автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Library of the World's Best Literature, Ancient and Modern — Volume 1

E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Charlie Kirschner,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

LIBRARY OF THE

WORLD'S BEST LITERATURE

ANCIENT AND MODERN

VOL. I.

CHARLES DUDLEY WARNER

EDITOR

HAMILTON WRIGHT MABIE

LUCIA GILBERT RUNKLE

GEORGE HENRY WARNER

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Connoisseur Edition

PREFACE

he plan of this Work is simple, and yet it is novel. In its distinctive features it differs from any compilation that has yet been made. Its main purpose is to present to American households a mass of good reading. But it goes much beyond this. For in selecting this reading it draws upon all literatures of all time and of every race, and thus becomes a conspectus of the thought and intellectual evolution of man from the beginning. Another and scarcely less important purpose is the interpretation of this literature in essays by scholars and authors competent to speak with authority.

The title, "A Library of the World's Best Literature," is strictly descriptive. It means that what is offered to the reader is taken from the best authors, and is fairly representative of the best literature and of all literatures. It may be important historically, or because at one time it expressed the thought and feeling of a nation, or because it has the character of universality, or because the readers of to-day will find it instructive, entertaining, or amusing. The Work aims to suit a great variety of tastes, and thus to commend itself as a household companion for any mood and any hour. There is no intention of presenting merely a mass of historical material, however important it is in its place, which is commonly of the sort that people recommend others to read and do not read themselves. It is not a library of reference only, but a library to be read. The selections do not represent the partialities and prejudices and cultivation of any one person, or of a group of editors even; but, under the necessary editorial supervision, the sober judgment of almost as many minds as have assisted in the preparation of these volumes. By this method, breadth of appreciation has been sought.

The arrangement is not chronological, but alphabetical, under the names of the authors, and, in some cases, of literatures and special subjects. Thus, in each volume a certain variety is secured, the heaviness or sameness of a mass of antique, classical, or mediaeval material is avoided, and the reader obtains a sense of the varieties and contrasts of different periods. But the work is not an encyclopaedia, or merely a dictionary of authors. Comprehensive information as to all writers of importance may be included in a supplementary reference volume; but the attempt to quote from all would destroy the Work for reading purposes, and reduce it to a herbarium of specimens.

In order to present a view of the entire literary field, and to make these volumes especially useful to persons who have not access to large libraries, as well as to treat certain literatures or subjects when the names of writers are unknown or would have no significance to the reader, it has been found necessary to make groups of certain nationalities, periods, and special topics. For instance, if the reader would like to know something of ancient and remote literatures which cannot well be treated under the alphabetical list of authors, he will find special essays by competent scholars on the Accadian-Babylonian literature, on the Egyptian, the Hindu, the Chinese, the Japanese, the Icelandic, the Celtic, and others, followed by selections many of which have been specially translated for this Work. In these literatures names of ascertained authors are given in the Index. The intention of the essays is to acquaint the reader with the spirit, purpose, and tendency of these writings, in order that he may have a comparative view of the continuity of thought and the value of tradition in the world. Some subjects, like the Arthurian Legends, the Nibelungen Lied, the Holy Grail, Provençal Poetry, the Chansons and Romances, and the Gesta Romanorum, receive a similar treatment. Single poems upon which the authors' title to fame mainly rests, familiar and dear hymns, and occasional and modern verse of value, are also grouped together under an appropriate heading, with reference in the Index whenever the poet is known.

It will thus be evident to the reader that the Library is fairly comprehensive and representative, and that it has an educational value, while offering constant and varied entertainment. This comprehensive feature, which gives the Work distinction, is, however, supplemented by another of scarcely less importance; namely, the critical interpretive and biographical comments upon the authors and their writings and their place in literature, not by one mind, or by a small editorial staff, but by a great number of writers and scholars, specialists and literary critics, who are able to speak from knowledge and with authority. Thus the Library becomes in a way representative of the scholarship and wide judgment of our own time. But the essays have another value. They give information for the guidance of the reader. If he becomes interested in any selections here given, and would like a fuller knowledge of the author's works, he can turn to the essay and find brief observations and characterizations which will assist him in making his choice of books from a library.

The selections are made for household and general reading; in the belief that the best literature contains enough that is pure and elevating and at the same time readable, to satisfy any taste that should be encouraged. Of course selection implies choice and exclusion. It is hoped that what is given will be generally approved; yet it may well happen that some readers will miss the names of authors whom they desire to read. But this Work, like every other, has its necessary limits; and in a general compilation the classic writings, and those productions that the world has set its seal on as among the best, must predominate over contemporary literature that is still on its trial. It should be said, however, that many writers of present note and popularity are omitted simply for lack of space. The editors are compelled to keep constantly in view the wider field. The general purpose is to give only literature; and where authors are cited who are generally known as philosophers, theologians, publicists, or scientists, it is because they have distinct literary quality, or because their influence upon literature itself has been so profound that the progress of the race could not be accounted for without them.

These volumes contain not only or mainly the literature of the past, but they aim to give, within the limits imposed by such a view, an idea of contemporary achievement and tendencies in all civilized countries. In this view of the modern world the literary product of America and Great Britain occupies the largest space.

It should be said that the plan of this Work could not have been carried out without the assistance of specialists in many departments of learning, and of writers of skill and insight, both in this country and in Europe. This assistance has been most cordially given, with a full recognition of the value of the enterprise and of the aid that the Library may give in encouraging and broadening literary tastes. Perhaps no better service could be rendered the American public at this period than the offer of an opportunity for a comprehensive study of the older and the greater literatures of other nations. By this comparison it can gain a just view of its own literature, and of its possible mission in the world of letters.

THE ADVISORY COUNCIL

CRAWFORD H. TOY, A.M., LL.D.,

Professor of Hebrew,

HARVARD UNIVERSITY, Cambridge, Mass.

THOMAS R. LOUNSBURY, LL.D., L.H.D.,

Professor of English in the Sheffield Scientific School of

YALE UNIVERSITY, New Haven, Conn.

WILLIAM M. SLOANE, PH.D., L.H.D.,

Professor of History and Political Science,

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY, Princeton, N.J.

BRANDER MATTHEWS, A.M., LL.B.,

Professor of Literature,

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, New York City.

JAMES B. ANGELL, LL.D.,

President of the

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, Ann Arbor, Mich.

WILLARD FISKE, A.M., PH.D.,

Late Professor of the Germanic and Scandinavian Languages and Literatures,

CORNELL UNIVERSITY, Ithaca, N.Y.

EDWARD S. HOLDEN, A.M., LL.D.,

Director of the Lick Observatory, and Astronomer

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, Berkeley, Cal.

ALCÉE FORTIER, LIT.D.,

Professor of the Romance Languages,

TULANE UNIVERSITY, New Orleans, La.

WILLIAM P. TRENT, M.A.,

Dean of the Department of Arts and Sciences, and Professor of English and History,

UNIVERSITY OF THE SOUTH, Sewanee, Tenn.

PAUL SHOREY, PH.D.,

Professor of Greek and Latin Literature,

UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO, Chicago, Ill.

WILLIAM T. HARRIS, LL.D.,

United States Commissioner of Education,

BUREAU OF EDUCATION, Washington, D.C.

MAURICE FRANCIS EGAN, A.M., LL.D.,

Professor of Literature in the

CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA, Washington, D.C.

NOTE OF ACKNOWLEDGMENT

wing to the many changes in the assignment of topics and engaging of writers incident to so extended a publication as the Library of the World's Best Literature, the Editor finds it impossible, before the completion of the work, adequately to recognize the very great aid which he has received from a large number of persons. A full list of contributors will be given in one of the concluding volumes. He will expressly acknowledge also his debt to those who have assisted him editorially, or in other special ways, in the preparation of these volumes.

Both Editor and Publishers have endeavored to give full credit to every author quoted, and to accompany every citation with ample notice of copyright ownership. At the close of the work it is their purpose to express in a more formal way their sense of obligation to the many publishers who have so courteously given permission for this use of their property, and whose rights of ownership it is intended thoroughly to protect.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

VOL. I

ABÉLARD AND HÉLOISE (by Thomas Davidson) -- 1079-1142

Letter of Héloise to Abélard

Abélard's Answer to Héloise

Vesper Hymn of Abélard

EDMOND ABOUT -- 1828-1885

The Capture ('The King of the Mountains')

Hadgi-Stavros (same)

The Victim ('The Man with the Broken Ear')

The Man without a Country (same)

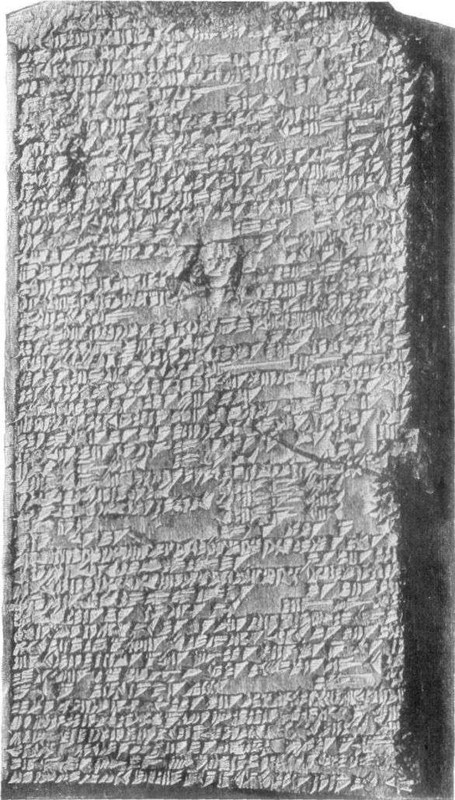

ACCADIAN-BABYLONIAN AND ASSYRIAN LITERATURE (by Crawford H. Toy)

Theogony

Revolt of Tiamat

Descent to the Underworld

The Flood

The Eagle and the Snake

The Flight of Etana

The God Zu

Adapa and the Southwind

Penitential Psalms

Inscription of Sennacherib

Invocation to the Goddess Beltis

Oracles of Ishtar of Arbela

An Erechite's Lament

ABIGAIL ADAMS (by Lucia Gilbert Runkle) -- 1744-1818

Letters--To her Husband:

May 24, 1775; June 15, 1775; June 18, 1775;

Nov. 27, 1775; April 20, 1777; June 8, 1779

To her Sister:

Sept. 5, 1784; May 10, 1785;

July 24, 1784; June 24, 1785

To her Niece

HENRY ADAMS -- 1838-

Auspices of the War of 1812

What the War of 1812 Demonstrated

Battle between the Constitution and the Guerrière

JOHN ADAMS -- 1735-1826

At the French Court ('Diary')

Character of Franklin (Letter to the Boston Patriot)

JOHN QUINCY ADAMS -- 1767-1848

Letter to his Father, at the Age of Ten

From the Memoirs, at the Age of Eighteen

From the Memoirs, Jan. 14, 1831; June 7, 1833; Sept. 9, 1833

The Mission of America (Fourth of July Oration, 1821)

The Right of Petition (Speech in Congress)

Nullification (Fourth of July Oration, 1831)

SARAH FLOWER ADAMS -- 1805-1848

He Sendeth Sun, He Sendeth Shower

Nearer, My God, to Thee

JOSEPH ADDISON (by Hamilton Wright Mabie) -- 1672-1720

Sir Roger de Coverley at the Play

Visit to Sir Roger de Coverley

Vanity of Human Life

Essay on Fans

Hymn, 'The Spacious Firmament'

AELIANUS CLAUDIUS -- Second Century

Of Certain Notable Men that made themselves Playfellowes with Children

Of a Certaine Sicilian whose Eyesight was Woonderfull Sharpe and Quick

The Lawe of the Lacedaemonians against Covetousness

That Sleep is the Brother of Death, and of Gorgias drawing to his End

Of the Voluntary and Willing Death of Calanus

Of Delicate Dinners, Sumptuous Suppers, and Prodigall Banqueting

Of Bestowing Time, and how Walking Up and Downe was not Allowable among the Lacedaemonians

How Socrates Suppressed the Pryde and Hautinesse of Alcibiades

Of Certaine Wastgoodes and Spendthriftes

AESCHINES -- B.C. 389-314

A Defense and an Attack ('Oration against Ctesiphon')

AESCHYLUS (by John Williams White) -- B.C. 525-456

Complaint of Prometheus ('Prometheus')

Prayer to Artemis ('The Suppliants')

Defiance of Eteocles ('The Seven against Thebes')

Vision of Cassandra ('Agamemnon')

Lament of the Old Nurse ('The Libation-Pourers')

Decree of Athena ('The Eumenides')

AESOP (by Harry Thurston Peck) -- Seventh Century B.C.

The Fox and the Lion

The Ass in the Lion's Skin

The Ass Eating Thistles

The Wolf in Sheep's Clothing

The Countryman and the Snake

The Belly and the Members

The Satyr and the Traveler

The Lion and the other Beasts

The Ass and the Little Dog

The Country Mouse and the City Mouse

The Dog and the Wolf

JEAN LOUIS RODOLPHE AGASSIZ -- 1807-1873

The Silurian Beach ('Geological Sketches')

Voices ('Methods of Study in Natural History')

Formation of Coral Reefs (same)

AGATHIAS -- A.D. 536-581

Apostrophe to Plutarch

GRACE AGUILAR -- 1816-1847

Greatness of Friendship ('Woman's Friendship')

Order of Knighthood ('The Days of Bruce')

Culprit and Judge ('Home Influence')

WILLIAM HARRISON AINSWORTH -- 1805-1882

Students of Paris ('Crichton')

MARK AKENSIDE -- 1721-1770

From the Epistle to Curio

Aspirations after the Infinite ('Pleasures of the Imagination')

On a Sermon against Glory

PEDRO ANTONIO DE ALARCÓN -- 1833-1891

A Woman Viewed from Without ('The Three-Cornered Hat')

How the Orphan Manuel gained his Sobriquet ('The Child of the Ball')

ALCAEUS -- Sixth Century B.C.

The Palace

A Banquet Song

An Invitation

The Storm

The Poor Fisherman

The State

Poverty

BALTÁZAR DE ALCÁZAR -- 1530?-1606

Sleep

The Jovial Supper

ALCIPHRON (by Harry Thurston Peck) -- Second Century

From a Mercenary Girl--Petala to Simalion

Pleasures of Athens--Euthydicus to Epiphanio

From an Anxious Mother--Phyllis to Thrasonides

From a Curious Youth--Philocomus to Thestylus

From a Professional Diner-out--Capnosphrantes to Aristomachus

Unlucky Luck--Chytrolictes to Patellocharon

ALCMAN -- Seventh Century B.C.

Poem on Night

LOUISA MAY ALCOTT -- 1832-1888

The Night Ward ('Hospital Sketches')

Amy's Valley of Humiliation ('Little Women')

Thoreau's Flute (Atlantic Monthly)

Song from the Suds ('Little Women')

ALCUIN (by William H. Carpenter) -- 735?-8o4

On the Saints of the Church at York ('Alcuin and the Rise of the Christian Schools')

Disputation between Pepin, the Most Noble and Royal Youth, and Albinus the Scholastic

A Letter from Alcuin to Charlemagne

HENRY M. ALDEN -- 1836-

A Dedication--To My Beloved Wife ('A Study of Death')

The Dove and the Serpent (same)

Death and Sleep (same)

The Parable of the Prodigal (same)

THOMAS BAILEY ALDRICH -- 1837-

Destiny

Identity

Prescience

Alec Yeaton's Son

Memory

Tennyson (1890)

Sweetheart, Sigh No More

Broken Music

Elmwood

Sea Longings

A Shadow of the Night

Outward Bound

Reminiscence

Père Antoine's Date-Palm

Miss Mehetabel's Son

ALEARDO ALEARDI -- 1812-1878

Cowards ('The Primal Histories')

The Harvesters ('Monte Circello')

The Death of the Year ('An Hour of My Youth')

JEAN LE ROND D'ALEMBERT -- 1717-1783

Montesquieu (Eulogy in the 'Encyclopédie')

VITTORIO ALFIERI (by L. Oscar Kuhns) -- 1749-1803

Scenes from 'Agamemnon'

ALFONSO THE WISE -- 1221-1284

What Meaneth a Tyrant, and How he Useth his Power ('Las Siete Partidas')

On the Turks, and Why they are So Called ('La Gran Conquista de Ultramar')

To the Month of Mary ('Cantigas')

ALFRED THE GREAT -- 849-901

King Alfred on King-Craft

Alfred's Preface to the Version of Pope Gregory's 'Pastoral Care'

From Boethius

Blossom Gatherings from St. Augustine

CHARLES GRANT ALLEN -- 1848-

The Coloration of Flowers ('The Colors of Flowers')

Among the Heather ('The Evolutionist at Large')

The Heron's Haunt ('Vignettes from Nature')

JAMES LANE ALLEN -- 1850-

A Courtship ('A Summer in Arcady')

Old King Solomon's Coronation ('Flute and Violin')

WILLIAM ALLINGHAM -- 1828-1889

The Ruined Chapel

The Winter Pear

O Spirit of the Summer-time

The Bubble

St. Margaret's Eve

The Fairies

Robin Redbreast

An Evening

Daffodil

Lovely Mary Donnelly

KARL JONAS LUDVIG ALMQUIST -- 1793-1866

Characteristics of Cattle

A New Undine (from 'The Book of the Rose')

God's War

JOHANNA AMBROSIUS -- 1854-

A Peasant's Thoughts

Struggle and Peace

Do Thou Love, Too!

Invitation

EDMONDO DE AMICIS -- 1846-

The Light ('Constantinople')

Resemblances (same)

Birds (same)

Cordova ('Spain')

The Land of Pluck ('Holland and Its People')

The Dutch Masters ('Holland and Its People')

HENRI FRÉDÉRIC AMIEL (by Richard Burton) -- 1821-1881

Extracts from Amiel's Journal:

Christ's Real Message

Duty

Joubert

Greeks vs. Moderns

Nature, and Teutonic and Scandinavian Poetry

Training of Children

Mozart and Beethoven

FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

VOLUME I.

The Book of the Dead (Colored Plate).

First English Printing (Fac-simile).

Assyrian Clay Tablet (Fac-simile).

John Adams (Portrait).

John Quincy Adams (Portrait).

Joseph Addison (Portrait).

Louis Agassiz (Portrait).

"Poetry" (Photogravure).

Vittorio Alfieri (Portrait).

"A Courtship" (Photogravure).

"A Dutch Girl" (Photogravure).

VIGNETTE PORTRAITS

Pierre Abélard.

Edmond About.

Abigail Adams.

Aeschines.

Aeschylus.

Aesop.

Grace Aguilar.

William Harrison Ainsworth.

Mark Akenside.

Alcaeus.

Louisa May Alcott.

Thomas Bailey Aldrich.

Jean le Rond D'Alembert.

Edmondo de Amicis.

Books are not absolutely dead things, but do contain a potency of life in them to be as active as that soul was whose progeny they are; nay, they do preserve as in a vial the purest efficacy and extraction of that living intellect that bred them. I know they are as lively, and as vigorously productive, as those fabulous dragon's teeth; and being sown up and down, may chance to spring up armed men. And yet on the other hand, unless wariness be used, as good almost kill a man as kill a good book: who kills a man kills a reasonable creature, God's image; but he who destroys a good book, kills reason itself, kills the image of God, as it were in the eye. Many a man lives a burden to the earth; but a good book is the precious life-blood of a master-spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life.

JOHN MILTON.

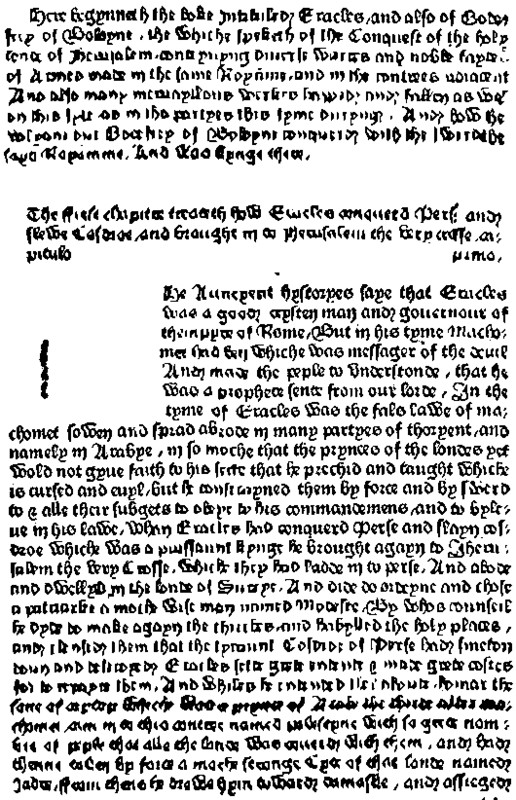

CAXTON.

Reduced facsimile of the first page of the only copy extant of

GODEFREY OF BOLOYNE

or

LAST SIEGE AND CONQUESTE OF JHERUSALEM.

The Prologue, at top of page, begins:

Here begynneth the boke Intituled Eracles, and also Godefrey of Boloyne,

the whiche speketh of the Conquest of the holy lande of Jherusalem.

Printed by Caxton, London, 1481. In the British Museum.

A good specimen page of the earliest English printing. Caxton's first

printed book, and the first book printed in English, was "The Game and

Play of the Chess," which was printed in 1474. The blank

space on this page was for the insertion by

hand of an illuminated initial T.

First English Printing (Fac-simile).

ABÉLARD

(1079--1142)

BY THOMAS DAVIDSON

ierre, the eldest son of Bérenger and Lucie (Abélard?) was born at Palais, near Nantes and the frontier of Brittany, in 1079. His knightly father, having in his youth been a student, was anxious to give his family, and especially his favorite Pierre, a liberal education. The boy was accordingly sent to school, under a teacher who at that time was making his mark in the world,--Roscellin, the reputed father of Nominalism. As the whole import and tragedy of his life may be traced back to this man's teaching, and the relation which it bore to the thought of the time, we must pause to consider these.

In the early centuries of our era, the two fundamental articles of the Gentile-Christian creed, the Trinity and the Incarnation, neither of them Jewish, were formulated in terms of Platonic philosophy, of which the distinctive tenet is, that the real and eternal is the universal, not the individual. On this assumption it was possible to say that the same real substance could exist in three, or indeed in any number of persons. In the case of God, the dogma-builders were careful to say, essence is one with existence, and therefore in Him the individuals are as real as the universal. Platonism, having lent the formula for the Trinity, became the favorite philosophy of many of the Church fathers, and so introduced into Christian thought and life the Platonic dualism, that sharp distinction between the temporal and the eternal which belittles the practical life and glorifies the contemplative.

This distinction, as aggravated by Neo-Platonism, further affected Eastern Christianity in the sixth century, and Western Christianity in the ninth, chiefly through the writings of (the pseudo-) Dionysius Areopagita, and gave rise to Christian mysticism. It was then erected into a rule of conduct through the efforts of Pope Gregory VII., who strove to subject practical and civil life entirely to the control of ecclesiastics and monks, standing for contemplative, supernatural life. The latter included all purely mental work, which more and more tended to concentrate itself upon religion and confine itself to the clergy. In this way it came to be considered an utter disgrace for any man engaged in mental work to take any part in the institutions of civil life, and particularly to marry. He might indeed enter into illicit relations, and rear a family of "nephews" and "nieces," without losing prestige; but to marry was to commit suicide. Such was the condition of things in the days of Abélard.

But while Platonism, with its real universals, was celebrating its ascetic, unearthly triumphs in the West, Aristotelianism, which maintains that the individual is the real, was making its way in the East. Banished as heresy beyond the limits of the Catholic Church, in the fifth and sixth centuries, in the persons of Nestorius and others, it took refuge in Syria, where it flourished for many years in the schools of Edessa and Nisibis, the foremost of the time. From these it found its way among the Arabs, and even to the illiterate Muhammad, who gave it (1) theoretic theological expression in the cxii. surah of the Koran: "He is One God, God the Eternal; He neither begets nor is begotten; and to Him there is no peer," in which both the fundamental dogmas of Christianity are denied, and that too on the ground of revelation; (2) practical expression, by forbidding asceticism and monasticism, and encouraging a robust, though somewhat coarse, natural life. Islam, indeed, was an attempt to rehabilitate the human.

In Abélard's time Arab Aristotelianism, with its consequences for thought and life, was filtering into Europe and forcing Christian thinkers to defend the bases of their faith. Since these, so far as defensible at all, depended upon the Platonic doctrine of universals, and this could be maintained only by dialectic, this science became extremely popular,--indeed, almost the rage. Little of the real Aristotle was at that time known in the West; but in Porphyry's Introduction to Aristotle's Logic was a famous passage, in which all the difficulties with regard to universals were stated without being solved. Over this the intellectual battles of the first age of Scholasticism were fought. The more clerical and mystic thinkers, like Anselm and Bernard, of course sided with Plato; but the more worldly, robust thinkers inclined to accept Aristotle, not seeing that his doctrine is fatal to the Trinity.

Prominent among these was a Breton, Roscellin, the early instructor of Abélard. From him the brilliant, fearless boy learnt two terrible lessons: (1) that universals, instead of being real substances, external and superior to individual things, are mere names (hence Nominalism) for common qualities of things as recognized by the human mind; (2) that since universals are the tools and criteria of thought, the human mind, in which alone these exist, is the judge of all truth,--a lesson which leads directly to pure rationalism, and indeed to the rehabilitation of the human as against the superhuman. No wonder that Roscellin came into conflict with the church authorities, and had to flee to England. Abélard afterwards modified his nominalism and behaved somewhat unhandsomely to him, but never escaped from the influence of his teaching. Abélard was a rationalist and an asserter of the human. Accordingly, when, definitely adopting the vocation of the scholar, he went to Paris to study dialectic under the then famous William of Champeaux, a declared Platonist, or realist as the designation then was, he gave his teacher infinite trouble by his subtle objections, and not seldom got the better of him.

These victories, which made him disliked both by his teacher and his fellow-pupils, went to increase his natural self-appreciation, and induced him, though a mere youth, to leave William and set up a rival school at Mélun. Here his splendid personality, his confidence, and his brilliant powers of reasoning and statement, drew to him a large number of admiring pupils, so that he was soon induced to move his school to Corbeil, near Paris, where his impetuous dialectic found a wider field. Here he worked so hard that he fell ill, and was compelled to return home to his family. With them he remained for several years, devoting himself to study,--not only of dialectic, but plainly also of theology. Returning to Paris, he went to study rhetoric under his old enemy, William of Champeaux, who had meanwhile, to increase his prestige, taken holy orders, and had been made bishop of Châlons. The old feud was renewed, and Abélard, being now better armed than before, compelled his master openly to withdraw from his extreme realistic position with regard to universals, and assume one more nearly approaching that of Aristotle.

This victory greatly diminished the fame of William, and increased that of Abélard; so that when the former left his chair and appointed a successor, the latter gave way to Abélard and became his pupil (1113). This was too much for William, who removed his successor, and so forced Abélard to retire again to Mélun. Here he remained but a short time; for, William having on account of unpopularity removed his school from Paris Abélard returned thither and opened a school outside the city, on Mont Ste. Généviève. William, hearing this, returned to Paris and tried to put him down, but in vain. Abélard was completely victorious.

After a time he returned once more to Palais, to see his mother, who was about to enter the cloister, as his father had done some time before. When this visit was over, instead of returning to Paris to lecture on dialectic, he went to Laon to study theology under the then famous Anselm. Here, convinced of the showy superficiality of Anselm, he once more got into difficulty, by undertaking to expound a chapter of Ezekiel without having studied it under any teacher. Though at first derided by his fellow-students, he succeeded so well as to draw a crowd of them to hear him, and so excited the envy of Anselm that the latter forbade him to teach in Laon. Abélard accordingly returned once more to Paris, convinced that he was fit to shine as a lecturer, not only on dialectic, but also on theology. And his audiences thought so also; for his lectures on Ezekiel were very popular and drew crowds. He was now at the height of his fame (1118).

The result of all these triumphs over dialecticians and theologians was unfortunate. He not only felt himself the intellectual superior of any living man, which he probably was, but he also began to look down upon the current thought of his time as obsolete and unworthy, and to set at naught even current opinion. He was now on the verge of forty, and his life had so far been one of spotless purity; but now, under the influence of vanity, this too gave way. Having no further conquests to make in the intellectual world, he began to consider whether, with his great personal beauty, manly bearing, and confident address, he might not make conquests in the social world, and arrived at the conclusion that no woman could reject him or refuse him her favor.

It was just at this unfortunate juncture that he went to live in the house of a certain Canon Fulbert, of the cathedral, whose brilliant niece, Héloïse, had at the age of seventeen just returned from a convent at Argenteuil, where she had been at school. Fulbert, who was proud of her talents, and glad to get the price of Abélard's board, took the latter into his house and intrusted him with the full care of Héloïse's further education, telling him even to chastise her if necessary. So complete was Fulbert's confidence in Abélard, that no restriction was put upon the companionship of teacher and pupil. The result was that Abélard and Héloïse, both equally inexperienced in matters of the heart, soon conceived for each other an overwhelming passion, comparable only to that of Faust and Gretchen. And the result in both cases was the same. Abélard, as a great scholar, could not think of marriage; and if he had, Héloïse would have refused to ruin his career by marrying him. So it came to pass that when their secret, never very carefully guarded, became no longer a secret, and threatened the safety of Héloïse, the only thing that her lover could do for her was to carry her off secretly to his home in Palais, and place her in charge of his sister. Here she remained until the birth of her child, which received the name of Astralabius, Abélard meanwhile continuing his work in Paris. And here all the nobility of his character comes out. Though Fulbert and his friends were, naturally enough, furious at what they regarded as his utter treachery, and though they tried to murder him, he protected himself, and as soon as Héloïse was fit to travel, hastened to Palais, and insisted upon removing her to Paris and making her his lawful wife. Héloïse used every argument which her fertile mind could suggest to dissuade him from a step which she felt must be his ruin, at the same time expressing her entire willingness to stand in a less honored relation to him. But Abélard was inexorable. Taking her to Paris, he procured the consent of her relatives to the marriage (which they agreed to keep secret), and even their presence at the ceremony, which was performed one morning before daybreak, after the two had spent a night of vigils in the church.

After the marriage, they parted and for some time saw little of each other. When Héloïse's relatives divulged the secret, and she was taxed with being Abélard's lawful wife, she "anathematized and swore that it was absolutely false." As the facts were too patent, however, Abélard removed her from Paris, and placed her in the convent at Argenteuil, where she had been educated. Here she assumed the garb of a novice. Her relatives, thinking that he must have done this in order to rid himself of her, furiously vowed vengeance, which they took in the meanest and most brutal form of personal violence. It was not a time of fine sensibilities, justice, or mercy; but even the public of those days was horrified, and gave expression to its horror. Abélard, overwhelmed with shame, despair, and remorse, could now think of nothing better than to abandon the world. Without any vocation, as he well knew, he assumed the monkish habit and retired to the monastery of St. Denis, while Héloïse, by his order, took the veil at Argenteuil. Her devotion and heroism on this occasion Abélard has described in touching terms. Thus supernaturalism had done its worst for these two strong, impetuous human souls.

If Abélard had entered the cloister in the hope of finding peace, he soon discovered his mistake. The dissolute life of the monks utterly disgusted him, while the clergy stormed him with petitions to continue his lectures. Yielding to these, he was soon again surrounded by crowds of students--so great that the monks at St. Denis were glad to get rid of him. He accordingly retired to a lonely cell, to which he was followed by more admirers than could find shelter or food. As the schools of Paris were thereby emptied, his rivals did everything in their power to put a stop to his teaching, declaring that as a monk he ought not to teach profane science, nor as a layman in theology sacred science. In order to legitimatize his claim to teach the latter, he now wrote a theological treatise, regarding which he says:--

"It so happened that I first endeavored to illuminate the basis of our faith by similitudes drawn from human reason, and to compose for our students a treatise on 'The Divine Unity and Trinity,' because they kept asking for human and philosophic reasons, and demanding rather what could be understood than what could be said, declaring that the mere utterance of words was useless unless followed by understanding; that nothing could be believed that was not first understood, and that it was ridiculous for any one to preach what neither he nor those he taught could comprehend, God himself calling such people blind leaders of the blind."

Here we have Abélard's central position, exactly the opposite to that of his realist contemporary, Anselm of Canterbury, whose principle was "Credo ut intelligam" (I believe, that I may understand). We must not suppose, however, that Abélard, with his rationalism, dreamed of undermining Christian dogma. Very far from it! He believed it to be rational, and thought he could prove it so. No wonder that the book gave offense, in an age when faith and ecstasy were placed above reason. Indeed, his rivals could have wished for nothing better than this book, which gave them a weapon to use against him. Led on by two old enemies, Alberich and Lotulf, they caused an ecclesiastical council to be called at Soissons, to pass judgment upon the book (1121). This judgment was a foregone conclusion, the trial being the merest farce, in which the pursuers were the judges, the Papal legate allowing his better reason to be overruled by their passion. Abélard was condemned to burn his book in public, and to read the Athanasian Creed as his confession of faith (which he did in tears), and then to be confined permanently in the monastery of St. Médard as a dangerous heretic.

His enemies seemed to have triumphed and to have silenced him forever. Soon after, however, the Papal legate, ashamed of the part he had taken in the transaction, restored him to liberty and allowed him to return to his own monastery at St. Denis. Here once more his rationalistic, critical spirit brought him into trouble with the bigoted, licentious monks. Having maintained, on the authority of Beda, that Dionysius, the patron saint of the monastery, was bishop of Corinth and not of Athens, he raised such a storm that he was forced to flee, and took refuge on a neighboring estate, whose proprietor, Count Thibauld, was friendly to him. Here he was cordially received by the monks of Troyes, and allowed to occupy a retreat belonging to them.

After some time, and with great difficulty, he obtained leave from the abbot of St. Denis to live where he chose, on condition of not joining any other order. Being now practically a free man, he retired to a lonely spot near Nogent-sur-Seine, on the banks of the Ardusson. There, having received a gift of a piece of land, he established himself along with a friendly cleric, building a small oratory of clay and reeds to the Holy Trinity. No sooner, however, was his place of retreat known than he was followed into the wilderness by hosts of students of all ranks, who lived in tents, slept on the ground, and underwent every kind of hardship, in order to listen to him (1123). These supplied his wants, and built a chapel, which he dedicated to the "Paraclete,"--a name at which his enemies, furious over his success, were greatly scandalized, but which ever after designated the whole establishment.

So incessant and unrelenting were the persecutions he suffered from those enemies, and so deep his indignation at their baseness, that for some time he seriously thought of escaping beyond the bounds of Christendom, and seeking refuge among the Muslim. But just then (1125) he was offered an important position, the abbotship of the monastery of St. Gildas-de-Rhuys, in Lower Brittany, on the lonely, inhospitable shore of the Atlantic. Eager for rest and a position promising influence, Abélard accepted the offer and left the Paraclete, not knowing what he was doing.

His position at St. Gildas was little less than slow martyrdom. The country was wild, the inhabitants were half barbarous, speaking a language unintelligible to him; the monks were violent, unruly, and dissolute, openly living with concubines; the lands of the monastery were subjected to intolerable burdens by the neighboring lord, leaving the monks in poverty and discontent. Instead of finding a home of God-fearing men, eager for enlightenment, he found a nest of greed and corruption. His attempts to introduce discipline, or even decency, among his "sons," only stirred up rebellion and placed his life in danger. Many times he was menaced with the sword, many times with poison. In spite of all that, he clung to his office, and labored to do his duty. Meanwhile the jealous abbot of St. Denis succeeded in establishing a claim to the lands of the convent at Argenteuil,--of which Héloïse, long since famous not only for learning but also for saintliness, was now the head,--and she and her nuns were violently evicted and cast on the world. Hearing of this with indignation, Abélard at once offered the homeless sisters the deserted Paraclete and all its belongings. The offer was thankfully accepted, and Héloïse with her family removed there to spend the remainder of her life. It does not appear that Abélard and Héloïse ever saw each other at this time, although he used every means in his power to provide for her safety and comfort. This was in 1129. Two years later the Paraclete was confirmed to Héloïse by a Papal bull. It remained a convent, and a famous one, for over six hundred years.

After this Abélard paid several visits to the convent, which he justly regarded as his foundation, in order to arrange a rule of life for its inmates, and to encourage them in their vocation. Although on these occasions he saw nothing of Héloïse, he did not escape the malignant suspicions of the world, nor of his own flock, which now became more unruly than ever,--so much so that he was compelled to live outside the monastery. Excommunication was tried in vain, and even the efforts of a Papal legate failed to restore order. For Abélard there was nothing but "fear within and conflict without." It was at this time, about 1132, that he wrote his famous 'Historia Calamitatum,' from which most of the above account of his life has been taken. In 1134, after nine years of painful struggle, he definitely left St. Gildas, without, however, resigning the abbotship. For the next two years he seems to have led a retired life, revising his old works and composing new ones.

Meanwhile, by some chance, his 'History of Calamities' fell into the hands of Héloïse at the Paraclete, was devoured with breathless interest, and rekindled the flame that seemed to have smoldered in her bosom for thirteen long years. Overcome with compassion for her husband, for such he really was, she at once wrote to him a letter which reveals the first healthy human heart-beat that had found expression in Christendom for a thousand years. Thus began a correspondence which, for genuine tragic pathos and human interest, has no equal in the world's literature. In Abélard, the scholarly monk has completely replaced the man; in Héloïse, the saintly nun is but a veil assumed in loving obedience to him, to conceal the deep-hearted, faithful, devoted flesh-and-blood woman. And such a woman! It may well be doubted if, for all that constitutes genuine womanhood, she ever had an equal. If there is salvation in love, Héloïse is in the heaven of heavens. She does not try to express her love in poems, as Mrs. Browning did; but her simple, straightforward expression of a love that would share Francesca's fate with her lover, rather than go to heaven without him, yields, and has yielded, matter for a hundred poems. She looks forward to no salvation; for her chief love is for him. Domino specialiter, sua singulariter: "As a member of the species woman I am the Lord's, as Héloïse I am yours"--nominalism with a vengeance!

But to return to Abélard. Permanent quiet in obscurity was plainly impossible for him; and so in 1136 we find him back at Ste. Généviève, lecturing to crowds of enthusiastic students. He probably thought that during the long years of his exile, the envy and hatred of his enemies had died out; but he soon discovered that he was greatly mistaken. He was too marked a character, and the tendency of his thought too dangerous, for that. Besides, he emptied the schools of his rivals, and adopted no conciliatory tone toward them. The natural result followed. In the year 1140, his enemies, headed by St. Bernard, who had long regarded him with suspicion, raised a cry of heresy against him, as subjecting everything to reason. Bernard, who was nothing if not a fanatic, and who managed to give vent to all his passions by placing them in the service of his God, at once denounced him to the Pope, to cardinals, and to bishops, in passionate letters, full of rhetoric, demanding his condemnation as a perverter of the bases of the faith.

At that time a great ecclesiastical council was about to assemble at Sens; and Abélard, feeling certain that his writings contained nothing which he could not show to be strictly orthodox, demanded that he should be allowed to explain and dialectically defend his position, in open dispute, before it. But this was above all things what his enemies dreaded. They felt that nothing was safe before his brilliant dialectic. Bernard even refused to enter the lists with him; and preferred to draw up a list of his heresies, in the form of sentences sundered from their context in his works,--some of them, indeed, from works which he never wrote,--and to call upon the council to condemn them. (These theses may be found in Denzinger's 'Enchiridion Symbolorum et Definitionum,' pp. 109 seq.) Abélard, clearly understanding the scheme, feeling its unfairness, and knowing the effect of Bernard's lachrymose pulpit rhetoric upon sympathetic ecclesiastics who believed in his power to work miracles, appeared before the council, only to appeal from its authority to Rome. The council, though somewhat disconcerted by this, proceeded to condemn the disputed theses, and sent a notice of its action to the Pope. Fearing that Abélard, who had friends in Rome, might proceed thither and obtain a reversal of the verdict, Bernard set every agency at work to obtain a confirmation of it before his victim could reach the Eternal City. And he succeeded.

The result was for a time kept secret from Abélard, who, now over sixty years old, set out on his painful journey. Stopping on his way at the famous, hospitable Abbey of Cluny, he was most kindly entertained by its noble abbot, who well deserved the name of Peter the Venerable. Here, apparently, he learned that he had been condemned and excommunicated; for he went no further. Peter offered the weary man an asylum in his house, which was gladly accepted; and Abélard, at last convinced of the vanity of all worldly ambition, settled down to a life of humiliation, meditation, study, and prayer. Soon afterward Bernard made advances toward reconciliation, which Abélard accepted; whereupon his excommunication was removed. Then the once proud Abélard, shattered in body and broken in spirit, had nothing more to do but to prepare for another life. And the end was not far off. He died at St. Marcel, on the 21st of April, 1142, at the age of sixty-three. His generous host, in a letter to Héloïse, gives a touching account of his closing days, which were mostly spent in a retreat provided for him on the banks of the Saône. There he read, wrote, dictated, and prayed, in the only quiet days which his life ever knew.

The body of Abélard was placed in a monolith coffin and buried in the chapel of the monastery of St. Marcel; but Peter the Venerable twenty-two years afterward allowed it to be secretly removed, and carried to the Paraclete, where Abélard had wished to lie. When Héloïse, world-famous for learning, virtue, and saintliness, passed away, and her body was laid beside his, he opened his arms and clasped her in close embrace. So says the legend, and who would not believe it? The united remains of the immortal lovers, after many vicissitudes, found at last (let us hope), in 1817, a permanent resting place, in the Parisian cemetery of Père Lachaise, having been placed together in Abélard's monolith coffin. "In death they were not divided."

Abélard's character may be summed up in a few words. He was one of the most brilliant and variously gifted men that ever lived, a sincere lover of truth and champion of freedom. But unfortunately, his extraordinary personal beauty and charm of manner made him the object of so much attention and adulation that he soon became unable to live without seeing himself mirrored in the admiration and love of others. Hence his restlessness, irritability, craving for publicity, fondness for dialectic triumph, and inability to live in fruitful obscurity; hence, too, his intrigue with Héloïse, his continual struggles and disappointments, his final humiliation and tragic end. Not having conquered the world, he cannot claim the crown of the martyr.

Abélard's works were collected by Cousin, and published in three 4to volumes (Paris, 1836, 1849, 1859). They include, besides the correspondence with Héloïse, and a number of sermons, hymns, answers to questions, etc., written for her, the following:--(1) 'Sic et Non,' a collection of (often contradictory) statements of the Fathers concerning the chief dogmas of religion, (2) 'Dialectic,' (3) 'On Genera and Species,' (4) Glosses to Porphyry's 'Introduction,' Aristotle's 'Categories and Interpretation,' and Boethius's 'Topics,' (5) 'Introduction to Theology,' (6) 'Christian Theology,' (7) 'Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans,' (9) 'Abstract of Christian Theology,' (10) 'Ethics, or Know Thyself,' (11) 'Dialogue between a Philosopher, a Jew, and a Christian,' (12) 'On the Intellects,' (12) 'On the Hexameron,' with a few short and unimportant fragments and tracts. None of Abélard's numerous poems in the vernacular, in which he celebrated his love for Héloïse, which he sang ravishingly (for he was a famous singer), and which at once became widely popular, seem to have come down to us; but we have a somewhat lengthy poem, of considerable merit (though of doubtful authenticity), addressed to his son Astralabius, who grew to manhood, became a cleric, and died, it seems, as abbot of Hauterive in Switzerland, in 1162.

Of Abélard's philosophy, little need be added to what has been already said. It is, on the whole, the philosophy of the Middle Age, with this difference: that he insists upon making theology rational, and thus may truly be called the founder of modern rationalism, and the initiator of the struggle against the tyrannic authority of blind faith. To have been so is his crowning merit, and is one that can hardly be overestimated. At the same time it must be borne in mind that he was a loyal son of the Church, and never dreamed of opposing or undermining her. His greatest originality is in 'Ethics,' in which, by placing the essence of morality in the intent and not in the action, he anticipated Kant and much modern speculation. Here he did admirable work. Abélard founded no school, strictly speaking; nevertheless, he determined the method and aim of Scholasticism, and exercised a boundless influence, which is not dead. Descartes and Kant are his children. Among his immediate disciples were a pope, twenty-nine cardinals, and more than fifty bishops. His two greatest pupils were Peter the Lombard, bishop of Paris, and author of the 'Sentences,' the theological text-book of the schools for hundreds of years; and Arnold of Brescia, one of the noblest champions of human liberty, though condemned and banished by the second Council of the Lateran.

The best biography of Abélard is that by Charles de Rémusat (2 vols., 8vo, Paris, 1845). See also, in English, Wight's 'Abelard and Eloise' (New York, 1853).

HÉLOÏSE TO ABÉLARD

A letter of yours sent to a friend, best beloved, to console him in affliction, was lately, almost by a chance, put into my hands. Seeing the superscription, guess how eagerly I seized it! I had lost the reality; I hoped to draw some comfort from this faint image of you. But alas!--for I well remember--every line was written with gall and wormwood.

How you retold our sorrowful history, and dwelt on your incessant afflictions! Well did you fulfill that promise to your friend, that, in comparison with your own, his misfortunes should seem but as trifles. You recalled the persecutions of your masters, the cruelty of my uncle, and the fierce hostility of your fellow-pupils, Albericus of Rheims, and Lotulphus of Lombardy--how through their plottings that glorious book your Theology was burned, and you confined and disgraced--you went on to the machinations of the Abbot of St. Denys and of your false brethren of the convent, and the calumnies of those wretches, Norbert and Bernard, who envy and hate you. It was even, you say, imputed to you as an offense to have given the name of Paraclete, contrary to the common practice, to the Oratory you had founded.

The persecutions of that cruel tyrant of St. Gildas, and of those execrable monks,--monks out of greed only, whom notwithstanding you call your children,--which still harass you, close the miserable history. Nobody could read or hear these things and not be moved to tears. What then must they mean to me?

We all despair of your life, and our trembling hearts dread to hear the tidings of your murder. For Christ's sake, who has thus far protected you,--write to us, as to His handmaids and yours, every circumstance of your present dangers. I and my sisters alone remain of all who were your friends. Let us be sharers of your joys and sorrows. Sympathy brings some relief, and a load laid on many shoulders is lighter. And write the more surely, if your letters may be messengers of joy. Whatever message they bring, at least they will show that you remember us. You can write to comfort your friend: while you soothe his wounds, you inflame mine. Heal, I pray you, those you yourself have made, you who bustle about to cure those for which you are not responsible. You cultivate a vineyard you did not plant, which grows nothing. Give heed to what you owe your own. You who spend so much on the obstinate, consider what you owe the obedient. You who lavish pains on your enemies, reflect on what you owe your daughters. And, counting nothing else, think how you are bound to me! What you owe to all devoted women, pay to her who is most devoted.

You know better than I how many treatises the holy fathers of the Church have written for our instruction; how they have labored to inform, to advise, and to console us. Is my ignorance to suggest knowledge to the learned Abélard? Long ago, indeed, your neglect astonished me. Neither religion, nor love of me, nor the example of the holy fathers, moved you to try to fix my struggling soul. Never, even when long grief had worn me down, did you come to see me, or send me one line of comfort,--me, to whom you were bound by marriage, and who clasp you about with a measureless love! And for the sake of this love have I no right to even a thought of yours?

You well know, dearest, how much I lost in losing you, and that the manner of it put me to double torture. You only can comfort me. By you I was wounded, and by you I must be healed. And it is only you on whom the debt rests. I have obeyed the last tittle of your commands; and if you bade me, I would sacrifice my soul.

To please you my love gave up the only thing in the universe it valued--the hope of your presence--and that forever. The instant I received your commands I quitted the habit of the world, and denied all the wishes of my nature. I meant to give up, for your sake, whatever I had once a right to call my own.

God knows it was always you, and you only that I thought of. I looked for no dowry, no alliance of marriage. And if the name of wife is holier and more exalted, the name of friend always remained sweeter to me, or if you would not be angry, a meaner title; since the more I gave up, the less should I injure your present renown, and the more deserve your love.

Nor had you yourself forgotten this in that letter which I recall. You are ready enough to set forth some of the reasons which I used to you, to persuade you not to fetter your freedom, but you pass over most of the pleas I made to withhold you from our ill-fated wedlock. I call God to witness that if Augustus, ruler of the world, should think me worthy the honor of marriage, and settle the whole globe on me to rule forever, it would seem dearer and prouder to me to be called your mistress than his empress.

Not because a man is rich or powerful is he better: riches and power may come from luck, constancy is from virtue. I hold that woman base who weds a rich man rather than a poor one, and takes a husband for her own gain. Whoever marries with such a motive--why, she will follow his prosperity rather than the man, and be willing to sell herself to a richer suitor.

That happiness which others imagine, best beloved, I experienced. Other women might think their husbands perfect, and be happy in the idea, but I knew that you were so and the universe knew the same. What philosopher, what king, could rival your fame? What village, city, kingdom, was not on fire to see you? When you appeared in public, who did not run to behold you? Wives and maidens alike recognized your beauty and grace. Queens envied Héloïse her Abélard.

Two gifts you had to lead captive the proudest soul, your voice that made all your teaching a delight, and your singing, which was like no other. Do you forget those tender songs you wrote for me, which all the world caught up and sang,--but not like you,--those songs that kept your name ever floating in the air, and made me known through many lands, the envy and the scorn of women?

What gifts of mind, what gifts of person glorified you! Oh, my loss! Who would change places with me now!

And you know, Abelard, that though I am the great cause of your misfortunes, I am most innocent. For a consequence is no part of a crime. Justice weighs not the thing done, but the intention. And how pure was my intention toward you, you alone can judge. Judge me! I will submit.

But how happens it, tell me, that since my profession of the life which you alone determined, I have been so neglected and so forgotten that you will neither see me nor write to me? Make me understand it, if you can, or I must tell you what everybody says: that it was not a pure love like mine that held your heart, and that your coarser feeling vanished with absence and ill-report. Would that to me alone this seemed so, best beloved, and not to all the world! Would that I could hear others excuse you, or devise excuses myself!

The things I ask ought to seem very small and easy to you. While I starve for you, do, now and then, by words, bring back your presence to me! How can you be generous in deeds if you are so avaricious in words? I have done everything for your sake. It was not religion that dragged me, a young girl, so fond of life, so ardent, to the harshness of the convent, but only your command. If I deserve nothing from you, how vain is my labor! God will not recompense me, for whose love I have done nothing.

When you resolved to take the vows, I followed,--rather, I ran before. You had the image of Lot's wife before your eyes; you feared I might look back, and therefore you deeded me to God by the sacred vestments and irrevocable vows before you took them yourself. For this, I own, I grieved, bitterly ashamed that I could depend on you so little, when I would lead or follow you straight to perdition. For my soul is always with you and no longer mine own. And if it is not with you in these last wretched years, it is nowhere. Do receive it kindly. Oh, if only you had returned favor for favor, even a little for the much, words for things! Would, beloved, that your affection would not take my tenderness and obedience always for granted; that it might be more anxious! But just because I have poured out all I have and am, you give me nothing. Remember, oh, remember how much you owe!

There was a time when people doubted whether I had given you all my heart, asking nothing. But the end shows how I began. I have denied myself a life which promised at least peace and work in the world, only to obey your hard exactions. I have kept back nothing for myself, except the comfort of pleasing you. How hard and cruel are you then, when I ask so little and that little is so easy for you to give!

In the name of God, to whom you are dedicate, send me some lines of consolation. Help me to learn obedience! When you wooed me because earthly love was beautiful, you sent me letter after letter. With your divine singing every street and house echoed my name! How much more ought you now to persuade to God her whom then you turned from Him! Heed what I ask; think what you owe. I have written a long letter, but the ending shall be short. Farewell, darling!

ABÉLARD'S ANSWER TO HÉLOÏSE

To Héloïse, his best beloved Sister in Christ,

Abélard, her Brother in Him:

If, since we resigned the world I have not written to you, it was because of the high opinion I have ever entertained of your wisdom and prudence. How could I think that she stood in need of help on whom Heaven had showered its best gifts? You were able, I knew, by example as by word, to instruct the ignorant, to comfort the timid, to kindle the lukewarm.

When prioress of Argenteuil, you practiced all these duties; and if you give the same attention to your daughters that you then gave to your sisters, it is enough. All my exhortations would be needless. But if, in your humility, you think otherwise, and if my words can avail you anything, tell me on what subjects you would have me write, and as God shall direct me I will instruct you. I thank God that the constant dangers to which I am exposed rouse your sympathies. Thus I may hope, under the divine protection of your prayers, to see Satan bruised under my feet.

Therefore I hasten to send you the form of prayer you beseech of me--you, my sister, once dear to me in the world, but now far dearer in Christ. Offer to God a constant sacrifice of prayer. Urge him to pardon our great and manifold sins, and to avert the dangers which threaten me. We know how powerful before God and his saints are the prayers of the faithful, but chiefly of faithful women for their friends, and of wives for their husbands. The Apostle admonishes us to pray without ceasing.... But I will not insist on the supplications of your sisterhood, day and night devoted to the service of their Maker; to you only do I turn. I well know how powerful your intercession may be. I pray you, exert it in this my need. In your prayers, then, ever remember him who, in a special sense, is yours. Urge your entreaties, for it is just that you should be heard. An equitable judge cannot refuse it.

In former days, you remember, best beloved, how fervently you recommended me to the care of Providence. Often in the day you uttered a special petition. Removed now from the Paraclete, and surrounded by perils, how much greater my need! Convince me of the sincerity of your regard, I entreat, I implore you.

[The Prayer:] "O God, who by Thy servant didst here assemble Thy handmaids in Thy Holy Name, grant, we beseech Thee, that he be protected from all adversity, and be restored safe to us, Thy handmaids."

If Heaven permit my enemies to destroy me, or if I perish by accident, see that my body is conveyed to the Paraclete. There, my daughters, or rather my sisters in Christ, seeing my tomb, will not cease to implore Heaven for me. No resting-place is so safe for the grieving soul, forsaken in the wilderness of its sins, none so full of hope as that which is dedicated to the Paraclete--that is, the Comforter.

Where could a Christian find a more peaceful grave than in the society of holy women, consecrated by God? They, as the Gospel tells us, would not leave their divine Master; they embalmed His body with precious spices; they followed Him to the tomb, and there they held their vigil. In return, it was to them that the angel of the resurrection appeared for their consolation.

Finally, let me entreat you that the solicitude you now too strongly feel for my life you will extend to the repose of my soul. Carry into my grave the love you showed me when alive; that is, never forget to pray Heaven for me.

Long life, farewell! Long life, farewell, to your sisters also! Remember me, but let it be in Christ!

Translated for the 'World's Best Literature.'

THE VESPER HYMN OF ABÉLARD

Oh, what shall be, oh, when shall be that holy Sabbath day,

Which heavenly care shall ever keep and celebrate alway,

When rest is found for weary limbs, when labor hath reward,

When everything forevermore is joyful in the Lord?

The true Jerusalem above, the holy town, is there,

Whose duties are so full of joy, whose joy so free from care;

Where disappointment cometh not to check the longing heart,

And where the heart, in ecstasy, hath gained her better part.

O glorious King, O happy state, O palace of the blest!

O sacred place and holy joy, and perfect, heavenly rest!

To thee aspire thy citizens in glory's bright array,

And what they feel and what they know they strive in vain to say.

For while we wait and long for home, it shall be ours to raise

Our songs and chants and vows and prayers in that dear country's praise;

And from these Babylonian streams to lift our weary eyes,

And view the city that we love descending from the skies.

There, there, secure from every ill, in freedom we shall sing

The songs of Zion, hindered here by days of suffering,

And unto Thee, our gracious Lord, our praises shall confess

That all our sorrow hath been good, and Thou by pain canst bless.

There Sabbath day to Sabbath day sheds on a ceaseless light,

Eternal pleasure of the saints who keep that Sabbath bright;

Nor shall the chant ineffable decline, nor ever cease,

Which we with all the angels sing in that sweet realm of peace.

Translation of Dr. Samuel W. Duffield.

EDMOND ABOUT

(1828-1885)

arly in the reign of Louis Napoleon, a serial story called 'Tolla,' a vivid study of social life in Rome, delighted the readers of the Revue des Deux Mondes. When published in book form in 1855 it drew a storm of opprobrium upon its young author, who was accused of offering as his own creation a translation of the Italian work 'Vittoria Savorelli.' This charge, undoubtedly unjust, he indignantly refuted. It served at least to make his name well known. Another book, 'La Question Romaine,' a brilliant if somewhat superficial argument against the temporal power of pope and priests, was a philosophic employment of the same material. Appearing in 1860, about the epoch of the French invasion of Austrian Italy, its tone agreed with popular sentiment and it was favorably received.

Edmond François Valentin About had a freakish, evasive, many-sided personality, a nature drawn in too many directions to achieve in any one of these the success his talents warranted. He was born in Dreuze, and like most French boys of literary ambition, soon found his way to Paris, where he studied at the Lycée Charlemagne. Here he won the honor prize; and in 1851 was sent to Athens to study archaeology at the École Française. He loved change and out-of-the-way experiences, and two studies resulted from this trip: 'La Grèce Contemporaine,' a book of charming philosophic description; and the delightful story 'Le Roi des Montagnes' (The King of the Mountains). This tale of the long-limbed German student, enveloped in the smoke from his porcelain pipe as he recounts a series of impossible adventures,--those of himself and two Englishwomen, captured for ransom by Hadgi Stavros, brigand king in the Grecian mountains,--is especially characteristic of About in the humorous atmosphere of every situation.

About wrote stories so easily and well that his early desertion of fiction is surprising. His mocking spirit has often suggested comparison with Voltaire, whom he studied and admired. He too is a skeptic and an idol-breaker; but his is a kindlier irony, a less incisive philosophy. Perhaps, however, this influence led to lack of faith in his own work, to his loss of an ideal, which Zola thinks the real secret of his sudden change from novelist to journalist. Voltaire taught him to scoff and disbelieve, to demand "à quoi bon?" and that took the heart out of him. He was rather fond of exposing abuses, a habit that appears in those witty letters to the Gaulois which in 1878 obliged him to suspend that journal. His was a positive mind, interested in political affairs, and with something always ready to say upon them. In 1872 he founded a radical newspaper, Le XIXme Siècle (The Nineteenth Century), in association with another aggressive spirit, that of Francisque Sarcey. For many years he proved his ability as editor, business man, and keen polemist.

He tried drama, too, inevitable ambition of young French authors; but after the failure of 'Guillery' at the Théâtre Française and 'Gaétena' at the Odéon, renounced the theatre. Indeed, his power is in odd conceptions, in the covert laugh and humorous suggestion of the phrasing, rather than in plot or characterization. He will always be best known for the tales and novels in that thoroughly French style--clear, concise, and witty--which in 1878 elected him president of the Société des Gens de Lettres, and in 1884 won him a seat in the Academy.

About wrote a number of novels, most of them as well known in translation to English and American readers as to his French audience. The bright stories originally published in the Moniteur, afterward collected with the title 'Les Mariages de Paris' had a conspicuous success, and were followed by a companion volume, 'Les Mariages de Province.' 'L'Homme à l'Oreille Cassée' (The Man with the Broken Ear)--the story of a mummy resuscitated to a world of new conditions after many years of apparent death--shows his freakish delight in oddity. So does 'Le Nez du Notaire' (The Notary's Nose), a gruesome tale of the tribulations of a handsome society man, whose nose is struck off in a duel by a revengeful Turk. The victim buys a bit of living skin from a poor water-carrier, and obtains a new nose by successful grafting. But he can nevermore get rid of the uncongenial Aquarius, who exercises occult influence over the skin with which he has parted. When he drinks too much, the Notary's nose is red; when he starves, it dwindles away; when he loses the arm from which the graft was made, the important feature drops off altogether, and the sufferer must needs buy a silver one. About's latest novel, 'Le Roman d'un Brave Homme' (The Story of an Honest Man), is in quite another vein, a charming picture of bourgeois virtue in revolutionary days. 'Madelon' and 'La Vielle Roche' (The Old School) are also popular.

French critics have not found much to say of this non-evolutionist of letters, who is neither pure realist nor pure romanticist, and who has no new theory of art. Some, indeed, may have scorned him for the wise taste which refuses to tread the debatable ground common to French fiction. But the reading public has received him with less conscious analysis, and has delighted in him. If he sees only what any clever man may see, and is no profound psychologist, yet he tells what he sees and what he imagines with delightful spirit and delightful wit, and tinges the fabric of his fancy with the ever-changing colors of his own versatile personality, fanciful suggestions, homely realism, and bright antithesis. Above all, he has the great gift of the story-teller.

THE CAPTURE

From 'The King of the Mountains'

"ST! ST!"

I raised my eyes. Two thickets of mastic-trees and arbutus enclosed the road on the right and left. From each tuft of trees protruded three or four musket-barrels. A voice cried out in Greek, "Seat yourselves on the ground!" This operation was the more easy to me, as my legs gave way under me. But I consoled myself by thinking that Ajax, Agamemnon, and the fiery Achilles, if they had found themselves in the same situation, would not have refused the seat that was offered.

The musket-barrels were leveled upon us. It seemed to me that they stretched out immeasurably, and that their muzzles were about to join above our heads. It was not that fear disturbed my vision; but I had never remarked so sensibly the desperate length of the Greek muskets! The whole arsenal soon debouched into the road, and every barrel showed its stock and its master.

The only difference which exists between devils and brigands is, that devils are less black than they are said to be, and brigands more dirty than people suppose. The eight bullies, who packed themselves in a circle around us, were so filthy in appearance that I should have wished to give them my money with a pair of tongs. You might guess, with a little effort, that their caps had been red; but lye-wash itself could not have restored the original color of their clothes. All the rocks of the kingdom had stained their cotton shirts, and their vests preserved a sample of the different soils on which they had reposed. Their hands, their faces, and even their moustachios were of a reddish-gray, like the soil which supports them. Every animal is colored according to its abode and its habits: the foxes of Greenland are of the color of snow; lions, of the desert; partridges, of the furrow; Greek brigands, of the highway.

The chief of the little troop which had made us prisoners was distinguished by no outward mark. Perhaps, however, his face, his hands, and his clothes were richer in dust than those of his comrades. He leaned toward us from the height of his tall figure, and examined us so closely that I felt the grazing of his moustachios. You would have pronounced him a tiger, who smells of his prey before tasting it. When his curiosity was satisfied, he said to Dimitri, "Empty your pockets!"

Dimitri did not give him cause to repeat the order: he threw down before him a knife, a tobacco-pouch, and three Mexican dollars, which compose a sum of about sixteen francs.

"Is that all?" demanded the brigand.

"Yes, brother."

"You are the servant?"

"Yes, brother."

"Take back one dollar. You must not return to the city without money."

Dimitri haggled. "You could well allow me two," said he: "I have two horses below; they are hired from the riding-school; I shall have to pay for the day."

"You will explain to Zimmerman that we have taken your money from you."

"And if he wishes to be paid, notwithstanding?"

"Answer that he is lucky enough to see his horses again."

"He knows very well that you do not take horses. What would you do with them in the mountains?"

"Enough! What is this big raw-boned animal next you?"

I answered for myself: "An honest German, whose spoils will not enrich you."

"You speak Greek well. Empty your pockets."

I deposited on the road a score of francs, my tobacco, my pipe, and my handkerchief.

"What is that?" asked the grand inquisitor.

"A handkerchief."

"For what purpose?"

"To wipe my nose."

"Why did you tell me that you were poor? It is only milords who wipe their noses with handkerchiefs. Take off the box which you have behind your back. Good! Open it!"

My box contained some plants, a book, a knife, a little package of arsenic, a gourd nearly empty, and the remnants of my breakfast, which kindled a look of covetousness in the eyes of Mrs. Simons. I had the assurance to offer them to her before my baggage changed masters. She accepted greedily, and began to devour the bread and meat. To my great astonishment, this act of gluttony scandalized our robbers, who murmured among themselves the word "Schismatic:" The monk made half a dozen signs of the cross, according to the rite of the Greek Church.

"You must have a watch," said the brigand: "put it with the rest."

I gave up my silver watch, a hereditary toy of the weight of four ounces. The villains passed it from hand to hand, and thought it very beautiful. I was in hopes that admiration, which makes men better, would dispose them to restore me something, and I begged their chief to let me have my tin box. He imposed silence upon me roughly. "At least," said I, "give me back two crowns for my return to the city!" He answered with a sardonic smile, "You will not have need of them."

The turn of Mrs. Simons had come. Before putting her hand in her pocket, she warned our conquerors in the language of her fathers. The English is one of those rare idioms which one can speak with a mouth full. "Reflect well on what you are going to do," said she, in a menacing tone. "I am an Englishwoman, and English subjects are inviolable in all the countries of the world. What you will take from me will serve you little, and will cost you dear. England will avenge me, and you will all be hanged, to say the least. Now if you wish my money, you have only to speak; but it will burn your fingers: it is English money!"

"What does she say?" asked the spokesman of the brigands.

Dimitri answered, "She says that she is English."

"So much the better! All the English are rich. Tell her to do as you have done."

The poor lady emptied on the sand a purse, which contained twelve sovereigns. As her watch was not in sight, and as they made no show of searching us, she kept it. The clemency of the conquerors left her her pocket-handkerchief.

Mary Ann threw down her watch, with a whole bunch of charms against the evil eye. She cast before her, by a movement full of mute grace, a shagreen bag, which she carried in her belt. The brigand opened it with the eagerness of a custom-house officer. He drew from it a little English dressing-case, a vial of English salts, a box of pastilles of English mint, and a hundred and some odd francs in English money.

"Now," said the impatient beauty, "you can let us go: we have nothing more for you." They indicated to her, by a menacing gesture, that the session was not ended. The chief of the band squatted down before our spoils, called "the good old man," counted the money in his presence, and delivered to him the sum of forty-five francs. Mrs. Simons nudged me on the elbow. "You see," said she, "the monk and Dimitri have betrayed us: he is dividing the spoils with them."

"No, madam," replied I, immediately. "Dimitri has received a mere pittance from that which they had stolen from him. It is a thing which is done everywhere. On the banks of the Rhine, when a traveler is ruined at roulette, the conductor of the game gives him something wherewith to return home."

"But the monk?"

"He has received a tenth part of the booty in virtue of an immemorial custom. Do not reproach him, but rather be thankful to him for having wished to save us, when his convent was interested in our capture."

This discussion was interrupted by the farewells of Dimitri. They had just set him at liberty.

"Wait for me," said I to him: "we will return together." He shook his head sadly, and answered me in English, so as to be understood by the ladies:-- "You are prisoners for some days, and you will not see Athens again before paying a ransom. I am going to inform the milord. Have these ladies any messages to give me for him?"

"Tell him," cried Mrs. Simons, "to run to the embassy, to go then to the Piraeus and find the admiral, to complain at the foreign office, to write to Lord Palmerston! They shall take us away from here by force of arms, or by public authority, but I do not intend that they shall disburse a penny for my liberty."

"As for me," replied I, without so much passion, "I beg you to tell my friends in what hands you have left me. If some hundreds of drachms are necessary to ransom a poor devil of a naturalist, they will find them without trouble. These gentlemen of the highway cannot rate me very high. I have a mind, while you are still here, to ask them what I am worth at the lowest price."

"It would be useless, my dear Mr. Hermann! It is not they who fix the figures of your ransom."

"And who then?"

"Their chief, Hadgi-Stavros."

HADGI-STAVROS

From 'The King of the Mountains'