автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Library of the World's Best Literature, Ancient and Modern, Vol. 16

LIBRARY OF THE

WORLD'S BEST LITERATURE

ANCIENT AND MODERN

CHARLES DUDLEY WARNER

EDITOR

HAMILTON WRIGHT MABIE

LUCIA GILBERT RUNKLE

GEORGE HENRY WARNER

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Connoisseur Edition

Vol. XVI.

NEW YORK

THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY

Connoisseur Edition

LIMITED TO FIVE HUNDRED COPIES IN HALF RUSSIA

No. ..........

Copyright, 1896, by

R. S. PEALE AND J. A. HILL

All rights reserved

THE ADVISORY COUNCIL

CRAWFORD H. TOY, A. M., LL. D.,

Professor of Hebrew, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

THOMAS R. LOUNSBURY, LL. D., L. H. D.,

Professor of English in the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

WILLIAM M. SLOANE, Ph. D., L. H. D.,

Professor of History and Political Science, Princeton University, Princeton, N. J.

BRANDER MATTHEWS, A. M., LL. B.,

Professor of Literature, Columbia University, New York City.

JAMES B. ANGELL, LL. D.,

President of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.

WILLARD FISKE, A. M., Ph. D.,

Late Professor of the Germanic and Scandinavian Languages and Literatures, Cornell University, Ithaca, N. Y.

EDWARD S. HOLDEN, A. M., LL. D.,

Director of the Lick Observatory, and Astronomer, University of California, Berkeley, Cal.

ALCÉE FORTIER, LIT. D.,

Professor of the Romance Languages, Tulane University, New Orleans, La.

WILLIAM P. TRENT, M. A.,

Dean of the Department of Arts and Sciences, and Professor of English and History, University of the South, Sewanee, Tenn.

PAUL SHOREY, Ph. D.,

Professor of Greek and Latin Literature, University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill.

WILLIAM T. HARRIS, LL. D.,

United States Commissioner of Education, Bureau of Education, Washington, D. C.

MAURICE FRANCIS EGAN, A. M., LL. D.,

Professor of Literature in the Catholic University of America, Washington, D. C.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

VOL. XVI

LIVED PAGE Aulus GelliusSecond Century A.D.

6253 From 'Attic Nights': Origin, and Plan of the Book; The Vestal Virgins; The Secrets of the Senate; Plutarch and his Slave; Discussion on One of Solon's Laws; The Nature of Sight; Earliest Libraries; Realistic Acting; The Athlete's End Gesta Romanorum 6261 Theodosius the Emperoure Moralite Ancelmus the Emperour Moralite How an Anchoress was Tempted by the Devil Edward Gibbon1737-1794

6271BY W. E. H. LECKY

Zenobia Foundation of Constantinople Character of Constantine Death of Julian Fall of Rome Silk Mahomet's Death and Character The Alexandrian Library Final Ruin of Rome All from the 'Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire' William Schwenck Gilbert1836-

6333 Captain Reece The Yarn of the Nancy Bell The Bishop of Rum-ti-foo Gentle Alice Brown The Captain and the Mermaids All from the 'Bab Ballads' Richard Watson Gilder1844-

6347 Two Songs from 'The New Day' "Rose-Dark the Solemn Sunset" The Celestial Passion Non Sine Dolore On the Life Mask of Abraham Lincoln From 'The Great Remembrance' Giuseppe Giusti1809-1850

6355 Lullaby ('Gingillino') The Steam Guillotine William Ewart Gladstone1809-

6359 Macaulay ('Gleanings of Past Years') Edwin Lawrence Godkin1831-

6373 The Duty of Criticism in a Democracy ('Problems of Modern Democracy') Goethe1749-1832

6385BY EDWARD DOWDEN

From 'Faust,' Shelley's Translation Scenes from 'Faust', Bayard Taylor's Translation Mignon's Love and Longing ('Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship') Wilhelm Meister's Introduction to Shakespeare (same) Wilhelm Meister's Analysis of Hamlet (same) The Indenture (same) The Harper's Songs (same) Mignon's Song (same) Philina's Song (same) Prometheus Wanderer's Night Songs The Elfin-King From 'The Wanderer's Storm Song' The Godlike Solitude Ergo Bibamus! Alexis and Dora Maxims and Reflections Nature Nikolai Vasilievitch Gogol1809-1852

6455BY ISABEL F. HAPGOOD

From 'The Inspector' Old-Fashioned Gentry ('Mirgorod') Carlo Goldoni1707-1793

6475BY WILLIAM CRANSTON LAWTON

First Love and Parting ('Memoirs of Carlo Goldoni') The Origin of Masks in the Italian Comedy (same) Purists and Pedantry (same) A Poet's Old Age (same) The Café Meïr Aaron Goldschmidt1819-1887

6493 Assar and Mirjam ('Love Stories from Many Countries') Oliver Goldsmith1728-1774

6501BY CHARLES MILLS GAYLEY

The Vicar's Family Become Ambitious ('The Vicar of Wakefield') New Misfortunes: But Offenses are Easily Pardoned Where There is Love at Bottom (same) Pictures from 'The Deserted Village' Contrasted National Types ('The Traveller') Ivan Aleksandrovitch Goncharóf1812-

6533BY NATHAN HASKELL DOLE

Oblómof The Brothers De Goncourt 6549Edmond

1822-1896

Jules

1830-1870

Two Famous Men ('Journal of the De Goncourts') The Suicide ('Sister Philomène') The Awakening ('Renée Mauperin') Edmund Gosse1849-

6565 February in Rome Desiderium Lying in the Grass Rudolf von Gottschall1823-

6571 Heinrich Heine ('Portraits and Studies') John Gower1325?-1408

6579 Petronella ('Confessio Amantis') Ulysses S. Grant1822-1885

6593BY HAMLIN GARLAND

Early Life ('Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant') Grant's Courtship (same) A Texan Experience (same) The Surrender of General Lee (same) Henry Grattan1746-1820

6615 On the Character of Chatham Of the Injustice of Disqualification of Catholics (Speech in Parliament) On the Downfall of Bonaparte (Speech in Parliament) Thomas Gray1716-1771

6623BY GEORGE PARSONS LATHROP

Elegy Written in a Country Church-yard Ode on the Spring On a Distant Prospect of Eton College The Bard The Greek Anthology 6637BY TALCOTT WILLIAMS

On the Athenian Dead at Platæa (Simonides); On the Lacedæmonian Dead at Platæa (Simonides); On a Sleeping Satyr (Plato); A Poet's Epitaph (Simmias of Thebes); Worship in Spring (Theætetus); Spring on the Coast (Leonidas of Tarentum); A Young Hero's Epitaph (Dioscorides); Love (Posidippus); Sorrow's Barren Grave (Heracleitus); To a Coy Maiden (Asclepiades); The Emptied Quiver (Mnesalcus); the Tale of Troy (Alpheus); Heaven Hath its Stars (Marcus Argentarius); Pan of the Sea-Cliff (Archias); Anacreon's Grave (Antipater of Sidon); Rest at Noon (Meleager); "In the Spring a Young Man's Fancy" (Meleager); Meleager's Own Epitaph (Meleager); Epilogue (Philodemus); Doctor and Divinity (Nicarchus); Love's Immortality (Strato); As the Flowers of the Field (Strato); Summer Sailing (Antiphilus); The Great Mysteries (Crinagoras); To Priapus of the Shore (Mæcius); The Common Lot (Ammianus); "To-morrow, and To-morrow" (Macedonius); The Palace Garden (Arabius); The Young Wife (Julianus Ægyptius); A Nameless Grave (Paulus Silentiarius); Resignation (Joannes Barbucallus); The House of the Righteous (Macedonius); Love's Ferriage (Agathias); On a Fowler (Isidorus). Anonymous: Youth and Riches; The Singing Reed; First Love again Remembered; Slave and Philosopher; Good-by to Childhood; Wishing; Hope and Experience; The Service of God; The Pure in Heart; The Water of Purity; Rose and Thorn; A Life's WanderingFULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

VOLUME XVI

PAGEThe Alexander Romance (Colored Plate)

Frontispiece

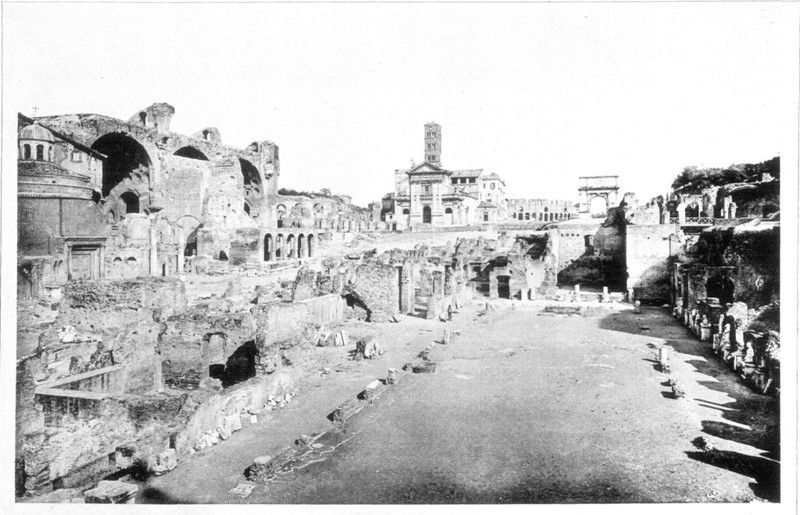

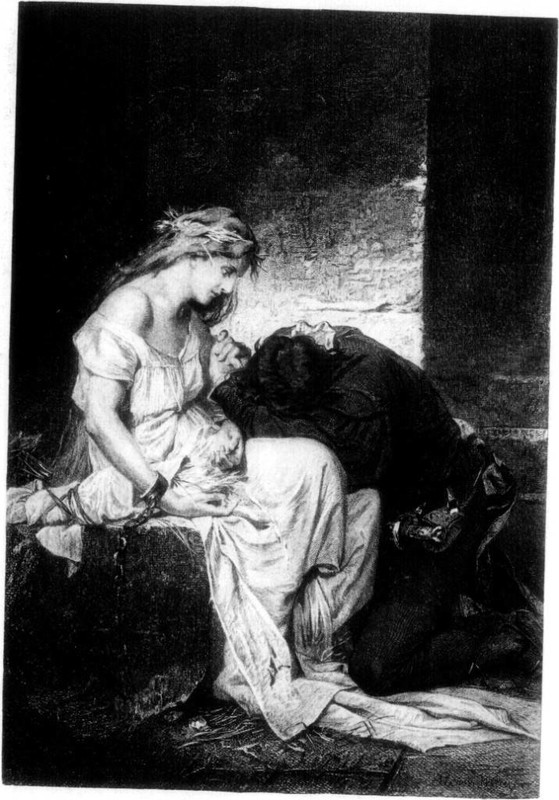

Gibbon (Portrait) 6271 Ruined Rome (Photograph) 6316 Gladstone (Portrait) 6359 Goethe (Portrait) 6385 "Faust and Margaret in Prison" (Photogravure) 6408"The Bride's Toilet" (Photogravure)

6466 Goldoni (Portrait) 6475 Goldsmith (Portrait) 6501 Grant (Portrait) 6593 Gray (Portrait) 6623 "Stoke Poges Church and Churchyard" (Photogravure) 6626VIGNETTE PORTRAITS

Gilbert Goncharof Gilder De Goncourt Giusti Gottschall Godkin Gower Gogol Grattan GoldschmidtAULUS GELLIUS

(Second Century A. D.)

erhaps Gellius's 'Attic Nights' may claim especial mention here, as one of the earliest extant forerunners of this 'Library.' In the original preface (given first among the citations), Gellius explains very clearly the origin and scope of his work. It is not, however, a mere scrap-book. There is original matter in many chapters. In particular, an ethical or philosophic excerpt has often been framed in a little scene,—doubtless imaginary,—and cast in the form of a dialogue. We get, even, pleasant glimpses of autobiography from time to time. The author is not, however, a deep or forceful character, on the whole. His heart is mostly set on trifles.

Yet Gellius has been an assiduous student, both in Greece and Italy; and his book gives us an agreeable, probably an adequate, view of the fields which are included in the general culture of his time. Despite its title, the work is chiefly Roman. In history, biography, antiquities, grammar, literary criticism, his materials and authors are prevailingly Latin. He is perhaps most widely known and quoted on early Roman life and usages. Thus, one of his chapters gives a mass of curious information as to the choice of the Vestal Virgins. We are also largely indebted to him for citations from lost authors. We have already quoted under Ennius the sketch, in eighteen hexameters, of a scholar-soldier, believed to be a genial self-portraiture. These lines are the finest specimen we have of the 'Annales.' Similarly, under Cato, we have quoted the chief fragment of the great Censor's Roman history. For both these treasures we must thank Gellius. Indeed, throughout the wide fields of Roman antiquities, history of literature, grammar, etc., we have to depend chiefly upon various late Latin scrap-books and compilations, most of which are not even made up at first hand from creative classical authors. To Gellius, also, the imposing array of writers so constantly named by him was evidently known chiefly through compendiums and handbooks. It is suspicious, for instance, that he hardly quotes a poet within a century of his own time. Repetitions, contradictions, etc., are numerous.

Despite its twenty "books" and nearly four hundred (short) chapters, the work is not only light and readable for the most part, but quite modest in total bulk: five hundred and fifty pages in the small page and generous type of Hertz's Teubner text. There is an English translation by Rev. W. Beloe, first printed in 1795, from which we quote below. Professor Nettleship's (in his 'Essays in Latin Literature') has no literary quality, but gives a careful analysis of Gellius's subjects and probable sources. There is a revival of interest in this author in recent years. We decidedly recommend Hertz's attractive volume to any Latin student who wishes to browse beyond the narrow classical limits.

FROM 'ATTIC NIGHTS'

Origin and Plan of the Book

More pleasing works than the present may certainly be found: my object in writing this was to provide my children, as well as myself, with that kind of amusement in which they might properly relax and indulge themselves at the intervals from more important business. I have preserved the same accidental arrangement which I had before used in making the collection. Whatever book came into my hand, whether it was Greek or Latin, or whatever I heard that was either worthy of being recorded or agreeable to my fancy, I wrote down without distinction and without order. These things I treasured up to aid my memory, as it were by a store-house of learning; so that when I wanted to refer to any particular circumstance or word which I had at the moment forgotten, and the books from which they were taken happened not to be at hand, I could easily find and apply it. Thus the same irregularity will appear in these commentaries as existed in the original annotations, which were concisely written down without any method or arrangement in the course of what I at different times had heard or read. As these observations at first constituted my business and my amusement through many long winter nights which I spent in Attica, I have given them the name of 'Attic Nights.' ... It is an old proverb, "A jay has no concern with music, nor a hog with perfumes:" but that the ill-humor and invidiousness of certain ill-taught people may be still more exasperated, I shall borrow a few verses from a chorus of Aristophanes; and what he, a man of most exquisite humor, proposed as a law to the spectators of his play, I also recommend to the readers of this volume, that the vulgar and unhallowed herd, who are averse to the sports of the Muses, may not touch nor even approach it. The verses are these:—

Chief—How do I feel? I'm not afraid; and yet I am,—a little. The merchants and citizens cause me some anxiety. They say I have been hard with them; but God knows, if I have ever taken anything from them it was not out of malice. I even think [takes him by the arm and leads him aside]—I even think there may be a sort of complaint against me. Why, in fact, is the Inspector coming to us? Listen, Ivan Kusmitch: why can't you—for our common good, you know—open every letter which passes through your office, going or coming, and read it, to see whether it contains a complaint or is simply correspondence? If it does not, then you can seal it up again. Besides, you could even deliver the letter unsealed.

Silent be they, and far from hence remove, By scenes like ours not likely to improve, Who never paid the honored Muse her rights, Who senseless live in wild, impure delights; I bid them once, I bid them twice begone, I bid them thrice, in still a louder tone: Far hence depart, whilst ye with dance and song Our solemn feast, our tuneful nights prolong.

The Vestal Virgins

The writers on the subject of taking a Vestal Virgin, of whom Labeo Antistius is the most elaborate, have asserted that no one could be taken who was less than six or more than ten years old. Neither could she be taken unless both her father and mother were alive, if she had any defect of voice or hearing, or indeed any personal blemish, or if she herself or father had been made free; or if under the protection of her grandfather, her father being alive; if one or both of her parents were in actual servitude, or employed in mean occupations. She whose sister was in this character might plead exemption, as might she whose father was flamen, augur, one of the fifteen who had care of the sacred books, or one of the seventeen who regulated the sacred feasts, or a priest of Mars. Exemption was also granted to her who was betrothed to a pontiff, and to the daughter of the sacred trumpeter. Capito Ateius has also observed that the daughter of a man was ineligible who had no establishment in Italy, and that his daughter might be excused who had three children. But as soon as a Vestal Virgin is taken, conducted to the vestibule of Vesta, and delivered to the pontiffs, she is from that moment removed from her father's authority, without any form of emancipation or loss of rank, and has also the right of making her will. No more ancient records remain concerning the form and ceremony of taking a virgin, except that the first virgin was taken by King Numa. But we find a Papian law which provides that at the will of the supreme pontiff twenty virgins should be chosen from the people; that these should draw lots in the public assembly; and that the supreme pontiff might take her whose lot it was, to become the servant of Vesta. But this drawing of lots by the Papian law does not now seem necessary; for if any person of ingenuous birth goes to the pontiff and offers his daughter for this ministry, if she may be accepted without any violation of what the ceremonies of religion enjoin, the Senate dispenses with the Papian law. Moreover, a virgin is said to be taken, because she is taken by the hand of the high priest from that parent under whose authority she is, and led away as a captive in war. In the first book of Fabius Pictor, we have the form of words which the supreme pontiff is to repeat when he takes a virgin. It is this:—

"I take thee, beloved, as a priestess of Vesta, to perform religious service, to discharge those duties with respect to the whole body of the Roman people which the law most wisely requires of a priestess of Vesta."

It is also said in those commentaries of Labeo which he wrote on the Twelve Tables:—

"No Vestal Virgin can be heiress to any intestate person of either sex. Such effects are said to belong to the public. It is inquired by what right this is done?" When taken she is called amata, or beloved, by the high priest; because Amata is said to have been the name of her who was first taken.

The Secrets of the Senate

It was formerly usual for the senators of Rome to enter the Senate-house accompanied by their sons who had taken the prætexta. When something of superior importance was discussed in the Senate, and the further consideration adjourned to the day following, it was resolved that no one should divulge the subject of their debates till it should be formally decreed. The mother of the young Papirius, who had accompanied his father to the Senate-house, inquired of her son what the senators had been doing. The youth replied that he had been enjoined silence, and was not at liberty to say. The woman became more anxious to know; the secretness of the thing, and the silence of the youth, did but inflame her curiosity. She therefore urged him with more vehement earnestness. The young man, on the importunity of his mother, determined on a humorous and pleasant fallacy: he said it was discussed in the Senate, which would be most beneficial to the State—for one man to have two wives, or for one woman to have two husbands. As soon as she heard this she was much agitated, and leaving her house in great trepidation, went to tell the other matrons what she had learned. The next day a troop of matrons went to the Senate-house, and with tears and entreaties implored that one woman might be suffered to have two husbands, rather than one man to have two wives. The senators on entering the house were astonished, and wondered what this intemperate proceeding of the women, and their petition, could mean. The young Papirius, advancing to the midst of the Senate, explained the pressing importunity of his mother, his answer, and the matter as it was. The Senate, delighted with the honor and ingenuity of the youth, made a decree that from that time no youth should be suffered to enter the Senate with his father, this Papirius alone excepted.

Plutarch and His Slave

Plutarch once ordered a slave, who was an impudent and worthless fellow, but who had paid some attention to books and philosophical disputations, to be stripped (I know not for what fault) and whipped. As soon as his punishment began, he averred that he did not deserve to be beaten; that he had been guilty of no offense or crime. As they went on whipping him, he called out louder, not with any cry of suffering or complaint, but gravely reproaching his master. Such behavior, he said, was unworthy of Plutarch; that anger disgraced a philosopher; that he had often disputed on the mischiefs of anger; that he had written a very excellent book about not giving place to anger; but that whatever he had said in that book was now contradicted by the furious and ungovernable anger with which he had now ordered him to be severely beaten. Plutarch then replied with deliberate calmness:—"But why, rascal, do I now seem to you to be in anger? Is it from my countenance, my voice, my color, or my words, that you conceive me to be angry? I cannot think that my eyes betray any ferocity, nor is my countenance disturbed or my voice boisterous; neither do I foam at the mouth, nor are my cheeks red; nor do I say anything indecent or to be repented of; nor do I tremble or seem greatly agitated. These, though you may not know it, are the usual signs of anger." Then, turning to the person who was whipping him: "Whilst this man and I," said he, "are disputing, do you go on with your employment."

Discussion on One of Solon's Laws

In those very ancient laws of Solon which were inscribed at Athens on wooden tables, and which, from veneration to him, the Athenians, to render eternal, had sanctioned with punishments and religious oaths, Aristotle relates there was one to this effect: If in any tumultuous dissension a sedition should ensue, and the people divide themselves into two parties, and from this irritation of their minds both sides should take arms and fight; then he who in this unfortunate period of civil discord should join himself to neither party, but should individually withdraw himself from the common calamity of the city, should be deprived of his house, his family and fortunes, and be driven into exile from his country. When I had read this law of Solon, who was eminent for his wisdom, I was at first impressed with great astonishment, wondering for what reason he should think those men deserving of punishment who withdrew themselves from sedition and a civil war. Then a person who had profoundly and carefully examined the use and purport of this law, affirmed that it was calculated not to increase but terminate sedition; and indeed it really is so, for if all the more respectable, who were at first unable to check sedition, and could not overawe the divided and infatuated people, join themselves to one part or other, it will happen that when they are divided on both sides, and each party begins to be ruled and moderated by them, as men of superior influence, harmony will by their means be sooner restored and confirmed; for whilst they regulate and temper their own parties respectively, they would rather see their opponents conciliated than destroyed. Favorinus the philosopher was of opinion that the same thing ought to be done in the disputes of brothers and of friends: that they who are benevolently inclined to both sides, but have little influence in restoring harmony, from being considered as doubtful friends, should decidedly take one part or other; by which act they will obtain more effectual power in restoring harmony to both. At present, says he, the friends of both think they do well by leaving and deserting both, thus giving them up to malignant or sordid lawyers, who inflame their resentments and disputes from animosity or from avarice.

The Nature of Sight

I have remarked various opinions among philosophers concerning the causes of sight and the nature of vision. The Stoics affirm the causes of sight to be an emission of radii from the eyes against those things which are capable of being seen, with an expansion at the same time of the air. But Epicurus thinks that there proceed from all bodies certain images of the bodies themselves, and that these impress themselves upon the eyes, and that thence arises the sense of sight. Plato is of opinion that a species of fire and light issues from the eyes, and that this, being united and continued either with the light of the sun or the light of some other fire, by its own, added to the external force, enables us to see whatever it meets and illuminates.

But on these things it is not worth while to trifle further; and I recur to an opinion of the Neoptolemus of Ennius, whom I have before mentioned: he thinks that we should taste of philosophy, but not plunge in it over head and ears.

Earliest Libraries

Pisistratus the tyrant is said to have been the first who supplied books of the liberal sciences at Athens for public use. Afterwards the Athenians themselves with great care and pains increased their number; but all this multitude of books, Xerxes, when he obtained possession of Athens and burned the whole of the city except the citadel, seized and carried away to Persia. But King Seleucus, who was called Nicanor, many years afterwards, was careful that all of them should be again carried back to Athens.

A prodigious number of books were in succeeding times collected by the Ptolemies in Egypt, to the amount of near seven hundred thousand volumes. But in the first Alexandrine war the whole library, during the plunder of the city, was destroyed by fire; not by any concerted design, but accidentally by the auxiliary soldiers.

Realistic Acting

There was an actor in Greece of great celebrity, superior to the rest in the grace and harmony of his voice and action. His name, it is said, was Polus, and he acted in the tragedies of the more eminent poets, with great knowledge and accuracy. This Polus lost by death his only and beloved son. When he had sufficiently indulged his natural grief, he returned to his employment. Being at this time to act the 'Electra' of Sophocles at Athens, it was his part to carry an urn as containing the bones of Orestes. The argument of the fable is so imagined that Electra, who is presumed to carry the relics of her brother, laments and commiserates his end, who is believed to have died a violent death. Polus, therefore, clad in the mourning habit of Electra, took from the tomb the bones and urn of his son, and as if embracing Orestes, filled the place, not with the image and imitation, but with the sighs and lamentations of unfeigned sorrow. Therefore, when a fable seemed to be represented, real grief was displayed.

The Athlete's End

Milo of Crotona, a celebrated wrestler, who as is recorded was crowned in the fiftieth Olympiad, met with a lamentable and extraordinary death. When, now an old man, he had desisted from his athletic art and was journeying alone in the woody parts of Italy, he saw an oak very near the roadside, gaping in the middle of the trunk, with its branches extended: willing, I suppose, to try what strength he had left, he put his fingers into the fissure of the tree, and attempted to pluck aside and separate the oak, and did actually tear and divide it in the middle; but when the oak was thus split in two, and he relaxed his hold as having accomplished his intention, upon a cessation of the force it returned to its natural position, and left the man, when it united, with his hands confined, to be torn by wild beasts.

Translation of Rev. W. Beloe.

GESTA ROMANORUM

hat are the 'Gesta Romanorum'? The most curious and interesting of all collections of popular tales. Negatively, one thing they are not: that is, they are not Deeds of the Romans, the acts of the heirs of the Cæsars. All such allusions are the purest fantasy. The great "citee of Rome," and some oddly dubbed emperor thereof, indeed the entire background, are in truth as unhistorical and imaginary as the tale itself.

Such stories are very old. So far back did they spring that it would be idle to conjecture their origin. In the centuries long before Caxton, the centuries before manuscript-writing filled up the leisure hours of the monks, the 'Gesta,' both in the Orient and in the Occident, were brought forth. Plain, direct, and unvarnished, they are the form in which the men of ideas of those rude times approached and entertained, by accounts of human joy and woe, their brother men of action. Every race of historic importance, from the eastern Turanians to the western Celts, has produced such legends. Sometimes they delight the lover of folk-lore; sometimes they belong to the Dryasdust antiquarian. But our 'Gesta,' with their directness and naïveté, with their occasional beauty of diction and fine touches of sympathy and imagination,—even with their Northern lack of grace,—are properly a part of literature. In these 'Deeds' is found the plot or ground-plan of such master works as 'King Lear' and the 'Merchant of Venice,' and the first cast of material refined by Chaucer, Gower, Lydgate, Schiller, and other writers.

Among the people in mediaeval times such tales evidently passed from mouth to mouth. They were the common food of fancy and delight to our forefathers, as they gathered round the fire in stormy weather. Their recital enlivened the women's unnumbered hours of spinning, weaving, and embroidery. As the short days of the year came on, there must have been calls for 'The Knights of Baldak and Lombardy,' 'The Three Caskets,' or 'The White and Black Daughters,' as nowadays we go to our book-shelves for the stories that the race still loves, and ungraciously enjoy the silent telling.

Such folk-stories as those in the 'Gesta' are in the main made of, must have passed from district to district and even from nation to nation, by many channels,—chief among them the constant wanderings of monks and minstrels,—becoming the common heritage of many peoples, and passing from secular to sacerdotal use. The mediæval Church, with the acuteness that characterized it, seized on the pretty tales, and adding to them the moralizing which a crude system of ethics enjoined, carried its spoils to the pulpit. Even the fables of pagan Æsop were thus employed.

In the twelfth century the ecclesiastical forces were appropriating to their use whatever secular rights and possessions came within their grasp. A common ardor permitted and sustained this aggrandizement, and the devotion that founded and swelled the mendicant orders of Francis and Dominic, and led the populace to carry with prayers and psalm-singing the stones of which great cathedrals were built, readily gave their hearth-tales to illustrate texts and inculcate doctrines. A habit of interpreting moral and religious precepts by allegory led to the far-fetched, sometimes droll, and always naive "moralities" which commonly follow each one of the 'Gesta.' The more popular the tale, the more easily it held the attention; and the priests with telling directness brought home the moral to the simple-minded. The innocent joys and sad offenses of humanity interpreted the Church's whole system of theology, and the stories, committed to writing by the priests, were thus preserved.

The secular tales must have been used in the pulpit for some time before their systematic collection was undertaken. The zeal for compiling probably reached its height in the age of Pierre Bercheure, who died in 1362. To Bercheure, prior of the Benedictine Convent of St. Eloi at Paris, the collection of 'Gesta Romanorum' has been ascribed. A German scholar, however, Herr Österley, who published in 1872 the result of an investigation of one hundred and sixty-five manuscripts, asserts that the 'Gesta' were originally compiled towards the end of the thirteenth century in England, from which country they were taken to the Continent, there undergoing various alterations. "The popularity of the original 'Gesta,'" says Sir F. Madden, "not only on the Continent but among the English clergy, appears to have induced some person, apparently in the reign of Richard the Second, to undertake a similar compilation in this country." The 'Anglo-Latin Gesta' is the immediate original of the early English translation from which the following stories are taken, with slight verbal changes.

The word Gesta, in mediæval Latin, means notable or historic act or exploit. The Church, drawing all power, consequence, and grace from Rome, naturally looked back to the Roman empire for historic examples. In this fact we find the reason of the name. The tales betray an entire ignorance of history. In one, for example, a statue is raised to Julius Cæsar twenty-two years after the founding of Rome; while in another, Socrates, Alexander, and the Emperor Claudius are living together in Rome.

It is a pleasant picture which such legends bring before our eyes. The old parish church of England, which with its yards is a common meeting-place for the people's fairs and wakes, and even for their beer-brewing; the simple rustics forming the congregation; the tonsured head of the priest rising above the pulpit,—a monk from the neighboring abbey, who earns his brown bread and ale and venison by endeavors to move the moral sentiments which lie at the root of the Anglo-Saxon character and beneath the apparent stolidity of each yokel. Many of the tales are unfit for reproduction in our more mincing times. The faithlessness of wives—with no reference whatever to the faithlessness of husbands—is a favorite theme with these ancient cenobites.

It is possible, Herr Österley thinks, that the conjecture of Francis Douce may be true, and the 'Gesta' may after all have been compiled in Germany. But the bulk of the evidence goes to prove an English origin. The earliest editions were published at Utrecht and at Cologne. The English translation, from the text of the Latin of the reign of Richard II., was first printed by Wynkyn de Worde between 1510 and 1515. In 1577 Richard Robinson published a revised edition of Wynkyn de Worde's. The work became again popular, and between 1648 and 1703 at least eight issues were sold. An English translation by Charles Swan from the Latin text was first published in 1824, and reissued under the editorship of Thomas Wright in 1872 as a part of Bohn's Library.

THEODOSIUS THE EMPEROURE[A]

Theodosius reigned a wise emperour in the cite of Rome, and mighty he was of power; the which emperoure had three doughters. So it liked to this emperour to knowe which of his doughters loved him best; and then he said to the eldest doughter, "How much lovest thou me?" "Forsoth," quoth she, "more than I do myself." "Therefore," quoth he, "thou shalt be heighly advanced;" and married her to a riche and mighty kyng. Then he came to the second, and said to her, "Doughter, how muche lovest thou me?" "As muche forsoth," she said, "as I do myself." So the emperoure married her to a duke. And then he said to the third doughter, "How much lovest thou me?" "Forsoth," quoth she, "as muche as ye be worthy, and no more." Then said the emperoure, "Doughter, since thou lovest me no more, thou shalt not be married so richely as thy sisters be." And then he married her to an earl.

After this it happened that the emperour held battle against the Kyng of Egipt, and the kyng drove the emperour oute of the empire, in so muche that the emperour had no place to abide inne. So he wrote lettres ensealed with his ryng to his first doughter that said that she loved him more than her self, for to pray her of succoring in that great need, bycause he was put out of his empire. And when the doughter had red these lettres she told it to the kyng her husband. Then quoth the kyng, "It is good that we succor him in his need. I shall," quoth he, "gather an host and help him in all that I can or may; and that will not be done withoute great costage." "Yea," quoth she, "it were sufficiant if that we would graunt him V knyghtes to be fellowship with him while he is oute of his empire." And so it was done indeed; and the doughter wrote again to the fader that other help might he not have, but V knyghtes of the kynges to be in his fellowship, at the coste of the kyng her husband.

And when the emperour heard this he was hevy in his hert and said, "Alas! alas! all my trust was in her; for she said she loved me more than herself, and therefore I advanced her so high."

Then he wrote to the second, that said she loved him as much as her self. And when she had herd his lettres she shewed his erand to her husband, and gave him in counsel that he should find him mete and drink and clothing, honestly as for the state of such a lord, during tyme of his nede; and when this was graunted she wrote lettres agein to hir fadir.

The Emperour was hevy with this answere, and said, "Since my two doughters have thus grieved me, in sooth I shall prove the third."

And so he wrote to the third that she loved him as muche as he was worthy; and prayed her of succor in his nede, and told her the answere of her two sisters. So the third doughter, when she considered the mischief of her fader, she told her husbond in this fourme: "My worshipful lord, do succor me now in this great nede; my fadir is put out of his empire and his heritage." Then spake he, "What were thy will I did thereto?" "That ye gather a great host," quoth she, "and help him to fight against his enemys." "I shall fulfill thy will," said the earl; and gathered a greate hoste and wente with the emperour at his owne costage to the battle, and had the victorye, and set the emperour again in his heritage.

And then said the emperour, "Blessed be the hour I gat my yonest doughter! I loved her lesse than any of the others, and now in my nede she hath succored me, and the others have failed me, and therefore after my deth she shall have mine empire." And so it was done in dede; for after the deth of the emperour the youngest doughter reigned in his sted, and ended peacefully.

Moralite

Dere Frendis, this emperour may be called each worldly man, the which hath three doughters. The first doughter, that saith, "I love my fadir more than my self," is the worlde, whom a man loveth so well that he expendeth all his life about it; but what tyme he shall be in nede of deth, scarcely if the world will for all his love give him five knyghtes, scil. v. boards for a coffin to lay his body inne in the sepulcre. The second doughter, that loveth her fader as muche as her selfe, is thy wife or thy children or thy kin, the whiche will haply find thee in thy nede to the tyme that thou be put in the erthe. And the third doughter, that loveth thee as muche as thou art worthy, is our Lord God, whom we love too little. But if we come to him in tyme of oure nede with a clene hert and mynd, withoute doute we shall have help of him against the Kyng of Egipt, scil. the Devil; and he shall set us in our owne heritage, scil. the kyngdome of heven. Ad quod nos [etc.].

ANCELMUS THE EMPEROUR[B]

Ancelmus reigned emperour in the cite of Rome, and he wedded to wife the Kinges doughter of Jerusalem, the which was a faire woman and long dwelte in his company.

... Happing in a certaine evening as he walked after his supper in a fair green, and thought of all the worlde, and especially that he had no heir, and how that the Kinge of Naples strongly therefore noyed [harmed] him each year; and so whenne it was night he went to bed and took a sleep and dreamed this: He saw the firmament in its most clearnesse, and more clear than it was wont to be, and the moon was more pale; and on a parte of the moon was a faire-colored bird, and beside her stood two beasts, the which nourished the bird with their heat and breath. After this came divers beasts and birds flying, and they sang so sweetly that the emperour was with the song awaked.

Thenne on the morrow the emperoure had great marvel of his sweven [dream], and called to him divinours [soothsayers] and lords of all the empire, and saide to them, "Deere frendes, telleth me what is the interpretation of my sweven, and I shall reward you; and but if ye do, ye shall be dead." And then they saide, "Lord, show to us this dream, and we shall tell thee the interpretation of it." And then the emperour told them as is saide before, from beginning to ending. And then they were glad, and with a great gladnesse spake to him and saide, "Sir, this was a good sweven. For the firmament that thou sawe so clear is the empire, the which henceforth shall be in prosperity; the pale moon is the empresse.... The little bird is the faire son whom the empresse shall bryng forth, when time cometh; the two beasts been riche men and wise men that shall be obedient to thy childe; the other beasts been other folke, that never made homage and nowe shall be subject to thy sone; the birds that sang so sweetly is the empire of Rome, that shall joy of thy child's birth: and sir, this is the interpretacion of your dream."

When the empresse heard this she was glad enough; and soon she bare a faire sone, and thereof was made much joy. And when the King of Naples heard that, he thought to himselfe: "I have longe time holden war against the emperour, and it may not be but that it will be told to his son, when that he cometh to his full age, howe that I have fought all my life against his fader. Yea," thought he, "he is now a child, and it is good that I procure for peace, that I may have rest of him when he is in his best and I in my worste."

So he wrote lettres to the emperour for peace to be had; and the emperour seeing that he did that more for cause of dread than of love, he sent him worde again, and saide that he would make him surety of peace, with condition that he would be in his servitude and yield him homage all his life, each year. Thenne the kyng called his counsel and asked of them what was best to do; and the lordes of his kyngdom saide that it was goode to follow the emperour in his will:—"In the first ye aske of him surety of peace; to that we say thus: Thou hast a doughter and he hath a son; let matrimony be made between them, and so there shall be good sikernesse [sureness]; also it is good to make him homage and yield him rents." Thenne the kyng sent word to the emperour and saide that he would fulfill his will in all points, and give his doughter to his son in wife, if that it were pleasing to him.

This answer liked well the emperour. So lettres were made of this covenaunt; and he made a shippe to be adeyned [prepared], to lead his doughter with a certain of knightes and ladies to the emperour to be married with his sone. And whenne they were in the shippe and hadde far passed from the lande, there rose up a great horrible tempest, and drowned all that were in the ship, except the maid. Thenne the maide set all her hope strongly in God; and at the last the tempest ceased; but then followed strongly a great whale to devoure this maid. And whenne she saw that, she muche dreaded; and when the night come, the maid, dreading that the whale would have swallowed the ship, smote fire at a stone, and had great plenty of fire; and as long as the fire lasted the whale durst come not near, but about cock's crow the mayde, for great vexacion that she had with the tempest, fell asleep, and in her sleep the fire went out; and when it was out the whale came nigh and swallowed both the ship and the mayde. And when the mayde felt that she was in the womb of a whale, she smote and made great fire, and grievously wounded the whale with a little knife, in so much that the whale drew to the land and died; for that is the kind to draw to the land when he shall die.

And in this time there was an earl named Pirius, and he walked in his disport by the sea, and afore him he sawe the whale come toward the land. He gathered great help and strength of men; and with diverse instruments they smote the whale in every part of him. And when the damsell heard the great strokes she cried with an high voice and saide, "Gentle sirs, have pity on me, for I am the doughter of a king, and a mayde have been since I was born." Whenne the earl heard this he marveled greatly, and opened the whale and took oute the damsell. Thenne the maide tolde by order how that she was a kyng's doughter, and how she lost her goods in the sea, and how she should be married to the son of the emperour. And when the earl heard these words he was glad, and helde the maide with him a great while, till tyme that she was well comforted; and then he sent her solemnly to the emperour. And whenne he saw her coming, and heard that she had tribulacions in the sea, he had great compassion for her in his heart, and saide to her, "Goode damsell, thou hast suffered muche anger for the love of my son; nevertheless, if that thou be worthy to have him I shall soon prove."

The emperour had made III. vessells, and the first was of clean [pure] golde and full of precious stones outwarde, and within full of dead bones; and it had a superscription in these words: They that choose me shall find in me that they deserve. The second vessell was all of clean silver, and full of worms: and outwarde it had this superscription: They that choose me shall find in me that nature and kind desireth. And the third vessell was of lead and within was full of precious stones, and without was set this scripture [inscription]: They that choose me shall find in me that God hath disposed. These III. vessells tooke the emperour and showed the maide, saying, "Lo! deer damsell, here are three worthy vessellys, and if thou choose [the] one of these wherein is profit and right to be chosen, then thou shalt have my son to husband; and if thou choose that that is not profitable to thee nor to no other, forsooth, thenne thou shalt not have him."

Whenne the doughter heard this and saw the three vessells, she lifted up her eyes to God and saide:—"Thou, Lord, that knowest all things, graunt me thy grace now in the need of this time, scil. that I may choose at this time, wherethrough [through which] I may joy the son of the emperour and have him to husband." Thenne she beheld the first vessell that was so subtly [cunningly] made, and read the superscription; and thenne she thought, "What have I deserved for to have so precious a vessell? and though it be never so gay without, I know not how foul it is within;" so she tolde the emperour that she would by no way choose that. Thenne she looked to the second, that was of silver, and read the superscription; and thenne she said, "My nature and kind asketh but delectation of the flesh, forsooth, sir," quoth she; "and I refuse this." Thenne she looked to the third, that was of lead, and read the superscription, and then she, saide, "In sooth, God disposed never evil; forsooth, that which God hath disposed will I take and choose."

And when the emperour sawe that he saide, "Goode damesell, open now that vessell and see what thou hast found." And when it was opened it was full of gold and precious stones. And thenne the emperour saide to her again, "Damesell, thou hast wisely chosen and won my son to thine husband." So the day was set of their bridal, and great joy was made; and the son reigned after the decease of the fadir, the which made faire ende. Ad quod nos perducat! Amen.

Moralite

Deere frendis, this emperour is the Father of Heaven, the whiche made man ere he tooke flesh. The empress that conceived was the blessed Virgin, that conceived by the annunciation of the angel. The firmament was set in his most clearnesse, scil. the world was lighted in all its parts by the concepcion of the empress Our Lady.... The little bird that passed from the side of the moon is our Lord Jesus Christ, that was born at midnight and lapped [wrapped] in clothes and set in the crib. The two beasts are the oxen and the asses. The beasts that come from far parts are the herds [shepherds] to whom the angels saide, Ecce annuncio vobis gaudium magnum,—"Lo! I shew you a great joy." The birds that sang so sweetly are angels of heaven, that sang Gloria in excelsis Deo. The king that held such war is mankind, that was contrary to God while that it was in power of the Devil; but when our Lord Jesus Christ was born, then mankind inclined to God, and sent for peace to be had, when he took baptism and saide that he gave him to God and forsook the Devil. Now the king gave his doughter to the son of the emperour, scil. each one of us ought to give to God our soul in matrimony; for he is ready to receive her to his spouse [etc.].

HOW AN ANCHORESS WAS TEMPTED BY THE DEVIL

There was a woman some time in the world living that sawe the wretchedness, the sins, and the unstableness that was in the worlde; therefore she left all the worlde, and wente into the deserte, and lived there many years with roots and grasse, and such fruit as she might gete; and dranke water of the welle-spryng, for othere livelihood had she none. Atte laste, when she had longe dwelled there in that place, the Devil in likenesse of a woman, come to this holy woman's place; and when he come there he knocked at the door. The holy woman come to the door and asked what she would? She saide, "I pray thee, dame, that thou wilt harbor me this night; for this day is at an end, and I am afeard that wild beasts should devour me." The good woman saide, "For God's love ye are welcome to me; and take such as God sendeth." They sat them down together, and the good woman sat and read saints' lives and other good things, till she come to this writing, "Every tree that bringeth not forth good fruit shall be caste downe, and burnt in helle." "That is sooth," saide the Fiend, "and therefore I am adread; for if we lead oure life alone, therefore we shall have little meed, for when we dwelle alone we profit none but oure self. Therefore it were better, me thinketh, to go and dwelle among folke, for to give example to man and woman dwelling in this worlde. Then shall we have much meed." When this was saide they went to reste. This good woman thought faste in her heart that she might not sleep nor have no rest, for the thing that the Fiend had said. Anon this woman arose and saide to the other woman, "This night might I have no reste for the words that thou saide yester even. Therefore I wot never what is best to be done for us." Then the Devil said to her again, "It is best to go forth to profit to othere that shall be glad of oure coming, for that is much more worth than to live alone." Then saide the woman to the Fiend, "Go we now forthe on oure way, for me thinketh it is not evil to essay." And when she should go oute at the door, she stood still, and said thus, "Now, sweet Lady, Mother of mercy, and help at all need, now counsell me the beste, and keep me both body and soule from deadly sin." When she had said these words with good heart and with good will, oure Lady come and laide her hande on her breast, and put her in again, and bade her that she should abide there, and not be led by falsehood of oure Enemy. The Fiend anon went away that she saw him no more there. Then she was full fain that she was kept and not beguiled of her enemy. Then she said on this wise to oure Blessed Lady that is full of mercy and goodnesse, "I thanke thee nowe with all my heart, specially for this keeping and many more that thou hast done to me oft since; and good Lady, keep me from henceforward." Lo! here may men and women see how ready this good Lady is to help her servants at all their need, when they call to her for help, that they fall not in sin bestirring of the wicked enemy the false Fiend.

EDWARD GIBBON.

EDWARD GIBBON

(1737-1794)

BY W. E. H. LECKY

he history of Gibbon has been described by John Stuart Mill as the only eighteenth-century history that has withstood nineteenth-century criticism; and whatever objections modern critics may bring against some of its parts, the substantial justice of this verdict will scarcely be contested. No other history of that century has been so often reprinted, annotated, and discussed, or remains to the present day a capital authority on the great period of which it treats. As a composition it stands unchallenged and conspicuous among the masterpieces of English literature, while as a history it covers a space of more than twelve hundred years, including some of the most momentous events in the annals of mankind.

Gibbon was born at Putney, Surrey, April 27th, 1737. Though his father was a member of Parliament and the owner of a moderate competence, the author of this great work was essentially a self-educated man. Weak health and almost constant illness in early boyhood broke up his school life,—which appears to have been fitfully and most imperfectly conducted,—withdrew him from boyish games, but also gave him, as it has given to many other shy and sedentary boys, an early and inveterate passion for reading. His reading, however, was very unlike that of an ordinary boy. He has given a graphic picture of the ardor with which, when he was only fourteen, he flung himself into serious but unguided study; which was at first purely desultory, but gradually contracted into historic lines, and soon concentrated itself mainly on that Oriental history which he was one day so brilliantly to illuminate. "Before I was sixteen," he says, "I had exhausted all that could be learned in English of the Arabs and Persians, the Tartars and Turks; and the same ardor led me to guess at the French of D'Herbelot, and to construe the barbarous Latin of Pocock's 'Abulfaragius.'"

His health however gradually improved, and when he entered Magdalen College, Oxford, it might have been expected that a new period of intellectual development would have begun; but Oxford had at this time sunk to the lowest depth of stagnation, and to Gibbon it proved extremely uncongenial. He complained that he found no guidance, no stimulus, and no discipline, and that the fourteen months he spent there were the most idle and unprofitable of his life. They were very unexpectedly cut short by his conversion to the Roman Catholic faith, which he formally adopted at the age of sixteen.

This conversion is, on the whole, the most surprising incident of his calm and uneventful life. The tendencies of the time, both in England and on the Continent, were in a wholly different direction. The more spiritual and emotional natures were now passing into the religious revival of Wesley and Whitefield, which was slowly transforming the character of the Anglican Church and laying the foundations of the great Evangelical party. In other quarters the predominant tendencies were towards unbelief, skepticism, or indifference. Nature seldom formed a more skeptical intellect than that of Gibbon, and he was utterly without the spiritual insight, or spiritual cravings, or overmastering enthusiasms, that produce and explain most religious changes. Nor was he in the least drawn towards Catholicism on its aesthetic side. He had never come in contact with its worship or its professors; and to his unimaginative, unimpassioned, and profoundly intellectual temperament, no ideal type could be more uncongenial than that of the saint. He had however from early youth been keenly interested in theological controversies. He argued, like Lardner and Paley, that miracles are the Divine attestation of orthodoxy. Middleton convinced him that unless the Patristic writers were wholly undeserving of credit, the gift of miracles continued in the Church during the fourth and fifth centuries; and he was unable to resist the conclusion that during that period many of the leading doctrines of Catholicism had passed into the Church. The writings of the Jesuit Parsons, and still more the writings of Bossuet, completed the work which Middleton had begun. Having arrived at this conclusion, Gibbon acted on it with characteristic honesty, and was received into the Church on the 8th of June, 1753.

The English universities were at this time purely Anglican bodies, and the conversion of Gibbon excluded him from Oxford. His father judiciously sent him to Lausanne to study with a Swiss pastor named Pavilliard, with whom he spent five happy and profitable years. The theological episode was soon terminated. Partly under the influence of his teacher, but much more through his own reading and reflections, he soon disentangled the purely intellectual ties that bound him to the Church of Rome; and on Christmas Day, 1754, he received the sacrament in the Protestant church of Lausanne.

His residence at Lausanne was very useful to him. He had access to books in abundance, and his tutor, who was a man of great good sense and amiability but of no remarkable capacity, very judiciously left his industrious pupil to pursue his studies in his own way. "Hiving wisdom with each studious year," as Byron so truly says, he speedily amassed a store of learning which has seldom been equaled. His insatiable love of knowledge, his rare capacity for concentrated, accurate, and fruitful study, guided by a singularly sure and masculine judgment, soon made him, in the true sense of the word, one of the best scholars of his time. His learning, however, was not altogether of the kind that may be found in a great university professor. Though the classical languages became familiar to him, he never acquired or greatly valued the minute and finished scholarship which is the boast of the chief English schools; and careful students have observed that in following Greek books he must have very largely used the Latin translations. Perhaps in his capacity of historian this deficiency was rather an advantage than the reverse. It saved him from the exaggerated value of classical form, and from the neglect of the more corrupt literatures, to which English scholars have been often prone. Gibbon always valued books mainly for what they contained, and he had early learned the lesson which all good historians should learn: that some of his most valuable materials will be found in literatures that have no artistic merit; in writers who, without theory and almost without criticism, simply relate the facts which they have seen, and express in unsophisticated language the beliefs and impressions of their time.

Lausanne and not Oxford was the real birthplace of his intellect, and he returned from it almost a foreigner. French had become as familiar to him as his own tongue; and his first book, a somewhat superficial essay on the study of literature, was published in the French language. The noble contemporary French literature filled him with delight, and he found on the borders of the Lake of Geneva a highly cultivated society to which he was soon introduced, and which probably gave him more real pleasure than any in which he afterwards moved. With Voltaire himself he had some slight acquaintance, and he at one time looked on him with profound admiration; though fuller knowledge made him sensible of the flaws in that splendid intellect. I am here concerned with the life of Gibbon only in as far as it discloses the influences that contributed to his master work, and among these influences the foreign element holds a prominent place. There was little in Gibbon that was distinctively English; his mind was essentially cosmopolitan. His tastes, ideals, and modes of thought and feeling turned instinctively to the Continent.

In one respect this foreign type was of great advantage to his work. Gibbon excels all other English historians in symmetry, proportion, perspective, and arrangement, which are also the pre-eminent and characteristic merits of the best French literature. We find in his writing nothing of the great miscalculations of space that were made by such writers as Macaulay and Buckle; nothing of the awkward repetitions, the confused arrangement, the semi-detached and disjointed episodes that mar the beauty of many other histories of no small merit. Vast and multifarious as are the subjects which he has treated, his work is a great whole, admirably woven in all its parts. On the other hand, his foreign taste may perhaps be seen in his neglect of the Saxon element, which is the most vigorous and homely element in English prose. Probably in no other English writer does the Latin element so entirely predominate. Gibbon never wrote an unmeaning and very seldom an obscure sentence; he could always paint with sustained and stately eloquence an illustrious character or a splendid scene: but he was wholly wanting in the grace of simplicity, and a monotony of glitter and of mannerism is the great defect of his style. He possessed, to a degree which even Tacitus and Bacon had hardly surpassed, the supreme literary gift of condensation, and it gives an admirable force and vividness to his narrative; but it is sometimes carried to excess. Not unfrequently it is attained by an excessive allusiveness, and a wide knowledge of the subject is needed to enable the reader to perceive the full import and meaning conveyed or hinted at by a mere turn of phrase. But though his style is artificial and pedantic, and greatly wanting in flexibility, it has a rare power of clinging to the memory, and it has profoundly influenced English prose. That excellent judge Cardinal Newman has said of Gibbon, "I seem to trace his vigorous condensation and peculiar rhythm at every turn in the literature of the present day."

It is not necessary to relate here in any detail the later events of the life of Gibbon. There was his enlistment as captain in the Hampshire militia. It involved two and a half years of active service, extending from May 1760 to December 1762; and as Gibbon afterwards acknowledged, if it interrupted his studies and brought him into very uncongenial duties and societies, it at least greatly enlarged his acquaintance with English life, and also gave him a knowledge of the rudiments of military science, which was not without its use to the historian of so many battles. There was a long journey, lasting for two years and five months, in France and Italy, which greatly confirmed his foreign tendencies. In Paris he moved familiarly in some of the best French literary society; and in Rome, as he tells us in a well-known passage, while he sat "musing amidst the ruins of the Capitol while the barefooted friars were singing vespers in the Temple of Jupiter" (which is now the Church of the Ara Cœli),—on October 15th, 1764,—he first conceived the idea of writing the history of the decline and fall of Rome.

There was also that very curious episode in his life, lasting from 1774 to 1782,—his appearance in the House of Commons. He had declined an offer of his father's to purchase a seat for him in 1760; and fourteen years later, when his father was dead, when his own circumstances were considerably contracted, he received and accepted at the hands of a family connection the offer of a seat. His Parliamentary career was entirely undistinguished, and he never even opened his mouth in debate,—a fact which was not forgotten when very recently another historian was candidate for a seat in Parliament. In truth, this somewhat shy and reserved scholar, with his fastidious taste, his eminently judicial mind, and his highly condensed and elaborate style, was singularly unfit for the rough work of Parliamentary discussion. No one can read his books without perceiving that his English was not that of a debater; and he has candidly admitted that he entered Parliament without public spirit or serious interest in politics, and that he valued it chiefly as leading to an office which might restore the fortune which the extravagance of his father had greatly impaired. His only real public service was the composition in French of a reply to the French manifesto which was issued at the beginning of the war of 1778. He voted steadily and placidly as a Tory, and it is not probable that in doing so he did any violence to his opinions. Like Hume, he shrank with an instinctive dislike from all popular agitations, from all turbulence, passion, exaggeration, and enthusiasm; and a temperate and well-ordered despotism was evidently his ideal. He showed it in the well-known passage in which he extols the benevolent despotism of the Antonines as without exception the happiest period in the history of mankind, and in the unmixed horror with which he looked upon the French Revolution that broke up the old landmarks of Europe, For three years he held an office in the Board of Trade, which added considerably to his income without adding greatly to his labors, and he supported steadily the American policy of Lord North and the Coalition ministry of North and Fox; but the loss of his office and the retirement of North soon drove him from Parliament, and he shortly after took up his residence at Lausanne.

But before this time a considerable part of his great work had been accomplished. The first quarto volume of the 'Decline and Fall' appeared in February 1776. As is usually the case with historical works, it occupied a much longer period than its successors, and was the fruit of about ten years of labor. It passed rapidly through three editions, received the enthusiastic eulogy of Hume and Robertson, and was no doubt greatly assisted in its circulation by the storm of controversy that arose about his Fifteenth and Sixteenth Chapters. In April 1781 two more volumes appeared, and the three concluding volumes were published together on the 8th of May, 1788, being the fifty-first birthday of the author.

A work of such magnitude, dealing with so vast a variety of subjects, was certain to exhibit some flaws. The controversy at first turned mainly upon its religious tendency. The complete skepticism of the author, his aversion to the ecclesiastical type which dominated in the period of which he wrote, and his unalterable conviction that Christianity, by diverting the strength and enthusiasm of the Empire from civic into ascetic and ecclesiastical channels, was a main cause of the downfall of the Empire and of the triumph of barbarism, gave him a bias which it was impossible to overlook. On no other subject is his irony more bitter or his contempt so manifestly displayed. Few good critics will deny that the growth of the ascetic spirit had a large part in corroding and enfeebling the civic virtues of the Empire; but the part which it played was that of intensifying a disease that had already begun, and Gibbon, while exaggerating the amount of the evil, has very imperfectly described the great services rendered even by a monastic Church in laying the basis of another civilization and in mitigating the calamities of the barbarian invasion. The causes he has given of the spread of Christianity in the Fifteenth Chapter were for the most part true causes, but there were others of which he was wholly insensible. The strong moral enthusiasms that transform the character and inspire or accelerate all great religious changes lay wholly beyond the sphere of his realizations. His language about the Christian martyrs is the most repulsive portion of his work; and his comparison of the sufferings caused by pagan and Christian persecutions is greatly vitiated by the fact that he only takes account of the number of deaths, and lays no stress on the profuse employment of atrocious tortures, which was one of the most distinct features of the pagan persecutions. At the same time, though Gibbon displays in this field a manifest and a distorting bias, he never, like some of his French contemporaries, sinks into the mere partisan, awarding to one side unqualified eulogy and to the other unqualified contempt. Let the reader who doubts this examine and compare his masterly portraits of Julian and of Athanasius, and he will perceive how clearly the great historian could recognize weaknesses in the characters by which he was most attracted, and elements of true greatness in those by which he was most repelled. A modern writer, in treating of the history of religions, would have given a larger space to comparative religion, and to the gradual, unconscious, and spontaneous growth of myths in the twilight periods of the human mind. These however were subjects which were scarcely known in the days of Gibbon, and he cannot be blamed for not having discussed them.

Another class of objections which has been brought against him is that he is weak upon the philosophical side, and deals with history mainly as a mere chronicle of events, and not as a chain of causes and consequences, a series of problems to be solved, a gradual evolution which it is the task of the historian to explain. Coleridge, who detested Gibbon and spoke of him with gross injustice, has put this objection in the strongest form. He accuses him of having reduced history to a mere collection of splendid anecdotes; of noting nothing but what may produce an effect; of skipping from eminence to eminence without ever taking his readers through the valleys between; of having never made a single philosophical attempt to fathom the ultimate causes of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, which is the very subject of his history. That such charges are grossly exaggerated will be apparent to any one who will carefully read the Second and Third Chapters, describing the state and tendencies of the Empire under the Antonines; or the chapters devoted to the rise and character of the barbarians, to the spread of Christianity, to the influence of monasticism, to the jurisprudence of the republic and of the Empire; nor would it be difficult to collect many acute and profound philosophical remarks from other portions of the history. Still, it may be admitted that the philosophical side is not its strongest part. Social and economical changes are sometimes inadequately examined and explained, and we often desire fuller information about the manners and life of the masses of the people. As far as concerns the age of the Antonines, this want has been amply supplied by the great work of Friedländer.

History, like many other things in our generation, has fallen largely into the hands of specialists; and it is inevitable that men who have devoted their lives to a minute examination of short periods should be able to detect some deficiencies and errors in a writer who traversed a period of more than twelve hundred years. Many generations of scholars have arisen since Gibbon; many new sources of knowledge have become available, and archæology especially has thrown a flood of new light on some of the subjects he treated. Though his knowledge and his narrative are on the whole admirably sustained, there are periods which he knew less well and treated less fully than others. His account of the Crusades is generally acknowledged to be one of the most conspicuous of these, and within the last few years there has arisen a school of historians who protest against the low opinion of the Byzantine Empire which was held by Gibbon, and was almost universal among scholars till the present generation. That these writers have brought into relief certain merits of the Lower Empire which Gibbon had neglected, will not be denied; but it is perhaps too early to decide whether the reaction has not, like most reactions, been carried to extravagance, and whether in its general features the estimate of Gibbon is not nearer the truth than some of those which are now put forward to replace it.

Much must no doubt be added to the work of Gibbon in order to bring it up to the level of our present knowledge; but there is no sign that any single work is likely to supersede it or to render it useless to the student; nor does its survival depend only or even mainly on its great literary qualities, which have made it one of the classics of the language. In some of these qualities Hume was the equal of Gibbon and in others his superior, and he brought to his history a more penetrating and philosophical intellect and an equally calm and unenthusiastic nature; but the study which Hume bestowed on his subject was so superficial and his statements were often so inaccurate, that his work is now never quoted as an authority. With Gibbon it is quite otherwise. His marvelous industry, his almost unrivaled accuracy of detail, his sincere love of truth, his rare discrimination and insight in weighing testimony and in judging character, have given him a secure place among the greatest historians of the world.

His life lasted only fifty-six years; he died in London on January 15th, 1794. With a single exception his history is his only work of real importance. That exception is his admirable autobiography. Gibbon left behind him six distinct sketches, which his friend Lord Sheffield put together with singular skill. It is one of the best specimens of self-portraiture in the language, reflecting with pellucid clearness both the life and character, the merits and defects, of its author. He was certainly neither a hero nor a saint; nor did he possess the moral and intellectual qualities that dominate in the great conflicts of life, sway the passions of men, appeal powerfully to the imagination, or dazzle and impress in social intercourse. He was a little slow, a little pompous, a little affected and pedantic. In the general type of his mind and character he bore much more resemblance to Hume, Adam Smith, or Reynolds, than to Johnson or Burke. A reserved scholar, who was rather proud of being a man of the world; a confirmed bachelor, much wedded to his comforts though caring nothing for luxury, he was eminently moderate in his ambitions, and there was not a trace of passion or enthusiasm in his nature. Such a man was not likely to inspire any strong devotion. But his temper was most kindly, equable, and contented; he was a steady friend, and he appears to have been always liked and honored in the cultivated and uncontentious society in which he delighted. His life was not a great one, but it was in all essentials blameless and happy. He found the work which was most congenial to him. He pursued it with admirable industry and with brilliant success, and he left behind him a book which is not likely to be forgotten while the English language endures.

[A] The story of King Lear and his three daughters.

[B] The story of the three caskets in 'The Merchant of Venice.'

ZENOBIA

Aurelian had no sooner secured the person and provinces of Tetricus, than he turned his arms against Zenobia, the celebrated queen of Palmyra and the East. Modern Europe has produced several illustrious women who have sustained with glory the weight of empire; nor is our own age destitute of such distinguished characters. But if we except the doubtful achievements of Semiramis, Zenobia is perhaps the only female whose superior genius broke through the servile indolence imposed on her sex by the climate and manners of Asia. She claimed her descent from the Macedonian kings of Egypt, equaled in beauty her ancestor Cleopatra, and far surpassed that princess in chastity and valor. Zenobia was esteemed the most lovely as well as the most heroic of her sex. She was of a dark complexion (for in speaking of a lady these trifles become important). Her teeth were of a pearly whiteness, and her large black eyes sparkled with uncommon fire, tempered by the most attractive sweetness. Her voice was strong and harmonious. Her manly understanding was strengthened and adorned by study. She was not ignorant of the Latin tongue, but possessed in equal perfection the Greek, the Syriac, and the Egyptian languages. She had drawn up for her own use an epitome of Oriental history, and familiarly compared the beauties of Homer and Plato under the tuition of the sublime Longinus.

This accomplished woman gave her hand to Odenathus, who, from a private station, raised himself to the dominion of the East. She soon became the friend and companion of a hero. In the intervals of war, Odenathus passionately delighted in the exercise of hunting; he pursued with ardor the wild beasts of the desert,—lions, panthers, and bears; and the ardor of Zenobia in that dangerous amusement was not inferior to his own. She had inured her constitution to fatigue, disdained the use of a covered carriage, generally appeared on horseback in a military habit, and sometimes marched several miles on foot at the head of the troops. The success of Odenathus was in a great measure ascribed to her incomparable prudence and fortitude. Their splendid victories over the Great King, whom they twice pursued as far as the gates of Ctesiphon, laid the foundations of their united fame and power. The armies which they commanded, and the provinces which they had saved, acknowledged not any other sovereigns than their invincible chiefs. The Senate and people of Rome revered a stranger who had avenged their captive emperor, and even the insensible son of Valerian accepted Odenathus for his legitimate colleague.

After a successful expedition against the Gothic plunderers of Asia, the Palmyrenian prince returned to the city of Emesa in Syria. Invincible in war, he was there cut off by domestic treason; and his favorite amusement of hunting was the cause, or at least the occasion, of his death. His nephew Mæonius presumed to dart his javelin before that of his uncle; and though admonished of his error, repeated the same insolence. As a monarch and as a sportsman, Odenathus was provoked, took away his horse, a mark of ignominy among the barbarians, and chastised the rash youth by a short confinement. The offense was soon forgot, but the punishment was remembered; and Mæonius, with a few daring associates, assassinated his uncle in the midst of a great entertainment. Herod, the son of Odenathus, though not of Zenobia, a young man of a soft and effeminate temper, was killed with his father. But Mæonius obtained only the pleasure of revenge by this bloody deed. He had scarcely time to assume the title of Augustus, before he was sacrificed by Zenobia to the memory of her husband.

With the assistance of his most faithful friends, she immediately filled the vacant throne, and governed with manly counsels Palmyra, Syria, and the East, above five years. By the death of Odenathus, that authority was at an end which the Senate had granted him only as a personal distinction; but his martial widow, disdaining both the Senate and Gallienus, obliged one of the Roman generals who was sent against her to retreat into Europe, with the loss of his army and his reputation. Instead of the little passions which so frequently perplex a female reign, the steady administration of Zenobia was guided by the most judicious maxims of policy. If it was expedient to pardon, she could calm her resentment; if it was necessary to punish, she could impose silence on the voice of pity. Her strict economy was accused of avarice; yet on every proper occasion she appeared magnificent and liberal. The neighboring States of Arabia, Armenia, and Persia dreaded her enmity and solicited her alliance. To the dominions of Odenathus, which extended from the Euphrates to the frontiers of Bithynia, his widow added the inheritance of her ancestors, the populous and fertile kingdom of Egypt. The Emperor Claudius acknowledged her merit, and was content that while he pursued the Gothic war, she should assert the dignity of the Empire in the East. The conduct however of Zenobia was attended with some ambiguity, nor is it unlikely that she had conceived the design of erecting an independent and hostile monarchy. She blended with the popular manners of Roman princes the stately pomp of the courts of Asia, and exacted from her subjects the same adoration that was paid to the successors of Cyrus. She bestowed on her three sons a Latin education, and often showed them to the troops adorned with the imperial purple. For herself she reserved the diadem, with the splendid but doubtful title of Queen of the East.

When Aurelian passed over into Asia against an adversary whose sex alone could render her an object of contempt, his presence restored obedience to the province of Bithynia, already shaken by the arms and intrigues of Zenobia. Advancing at the head of his legions, he accepted the submission of Ancyra, and was admitted into Tyana, after an obstinate siege, by the help of a perfidious citizen. The generous though fierce temper of Aurelian abandoned the traitor to the rage of the soldiers: a superstitious reverence induced him to treat with lenity the countrymen of Apollonius the philosopher. Antioch was deserted on his approach, till the Emperor, by his salutary edicts, recalled the fugitives, and granted a general pardon to all who from necessity rather than choice had been engaged in the service of the Palmyrenian Queen. The unexpected mildness of such a conduct reconciled the minds of the Syrians, and as far as the gates of Emesa the wishes of the people seconded the terror of his arms.