if there was something in them, and he pulled his hat down over his forehead. Now, while he was pulling himself up by the roots as it were, he could not help thinking of how thoroughly he had become engrafted into the neighborhood by the work of his hands and by habit. He had felled many a tree, but he knew full well how hard it was to remove the stumps.

The foal grew restive. Gruberwaldl, who had come with them in order to hold it, was not strong enough, and one of the boatmen was obliged to go to his assistance.

"Stay with the foal," said Hansei. "I'll take the oar."

"And I too," cried Walpurga. "Who knows when I'll have another chance? Ah! how often I've rowed on the lake with you and my blessed father."

Hansei and Walpurga sat side by side plying their oars in perfect time. It did them both good to have some employment which would enable them to work off the excitement.

"I shall miss the water," said Walpurga; "without the lake, life'll seem so dull and dry. I felt that, while I was in the city."

Hansei did not answer.

"At the summer palace there's a pond with swans swimming about in it," said she, but still received no answer. She looked around, and a feeling of anger arose within her. When she said anything at the palace, it was always listened to.

In a sorrowful tone she added, "It would have been better if we'd moved in the spring; it would have been much easier to get used to things."

"Maybe it would," replied Hansei, at last, "but I've got to hew wood in the winter. Walpurga, let's make life pleasant to each other, and not sad. I shall have enough on my shoulders, and can't have you and your palace thoughts besides."

Walpurga quickly answered, "I'll throw this ring, which the Queen gave me, into the lake, to prove that I've stopped thinking of the palace."

"There's no need of that. The ring's worth a nice sum, and besides that it's an honorable keepsake. You must do just as I do."

"Yes; only remain strong and true."

The grandmother suddenly stood up before them. Her features were illumined with a strange expression, and she said:--

"Children! Hold fast to the good fortune that you have. You've gone through fire and water together; for it was fire when you were surrounded by joy and love and every one greeted you with kindness--and you passed through the water, when the wickedness of others stung you to the soul. At that time the water was up to your neck, and yet you weren't drowned. Now you've got over it all. And when my last hour comes, don't weep for me; for through you I've enjoyed all the happiness a mother's heart can have in this world."

She knelt down, scooped up some water with her hand, and sprinkled it over Hansei's and also over Walpurga's face.

They rowed on in silence. The grandmother laid her head on a roll of bedding and closed her eyes. Her face wore a strange expression. After a while she opened her eyes again, and casting a glance full of happiness on her children, she said:

"Sing and be merry. Sing the song that father and I so often sang together; that one verse, the good one."

Hansei and Walpurga plied the oars while they sang:--

"Ah, blissful is the tender tie

That binds me, love, to thee;

And swiftly speed the hours by,

When thou art near to me."

They repeated the verse again, although at times the joyous shouting of the child and the neighing of the foal bade fair to interrupt it.

As they drew near the house, they could hear the neighing of the white foal.

"That's a good beginning," cried Hansei.

The grandmother placed the child on the ground, and got her hymn-book out of the chest. Pressing the book against her breast with both hands, she went into the house, being the first to enter. Hansei, who was standing near the stable, took a piece of chalk from his pocket and wrote the letters C.M.B., and the date, on the stable door. Then he too went into the house,--his wife, Irma, and the child following him.

Before going into the sitting-room the grandmother knocked thrice at the door. When she had entered she placed the open hymn-book upon the open window-sill, so that the sun might read in it. There were no tables or chairs in the room.

Hansei shook hands with his wife and said, "God be with you, freeholder's wife."

From that moment Walpurga was known as the "freeholder's wife," and was never called by any other name.

And now they showed Irma her room. The view extended over meadow and brook and the neighboring forest. She examined the room. There was naught but a green Dutch oven and bare walls, and she had brought nothing with her. In her paternal mansion, and at the castle, there were chairs and tables, horses and carriages; but here--None of these follow the dead.

Irma knelt by the window and gazed out over meadow and forest, where the sun was now shining.

How was it yesterday--was it only yesterday when you saw the sun go down?

Her thoughts were confused and indistinct. She pressed her hand to her forehead; the white handkerchief was still there. A bird looked up to her from the meadow, and when her glance rested upon it it flew away into the woods.

"The bird has its nest," said she to herself, "and I--"

Suddenly she drew herself up. Hansei had walked out to the grass plot in front of Irma's window, removed the slip of the cherry-tree from his hat, and planted it in the ground.

The grandmother stood by and said, "I trust that you'll be alive and hearty long enough to climb this tree and gather cherries from it, and that your children and grandchildren may do the same."

There was much to do and to set to rights in the house, and on such occasions it usually happens that those who are dearest to one another are as much in each other's way as closets and tables which have not yet been placed where they belong. The best proof of the amiability of these folks was that they assisted each other cheerfully, and indeed with jest and song.

Walpurga moved her best furniture into Irma's room. Hansei did not interpose a word. "Aren't you too lonely here?" asked Walpurga, after she had arranged everything as well as possible in so short a time.

"Not at all. There is no place in all the world lonely enough for me. You've so much to do now; don't worry about me. I must now arrange things within myself. I see how good you and yours are; fate has directed me kindly."

"Oh, don't talk in that way. If you hadn't given me the money, how could we have bought the farm? This is really your own."

"Don't speak of that," said Irma, with a sudden start. "Never mention that money to me again."

Walpurga promised, and merely added that Irma needn't be alarmed at the old man who lived in the room above hers, and who at times would talk to himself and make a loud noise. He was old and blind. The children teased and worried him, but he wasn't bad and would harm no one. Walpurga offered at all events to leave Gundel with Irma for the first night; but Irma preferred to be alone.

"You'll stay with us, won't you?" said Walpurga hesitatingly. "You won't have such bad thoughts again?"

"No, never. But don't talk now: my voice pains me, and so does yours too. Good-night! leave me alone."

Irma sat by the window and gazed out into the dark night. Was it only a day since she had passed through such terrors? Suddenly she sprang from her seat with a shudder. She had seen Black Esther's head rising out of the darkness, had again heard her dying shriek, had beheld the distorted face and the wild black tresses.--Her hair stood on end. Her thoughts carried her to the bottom of the lake, where she now lay dead. She opened the window and inhaled the soft, balmy air. She sat by the open casement for a long while, and suddenly heard some one laughing in the room above her.

"Ha! ha! I won't do you the favor! I won't die! I won't die! Pooh, pooh! I'll live till I'm a hundred years old, and then I'll get a new lease of life."

It was the old pensioner. After a while he continued:--

"I'm not so stupid; I know that it's night now, and the freeholder and his wife are come. I'll give them lots of trouble. I'm Jochem. Jochem's my name, and what the people don't like, I do for spite. Ha! ha! I don't use any light, and they must make me an allowance for that. I'll insist on it, if I have to go to the King himself about it."

Irma started when she heard the King mentioned.

"Yes, I'll go to the King, to the King! to the King!" cried the old man overhead, as if he knew that the word tortured Irma.

She heard him close the window and move a chair. The old man went to bed.

Irma looked out into the dark night. Not a star was to be seen. There was no light anywhere; nothing was heard but the roaring of the mountain stream and the rustling of the trees. The night seemed like a dark abyss.

"Are you still awake?" asked a soft voice without. It was the grandmother.

"I was once a servant at this farm," said she. "That was forty years ago; and now I'm the mother of the freeholder's wife, and almost the head one on the farm. But I keep thinking of you all the time. I keep trying to think how it is in your heart. I've something to tell you. Come out again. I'll take you where it'll do you good to be. Come!"

Irma went out into the dark night with the old woman. How different this guide from the one she had had the day before!

The old woman led her to the fountain. She had brought a cup with her and gave it to Irma. "Come, drink; good cold water's the best. Water comforts the body; it cools and quiets us; it's like bathing one's soul. I know what sorrow is too. One's insides burn as if they were afire."

Irma drank some of the water of the mountain spring. It seemed like a healing dew, whose influence was diffused through her whole frame.

The grandmother led her back to her room and said, "You've still got the shirt on that you wore at the palace. You'll never stop thinking of that place till you've burned that shirt."

The old woman would listen to no denial, and Irma was as docile as a little child. The grandmother hurried to get a coarse shirt for her, and after Irma had put it on, brought wood and a light and burnt the other at the open fire. Irma was also obliged to cut off her long nails and throw them into the fire. Then Beate disappeared for a few moments, and returned with Irma's riding-habit. "You must have been shot; for there are balls in this," said she, spreading out the long blue habit.

A smile passed over Irma's face, as she felt the balls that had been sewed into the lower part of the habit, so that it might hang more gracefully. Beate had also brought something very useful,--a deerskin. "Hansei sends you this," said she. "He thinks that maybe you're used to having something soft for your feet to rest on. He shot the deer himself."

Irma appreciated the kindness of the man who could show such affection to one who was both a stranger and a mystery to him.

The grandmother remained at Irma's bedside until she fell asleep. Then she breathed thrice on the sleeper and left the room.

It was late at night when Irma awoke.

"To the King! to the King! to the King!" The words had been uttered thrice in a loud voice. Was it hers, or that of the man overhead? Irma pressed her hand to her forehead and felt the bandage. Was it sea-grass that had gathered there? Was she lying alive at the bottom of the lake? Gradually all that had happened became clear to her.

Alone, in the dark and silent night, she wept. And these were the first tears she had shed since the terrible events through which she had passed.

It was evening when Irma awoke. She put her hand to her forehead. A wet cloth had been bound round it. She had been sleeping nearly twenty-four hours. The grandmother was sitting by her bed.

"You've a strong constitution," said the old woman, "and that helped you. It's all right now."

Irma arose. She felt strong, and guided by the grandmother, walked over to the dwelling-house.

"God be praised that you're well again," said Walpurga, who was standing there with her husband; and Hansei added, "yes, that's right."

Irma thanked them, and looked up at the gable of the house. What words there met her eye?

"Don't you think the house has a good motto written on its forehead?" asked Hansei.

Irma started. On the gable of the house she read the following inscription:--

EAT AND DRINK: FORGET NOT GOD: THINE HONOR GUARD:

OF ALL THY STORE,

THOU'LT CARRY HENCE

A WINDING-SHEET

AND NOTHING MORE.

Translation of S.A. Stern.

THE COURT PHYSICIAN'S PHILOSOPHY

From 'On the Heights'

Gunther continued, "I am only a physician, who has held many a hand hot with fever or stiff in death in his own. The healing art might serve as an illustration. We help all who need our help, and do not stop to ask who they are, whence they come, or whether when restored to health they persist in their evil courses. Our actions are incomplete, fragmentary; thought alone is complete and all-embracing. Our deeds and ourselves are but fragments--the whole is God."

"I think I grasp your meaning [replied the Queen]. But our life, as you say, is indeed a mere fraction of life as a whole; and how is each one to bear up under the portion of suffering that falls to his individual lot? Can one--I mean it in its best sense--always be outside of one's self?"

"I am well aware, your Majesty, that passions and emotions cannot be regulated by ideas; for they grow in a different soil, or, to express myself correctly, move in entirely different spheres. It is but a few days since I closed the eyes of my old friend Eberhard. Even he never fully succeeded in subordinating his temperament to his philosophy; but in his dying hour he rose beyond the terrible grief that broke his heart--grief for his child. He summoned the thoughts of better hours to his aid,--hours when his perception of the truth had been undimmed by sorrow or passion,--and he died a noble, peaceful death. Your Majesty must still live and labor, elevating yourself and others, at one and the same time. Permit me to remind you of the moment when, seated under the weeping ash, your heart was filled with pity for the poor child that from the time it enters into the world is doubly helpless. Do you still remember how you refused to rob it of its mother? I appeal to the pure and genuine impulse of that moment. You were noble and forgiving then, because you had not yet suffered. You cast no stone at the fallen; you loved, and therefore you forgave."

"O God!" cried the Queen, "and what has happened to me? The woman on whose bosom my child rested is the most abandoned of creatures. I loved her just as if she belonged to another world--a world of innocence. And now I am satisfied that she was the go-between, and that her naïveté was a mere mask concealing an unparalleled hypocrite. I imagined that truth and purity still dwelt in the simple rustic world--but everything is perverted and corrupt. The world of simplicity is base; aye, far worse than that of corruption!"

"I am not arguing about individuals. I think you mistaken in regard to Walpurga; but admitting that you are right, of this at least we can be sure: morality does not depend upon so-called education or ignorance, belief or unbelief. The heart and mind which have regained purity and steadfastness alone possess true knowledge. Extend your view beyond details and take in the whole--that alone can comfort and reconcile you."

"I see where you are, but I cannot get up there. I can't always be looking through your telescope that shows naught but blue sky. I am too weak. I know what you mean; you say in effect, 'Rise above these few people, above this span of space known as a kingdom: compared with the universe, they are but as so many blades of grass or a mere clod of earth.'"

Gunther nodded a pleased assent: but the Queen, in a sad voice, added:--

"Yes, but this space and these people constitute my world. Is purity merely imaginary? If it be not about us, where can it be found?"

"Within ourselves," replied Gunther. "If it dwell within us, it is everywhere; if not, it is nowhere. He who asks for more has not yet passed the threshold. His heart is not yet what it should be. True love for the things of this earth, and for God, the final cause of all, does not ask for love in return. We love the divine spark that dwells in creatures themselves unconscious of it: creatures who are wretched, debased, and as the church has it, unredeemed. My Master taught me that the purest joys arise from this love of God or of eternally pure nature. I made this truth my own, and you can and ought to do likewise. This park is yours; but the birds that dwell in it, the air, the light, its beauty, are not yours alone, but are shared with you by all. So long as the world is ours, in the vulgar sense of the word, we may love it; but when we have made it our own, in a purer and better sense, no one can take it from us. The great thing is to be strong and to know that hatred is death, that love alone is life, and that the amount of love that we possess is the measure of the life and the divinity that dwells within us."

Gunther rose and was about to withdraw. He feared lest excessive thought might over-agitate the Queen, who, however, motioned him to remain. He sat down again.

"You cannot imagine--" said the Queen after a long pause, "--but that is one of the cant phrases that we have learned by heart. I mean just the reverse of what I have said. You can imagine the change that your words have effected in me."

"I can conceive it."

"Let me ask a few more questions. I believe--nay, I am sure--that on the height you occupy, and toward which you would fain lead me, there dwells eternal peace. But it seems so cold and lonely up there. I am oppressed with a sense of fear, just as if I were in a balloon ascending into a rarer atmosphere, while more and more ballast was ever being thrown out. I don't know how to make my meaning clear to you. I don't understand how to keep up affectionate relations with those about me, and yet regard them from a distance, as it were,--looking upon their deeds as the mere action and reaction of natural forces. It seems to me as if, at that height, every sound and every image must vanish into thin air."

"Certainly, your Majesty. There is a realm of thought in which hearing and sight do not exist, where there is pure thought and nothing more."

"But are not the thoughts that there abound projected from the realm of death into that of life, and is that any better than monastic self-mortification?"

"It is just the contrary. They praise death, or at all events extol it, because after it life is to begin. I am not one of those who deny a future life. I only say, in the words of my Master, 'Our knowledge is of life and not of death,' and where my knowledge ceases my thoughts must cease. Our labors, our love, are all of this life. And because God is in this world and in all that exist in it, and only in those things, have we to liberate the divine essence wherever it exists. The law of love should rule. What the law of nature is in regard to matter, the moral law is to man."

"I cannot reconcile myself to your dividing the divine power into millions of parts. When a stone is crushed, every fragment still remains a stone; but when a flower is torn to pieces, the parts are no longer flowers."

"Let us take your simile as an illustration, although in truth no example is adequate. The world, the firmament, the creatures that live on the face of the earth, are not divided--they are one; thought regards them as a whole. Take for instance the flower. The idea of divinity which it suggests to us, and the fragrance which ascends from it, are yet part and parcel of the flower; attributes without which it is impossible for us to conceive of its existence. The works of all poets, all thinkers, all heroes, may be likened to streams of fragrance wafted through time and space. It is in the flower that they live forever. Although the eternal spirit dwells in the cell of every tree or flower and in every human heart, it is undivided and in its unity fills the world. He whose thoughts dwell in the infinite regards the world as the mighty corolla from which the thought of God exhales."

Translation of S.A. Stern.

IN COUNTESS IRMA'S DIARY

From 'On the Heights'

Yesterday was a year since I lay at the foot of the rock. I could not write a word. My brain whirled with the thoughts of that day; but now it is over.

I don't think I shall write much more. I have now experienced all the seasons in my new world. The circle is complete. There is nothing new to come from without. I know all that exists about me, or that can happen. I am at home in my new world.

Unto Jesus the Scribes and Pharisees brought a woman who was to be stoned to death, and He said unto them, "Let him that is without sin among you cast the first stone."

Thus it is written.

But I ask: How did she continue to live--she who was saved from being stoned to death; she who was pardoned--that is, condemned to live? How did she live on? Did she return to her home? How did she stand with the world? And how with her own heart?

No answer. None.

I must find the answer in my own experience

"Let him that is without sin among you cast the first stone." These are the noblest, the greatest words ever uttered by human lips, or heard by human ear. They divide the history of the human race into two parts. They are the "Let there be light" of the second creation. They divide and heal my little life too, and create me anew.

Has one who is not wholly without sin a right to offer precepts and reflections to others?

Look into your own heart. What are you?

Behold my hands. They are hardened by toil. I have done more than merely lift them in prayer.

Since I am alone I have not seen a letter of print. I have no book and wish for none; and this is not in order to mortify myself, but because I wish to be perfectly alone.

She who renounces the world, and in her loneliness still cherishes the thought of eternity, has assumed a heavy burden.

Convent life is not without its advantages. The different voices that join in the chorale sustain each other; and when the tone at last ceases, it seems to float away on the air and vanish by degrees. But here I am quite alone. I am priest and church, organ and congregation, confessor and penitent, all in one; and my heart is often so heavy, as if I must needs have another to help me bear the load. "Take me up and carry me, I cannot go further!" cries my soul. But then I rouse myself again, seize my scrip and my pilgrim's staff and wander on, solitary and alone; and while I wander, strength returns to me.

It often seems to me as if it were sinful thus to bury myself alive. My voice is no longer heard in song, and much more that dwells within me has become mute.

Is this right?

If my only object in life were to be at peace with myself, it would be well enough; but I long to labor and to do something for others. Yet where and what shall it be?

When I first heard that the beautifully carved furniture of the great and wealthy is the work of prisoners, it made me shudder. And now, although I am not deprived of freedom, I am in much the same condition. Those who have disfigured life should, as an act of expiation, help to make life more beautiful for others. The thought that I am doing this comforts and sustains me.

My work prospers. But last winter's wood is not yet fit for use. My little pitchman has brought me some that is old, excellent, and well seasoned, having been part of the rafters of an old house that has just been torn down. We work together cheerfully, and our earnings are considerable.

Vice is the same everywhere, except that here it is more open. Among the masses, vice is characterized by coarseness; among the upper classes, by meanness.

The latter shake off the consequences of their evil deeds, while the former are obliged to bear them.

The rude manners of these people are necessary, and are far preferable to polite deceit. They must needs be rough and rude. If it were not for its coarse, thick bark, the oak could not withstand the storm.

I have found that this rough bark covers more tenderness and sincerity than does the smoothest surface.

Jochem told me, to-day, that he is still quite a good walker, but that a blind man finds it very troublesome to go anywhere; for at every step he is obliged to grope about, so that he may feel sure of his ground before he firmly plants his foot on the earth.

Is it not the same with me? Am I not obliged to be sure of the ground before I take a step?

Such is the way of the fallen.

Ah! why does everything I see or hear become a symbol of my life?

I have now been here between two and three years. I have formed a resolve which it will be difficult to carry out. I shall go out into the world once more. I must again behold the scenes of my past life. I have tested myself severely.

May it not be a love of adventure, that genteel yet vulgar desire to undertake what is unusual or fraught with peril? Or is it a morbid desire to wander through the world after having died, as it were?

No; far from it. What can it be? An intense longing to roam again, if it be only for a few days. I must kill the desire, lest it kill me.

Whence arises this sudden longing?

Every tool that I use while at work burns my hand.

I must go.

I shall obey the impulse, without worrying myself with speculations as to its cause. I am subject to the rules of no order. My will is my only law. I harm no one by obeying it. I feel myself free; the world has no power over me.

I dreaded informing Walpurga of my intention. When I did so, her tone, her words, her whole manner, and the fact that she for the first time called me "child," made it seem as if her mother were still speaking to me.

"Child," said she, "you're right! Go! It'll do you good. I believe that you'll come back and will stay with us; but if you don't, and another life opens up to you--your expiation has been a bitter one, far heavier than your sin."

Uncle Peter was quite happy when he learned that we were to be gone from one Sunday to the Sunday following. When I asked him whether he was curious as to where we were going, he replied:--

"It's all one to me. I'd travel over the whole world with you, wherever you'd care to go; and if you were to drive me away, I'd follow you like a dog and find you again."

I shall take my journal with me, and will note down every day.

[By the lake.]--I find it difficult to write a word.

The threshold I am obliged to cross, in order to go out into the world, is my own gravestone.

I am equal to it.

How pleasant it was to descend toward the valley. Uncle Peter sang; and melodies suggested themselves to me, but I did not sing. Suddenly he interrupted himself and said:--

"In the inns you'll be my niece, won't you?"

"Yes."

"But you must call me 'uncle' when we're there?"

"Of course, dear uncle."

He kept nodding to himself for the rest of the way, and was quite happy.

We reached the inn at the landing. He drank, and I drank too, from the same glass.

"Where are you going?" asked the hostess.

"To the capital," said he, although I had not said a word to him about it. Then he said to me in a whisper:--

"If you intend to go elsewhere, the people needn't know everything."

I let him have his own way.

I looked for the place where I had wandered at that time. There--there was the rock--and on it a cross, bearing in golden characters the inscription:--

HERE PERISHED

IRMA, COUNTESS VON WILDENORT,

IN THE TWENTY-FIRST YEAR

OF HER LIFE.

Traveler, pray for her and honor her memory.

I never rightly knew why I was always dissatisfied, and yearning for the next hour, the next day, the next year, hoping that it would bring me that which I could not find in the present. It was not love, for love does not satisfy. I desired to live in the passing moment, but could not. It always seemed as if something were waiting for me without the door, and calling me. What could it have been?

I know now; it was a desire to be at one with myself, to understand myself. Myself in the world, and the world in me.

The vain man is the loneliest of human beings. He is constantly longing to be seen, understood, acknowledged, admired, and loved.

I could say much on the subject, for I too was once vain. It was only in actual solitude that I conquered the loneliness of vanity. It is enough for me that I exist.

How far removed this is from all that is mere show.

Now I understand my father's last act. He did not mean to punish me. His only desire was to arouse me; to lead me to self-consciousness; to the knowledge which, teaching us to become different from what we are, saves us.

I understand the inscription in my father's library:--"When I am alone, then am I least alone."

Yes; when alone, one can more perfectly lose himself in the life universal. I have lived and have come to know the truth. I can now die.

He who is at one with himself, possesses all....

I believe that I know what I have done. I have no compassion for myself. This is my full confession.

I have sinned--not against nature, but against the world's rules. Is that sin? Look at the tall pines in yonder forest. The higher the tree grows, the more do the lower branches die away; and thus the tree in the thick forest is protected and sheltered by its fellows, but can nevertheless not perfect itself in all directions.

I desired to lead a full and complete life and yet to be in the forest, to be in the world and yet in society. But he who means to live thus, must remain in solitude. As soon as we become members of society, we cease to be mere creatures of nature. Nature and morality have equal rights, and must form a compact with each other; and where there are two powers with equal rights, there must be mutual concessions.

Herein lies my sin.

He who desires to live a life of nature alone, must withdraw himself from the protection of morality. I did not fully desire either the one or the other; hence I was crushed and shattered.

My father's last action was right. He avenged the moral law, which is just as human as the law of nature. The animal world knows neither father nor mother, so soon as the young is able to take care of itself. The human world does know them and must hold them sacred.

I see it all quite clearly. My sufferings and my expiation are deserved. I was a thief! I stole the highest treasures of all: confidence, love, honor, respect, splendor.

How noble and exalted the tender souls appear to themselves when a poor rogue is sent to jail for having committed a theft! But what are all possessions which can be carried away, when compared with those that are intangible!

Those who are summoned to the bar of justice are not always the basest of mankind.

I acknowledge my sin, and my repentance is sincere.

My fatal sin, the sin for which I now atone, was that I dissembled, that I denied and extenuated that which I represented to myself as a natural right. Against the Queen I have sinned worst of all. To me she represents that moral order which I violated and yet wished to enjoy.

To you, O Queen, to you--lovely, good, and deeply injured one--do I confess all this!

If I die before you,--and I hope that I may,--these pages are to be given to you.

I can now accurately tell the season of the year, and often the hour of the day, by the way in which the first sunbeams fall into my room and on my work-bench in the morning. My chisel hangs before me on the wall, and is my index.

The drizzling spring showers now fall on the trees; and thus it is with me. It seems as if there were a new delight in store for me. What can it be? I shall patiently wait!

A strange feeling comes over me, as if I were lifted up from the chair on which I am sitting, and were flying, I know not whither! What is it? I feel as if dwelling in eternity.

Everything seems flying toward me: the sunlight and the sunshine, the rustling of the forests and the forest breezes, beings of all ages and of all kinds--all seem beautiful and rendered transparent by the sun's glow.

I am!

I am in God!

If I could only die now and be wafted through this joy to dissolution and redemption!

But I will live on until my hour comes.

Come, thou dark hour, whenever thou wilt! To me thou art light!

I feel that there is light within me. O Eternal Spirit of the universe, I am one with thee!

I was dead, and I live--I shall die and yet live.

Everything has been forgiven and blotted out.--There was dust on my wings.--I soar aloft into the sun and into infinite space. I shall die singing from the fullness of my soul. Shall I sing!

Enough.

I know that I shall again be gloomy and depressed and drag along a weary existence; but I have once soared into infinity and have felt a ray of eternity within me. That I shall never lose again. I should like to go to a convent, to some quiet, cloistered cell, where I might know nothing of the world, and could live on within myself until death shall call me. But it is not to be. I am destined to live on in freedom and to labor; to live with my fellow-beings and to work for them.

The results of my handiwork and of my powers of imagination belong to you; but what I am within myself is mine alone.

I have taken leave of everything here; of my quiet room, of my summer bench; for I know not whether I shall ever return. And if I do, who knows but what everything may have become strange to me?

(Last page written in pencil.)--It is my wish that when I am dead, I may be wrapped in a simple linen cloth, placed in a rough unplaned coffin, and buried under the apple-tree, on the road that leads to my paternal mansion. I desire that my brother and other relatives may be apprised of my death at once, and that they shall not disturb my grave by the wayside.

No stone, no name, is to mark my grave.

ÉMILE AUGIER

(1820-1889)

s an observer of society, a satirist, and a painter of types and characters of modern life, Émile Augier ranks among the greatest French dramatists of this century. Critics consider him in the line of direct descent from Molière and Beaumarchais. His collected works ('Theatre Complet') number twenty-seven plays, of which nine are in verse. Eight of these were written with a literary partner. Three are now called classics: 'Le Gendre de M. Poirier' (M. Poirier's Son-in-Law), 'L'Aventurière' (The Adventuress), and 'Fils de Giboyer' (Giboyer's Boy). 'Le Gendre de M. Poirier' was written with Jules Sandeau, but the admirers of Augier have proved by internal evidence that his share in its composition was the greater. It is a comedy of manners based on the old antagonism between vulgar ignorant energy and ability on the one side, and lazy empty birth and breeding on the other; embodied in Poirier, a wealthy shopkeeper, and M. de Presles, his son-in-law, an impoverished nobleman. Guillaume Victor Émile Augier was born in Valence, France, September 17th, 1820, and was intended for the law; but inheriting literary tastes from his grandfather, Pigault Lebrun the romance writer, he devoted himself to letters. When his first play, 'La Ciguë' (The Hemlock),--in the preface to which he defended his grandfather's memory,--was presented at the Odéon in 1844, it made the author famous. Théophile Gautier describes it at length in Vol. iii. of his 'Art Dramatique,' and compares it to Shakespeare's 'Timon of Athens.' It is a classic play, and the hero closes his career by a draught of hemlock.

Augier's works are:--'Un Homme de Bien' (A Good Man); 'L'Aventurière' (The Adventuress); 'Gabrielle'; 'Le Joueur de Flute' (The Flute Player); 'Diane' (Diana), a romantic play on the same theme as Victor Hugo's 'Marion Delorme,' written for and played by Rachel; 'La Pierre de Touche' (The Touchstone), with Jules Sandeau; 'Philberte,' a comedy of the last century; 'Le Mariage d'Olympe' (Olympia's Marriage); 'Le Gendre de M. Poirier' (M. Poirier's Son-in-Law); 'Ceinture Dorée' (The Golden Belt), with Edouard Foussier; 'La Jeunesse' (Youth); 'Les Lionnes Pauvres' (Ambition and Poverty),--a bold story of social life in Paris during the Second Empire, also with Foussier; 'Les Effrontés' (Brass), an attack on the worship of money; 'Le Fils de Giboyer' (Giboyer's Boy), the story of a father's devotion, ambitions, and self-sacrifice; 'Maître Guérin' (Guérin the Notary), the hero being an inventor; 'La Contagion' (Contagion), the theme of which is skepticism; 'Paul Forestier,' the story of a young artist; 'Le Post-Scriptum' (The Postscript); 'Lions et Renards' (Lions and Foxes), whose motive is love of power; 'Jean Thommeray,' the hero of which is drawn from Sandeau's novel of the same title; 'Madame Caverlet,' hinging on the divorce question; 'Les Fourchambault' (The Fourchambaults), a plea for family union; 'La Chasse au Roman' (Pursuit of a Romance), and 'L'Habit Vert' (The Green Coat), with Sandeau and Alfred de Musset; and the libretto for Gounod's opera 'Sappho.' Augier wrote one volume of verse, which he modestly called 'Pariétaire,' the name of a common little vine, the English danewort. In 1858 he was elected to the French Academy, and in 1868 became a Commander of the Legion of Honor. He died at Croissy, October 25th, 1889. An analysis of his dramas by Émile Montégut is published in the Revue de Deux Mondes for April, 1878.

A CONVERSATION WITH A PURPOSE

From 'Giboyer's Boy'

Marquis--Well, dear Baroness, what has an old bachelor like me done to deserve so charming a visit?

Baroness--That's what I wonder myself, Marquis. Now I see you I don't know why I've come, and I've a great mind to go straight back.

Marquis--Sit down, vexatious one!

Baroness--No. So you close your door for a week; your servants all look tragic; your friends put on mourning in anticipation; I, disconsolate, come to inquire--and behold, I find you at table!

Marquis--I'm an old flirt, and wouldn't show myself for an empire when I'm in a bad temper. You wouldn't recognize your agreeable friend when he has the gout;--that's why I hide.

Baroness--I shall rush off to reassure your friend.

Marquis--They are not so anxious as all that. Tell me something of them.

Baroness--But somebody's waiting in my carriage.

Marquis--I'll send to ask him up.

Baroness--But I'm not sure that you know him.

Marquis--His name?

Baroness--I met him by chance.

Marquis--And you brought him by chance. [He rings.] You are a mother to me. [To Dubois.] You will find an ecclesiastic in Madame's carriage. Tell him I'm much obliged for his kind alacrity, but I think I won't die this morning.

Baroness--O Marquis! what would our friends say if they heard you?

Marquis--Bah! I'm the black sheep of the party, its spoiled child; that's taken for granted. Dubois, you may say also that Madame begs the Abbé to drive home, and to send her carriage back for her.

Baroness--Allow me--

Marquis--Go along, Dubois.--Now you are my prisoner.

Baroness--But, Marquis, this is very unconventional.

Marquis [kissing her hand]--Flatterer! Now sit down, and let's talk about serious things. [Taking a newspaper from the table.] The gout hasn't kept me from reading the news. Do you know that poor Déodat's death is a serious mishap?

Baroness--What a loss to our cause!

Marquis--I have wept for him.

Baroness--Such talent! Such spirit! Such sarcasm!

Marquis--He was the hussar of orthodoxy. He will live in history as the angelic pamphleteer. And now that we have settled his noble ghost--

Baroness--You speak very lightly about it, Marquis.

Marquis--I tell you I've wept for him.--Now let's think of some one to replace him.

Baroness--Say to succeed him. Heaven doesn't create two such men at the same time.

Marquis--What if I tell you that I have found such another? Yes, Baroness, I've unearthed a wicked, cynical, virulent pen, that spits and splashes; a fellow who would lard his own father with epigrams for a consideration, and who would eat him with salt for five francs more.

Baroness--Déodat had sincere convictions.

Marquis--That's because he fought for them. There are no more mercenaries. The blows they get convince them. I'll give this fellow a week to belong to us body and soul.

Baroness--If you haven't any other proofs of his faithfulness--

Marquis--But I have.

Baroness--Where from?

Marquis--Never mind. I have it.

Baroness--And why do you wait before presenting him?

Marquis--For him in the first place, and then for his consent. He lives in Lyons, and I expect him to-day or to-morrow. As soon as he is presentable, I'll introduce him.

Baroness--Meanwhile, I'll tell the committee of your find.

Marquis--I beg you, no. With regard to the committee, dear Baroness, I wish you'd use your influence in a matter which touches me.

Baroness--I have not much influence--

Marquis--Is that modesty, or the exordium of a refusal?

Baroness--If either, it's modesty.

Marquis--Very well, my charming friend. Don't you know that these gentlemen owe you too much to refuse you anything?

Baroness--Because they meet in my parlor?

Marquis--That, yes; but the true, great, inestimable service you render every day is to possess such superb eyes.

Baroness--It's well for you to pay attention to such things!

Marquis--Well for me, but better for these Solons whose compliments don't exceed a certain romantic intensity.

Baroness--You are dreaming.

Marquis--What I say is true. That's why serious societies always rally in the parlor of a woman, sometimes clever, sometimes beautiful. You are both, Madame: judge then of your power!

Baroness--You are too complimentary: your cause must be detestable.

Marquis--If it was good I could win it for myself.

Baroness--Come, tell me, tell me.

Marquis--Well, then: we must choose an orator to the Chamber for our Campaign against the University. I want them to choose--

Baroness--Monsieur Maréchal?

Marquis--You are right.

Baroness--Do you really think so, Marquis? Monsieur Maréchal?

Marquis--Yes, I know. But we don't need a bolt of eloquence, since we'll furnish the address. Maréchal reads well enough, I assure you.

Baroness--We made him deputy on your recommendation. That was a good deal.