автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Library of the World's Best Literature, Ancient and Modern, Vol. VIII

LIBRARY OF THE

WORLD'S BEST LITERATURE

ANCIENT AND MODERN

CHARLES DUDLEY WARNER

EDITOR

HAMILTON WRIGHT MABIE

LUCIA GILBERT RUNKLE

GEORGE HENRY WARNER

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Connoisseur Edition

Vol. VIII.

NEW YORK

THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY

Connoisseur Edition

LIMITED TO FIVE HUNDRED COPIES IN HALF RUSSIA

No. ..........

Copyright, 1896, by

R. S. PEALE AND J. A. HILL

All rights reserved

THE ADVISORY COUNCIL

CRAWFORD H. TOY, A. M., LL. D.,

Professor of Hebrew, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

THOMAS R. LOUNSBURY, LL. D., L. H. D.,

Professor of English in the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

WILLIAM M. SLOANE, Ph. D., L. H. D.,

Professor of History and Political Science, Princeton University, Princeton, N. J.

BRANDER MATTHEWS, A. M., LL. B.,

Professor of Literature, Columbia University, New York City.

JAMES B. ANGELL, LL. D.,

President of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.

WILLARD FISKE, A. M., Ph. D.,

Late Professor of the Germanic and Scandinavian Languages and Literatures, Cornell University, Ithaca, N. Y.

EDWARD S. HOLDEN, A. M., LL. D.,

Director of the Lick Observatory, and Astronomer, University of California, Berkeley, Cal.

ALCÉE FORTIER, LIT. D.,

Professor of the Romance Languages, Tulane University, New Orleans, La.

WILLIAM P. TRENT, M. A.,

Dean of the Department of Arts and Sciences, and Professor of English and History, University of the South, Sewanee, Tenn.

PAUL SHOREY, Ph. D.,

Professor of Greek and Latin Literature, University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill.

WILLIAM T. HARRIS, LL. D.,

United States Commissioner of Education, Bureau of Education, Washington, D. C.

MAURICE FRANCIS EGAN, A. M., LL. D.,

Professor of Literature in the Catholic University of America, Washington, D. C.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

VOL. VIII

LIVED PAGE John Calvin1509-1564

3117BY ARTHUR CUSHMAN M

cGIFFERT

Prefatory Address to the 'Institutes' Election and Predestination ('Institutes of the Christian Religion') Freedom of the Will (same) Luiz Vaz de Camoens1524?-1580

3129BY HENRY R. LANG

From 'The Lusiads' The Canzon of Life Adieu to Coimbra Thomas Campbell1777-1844

3159 Hope ('The Pleasures of Hope') The Fall of Poland (same) The Slave (same) Death and a Future Life (same) Lochiel's Warning The Soldier's Dream Lord Ullin's Daughter The Exile of Erin Ye Mariners of England Hohenlinden The Battle of Copenhagen From the 'Ode to Winter' Campion-1619

3184BY ERNEST RHYS

A Hymn in Praise of Neptune Of Corinna's Singing From 'Divine and Moral Songs' To a Coquette Songs from 'Light Conceits of Lovers' George Canning1770-1827

3189 Rogero's Soliloquy ('The Rovers') The Friend of Humanity and the Knife-Grinder On the English Constitution ('Speech on Parliamentary Reform') On Brougham and South America Cesare Cantù1807-1895

3199 The Execution ('Margherita Pusterla') Giosue Carducci1835-

3206BY FRANK SEWALL

Roma ('Poesie') Homer ('Levia Gravia') In a Gothic Church ('Poesie') On the Sixth Centenary of Dante ('Levia Gravia') The Ox ('Poesie') Dante ('Levia Gravia') To Satan ('Poesie') To Aurora ('Odi Barbare') Ruit Hora The Mother Thomas Carew1589?-1639

3221 A Song The Protestation Song The Spring The Inquiry Emilia Flygare-Carlén1807-1892

3225 The Pursuit of the Smugglers ('Merchant House among the Islands') Thomas Carlyle1795-1881

3231BY LESLIE STEPHEN

Labor ('Past and Present') The World in Clothes ('Sartor Resartus') Dante ('Heroes and Hero-Worship') Cromwell (same) The Procession ('French Revolution') The Siege of the Bastille (same) Charlotte Corday (same) The Scapegoat (same) Bliss Carman1861-

3302BY CHARLES G.D. ROBERTS

Hack and Hew At the Granite Gate A Sea Child Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson)1833-

3307 Alice, the Pig-Baby, and the Cheshire Cat ('Alice in Wonderland') The Mock Turtle's Education (same) A Clear Statement (same) The Walrus and the Carpenter ('Through the Looking-Glass') The Baker's Tale ('Hunting of the Snark') You are Old, Father William ('Alice in Wonderland') Casanova (De Seingalt)1725-1803

3321 Casanova's Escape from the Ducal Palace ('Escapes of Casanova and Latude from Prison') Bartolomeo de las Casas1474-1566

3333 Of the Island of Cuba ('A Relation of the First Voyage') Baldassare Castiglione1478-1529

3339 Of the Court of Urbino ('Il Cortegiano') Cato the Censor234-149 B.C.

3347 On Agriculture ('De Agricultura') From the 'Attic Nights' of Aulus Gellius Jacob Cats1577-1660

3353 Fear after the Trouble "A Rich Man Loses his Child, a Poor Man Loses his Cow" Catullus84-54 B.C.?

3359BY J. W. MACKAIL

Dedication for a Volume of Lyrics A Morning Call Home to Sirmio Heart-Break To Calvus in Bereavement The Pinnace An Invitation to Dinner A Brother's Grave Farewell to His Fellow Officers Verses from an Epithalamium Love is All Elegy on Lesbia's Sparrow "Fickle and Changeable Ever" Two Chords Last Word to Lesbia Benvenuto Cellini1500-1571

3371 The Escape from Prison The Casting of Perseus A Necklace of Pearls Benvenuto Loses his Brother An Adventure in Necromancy Benvenuto Loses Self-Control under Severe Provocation (All the above are from Cellini's 'Memoirs,' Symonds's Translation) Celtic Literature 3403BY WILLIAM SHARP AND ERNEST RHYS

I—Irish The Miller of Hell Signs of Home Oisin in Tirnanoge From 'The Coming of Cuculain' The Mystery of Amergin The Song of Fionn Vision of a Fair Woman From 'The Wanderings of Oisin' The Madness of King Goll II—Scottish St. Bridget's Milking Song Prologue to Gaul Columcille Fecit In Hebrid Seas III—Welsh IV—Cornish From 'The Poem of the Passion' From 'Origo Mundi,' in the 'Ordinalia' Cervantes1547-1616

3451BY GEORGE SANTAYANA

Treating of the Character and Pursuits of Don Quixote Of What Happened to Don Quixote when he Left the Inn Don Quixote and Sancho Panza Sally Forth: and the Adventure with the Windmills Sancho Panza and his Wife Teresa Converse Shrewdly Of Sancho Panza's Delectable Discourse with the Duchess Sancho as Governor The Ending of All Don Quixote's AdventuresFULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

VOLUME VIII

PAGEMiniature Painting of the Middle Ages (Colored Plate)

Frontispiece

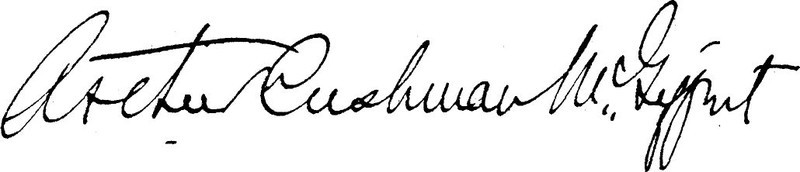

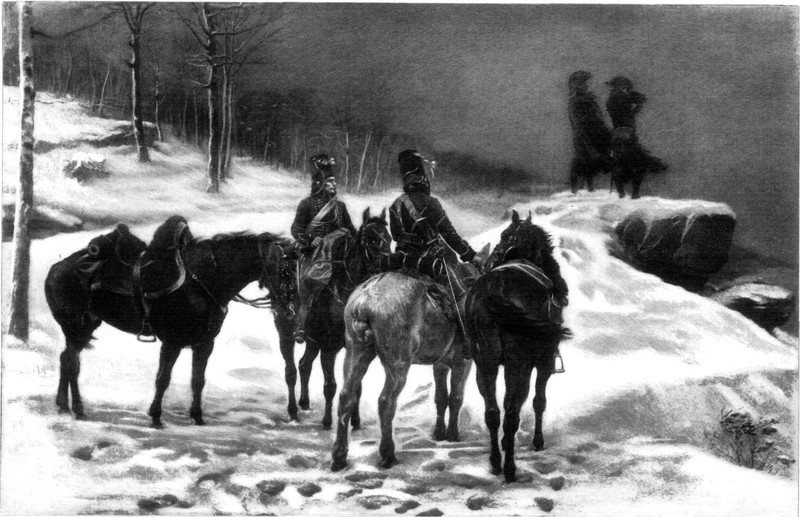

John Calvin (Portrait) 3118 The Septuagint (Fac-simile) 3124 Luiz Vaz de Camoens (Portrait) 3130 "Hohenlinden" (Photogravure) 3178 "Homer" (Photogravure) 3209 Thomas Carlyle (Portrait) 3232 "Charlotte Corday in Prison" (Photogravure) 3290 Benvenuto Cellini (Portrait) 3374 Cervantes (Portrait) 3464VIGNETTE PORTRAITS

Thomas Campbell Bartolorneo de las Casas George Canning Baldassare Castiglione Emilia Flygare-Carlén Jacob Cats Bliss Carman Valerius CatullusJOHN CALVIN

(1509-1564)

BY ARTHUR CUSHMAN McGIFFERT

Though he had apparently renounced forever all thoughts of a clerical life, he retained, even while he was engaged in the study of law and in the more congenial pursuit of literature, his early love for theology; and in 1532, under the influence of some of Luther's writings which happened to fall into his hands, he was converted to the Protestant faith and threw in his fortunes with the little evangelical party in Paris. His intellectual attainments made him a marked man wherever he went, and he speedily became the leading spirit in the circle to which he had attached himself. Compelled soon afterward by the persecuting measures of King Francis I. to flee the country, he took up his residence at Basle and settled down, as he hoped, to a quiet literary life. It was during his stay here that he published in 1536 the first edition of his greatest work, 'The Christian Institutes,' in which is contained the system of theology which has for centuries borne his name, and by which he is best known to the world at large. Probably no other work written by so young a man has ever produced such a wide-spread, profound, and lasting influence. In its original form, it is true, the work was only a brief and simple introduction to the study of the Scriptures, much less imposing and forbidding than the elaborate body of divinity which is now known to theologians as 'Calvin's Institutes': but all the substance of the last edition is to be found in the first; the theology of the one is the theology of the other—the Calvin of 1559 is the Calvin of 1536. The fact that at the age of twenty-six Calvin could publish a system of theology at once so original and so profound—a system, moreover, which with all his activity of intellect and love of truth he never had occasion to modify in any essential particular—is one of the most striking phenomena in the history of the human mind; and yet it is but one of many illustrations of the man's marvelous clearness and comprehensiveness of vision, and of his force and decision of character. His life from beginning to end was the consistent unfolding of a single dominant principle—the unwavering pursuit of a single controlling purpose. From his earliest youth the sense of duty was all-supreme with him; he lived under a constant imperative—in awe of, and in reverent obedience to, the will of a sovereign God; and his theology is but the translation into language of that experience; its translation by one of the world's greatest masters of logical thought and of clear speech.

We have already been told that hardening is not less under the immediate hand of God than mercy. Paul does not, after the example of those whom I have mentioned, labor anxiously to defend God by calling in the aid of falsehood; he only reminds us that it is unlawful for the creature to quarrel with its Creator. Then how will those who refuse to admit that any are reprobated by God, explain the following words of Christ? "Every plant which my heavenly Father hath not planted shall be rooted up" (Matth. xv. 13). They are plainly told that all whom the heavenly Father has not been pleased to plant as sacred trees in his garden are doomed and devoted to destruction. If they deny that this is a sign of reprobation, there is nothing, however clear, that can be proved to them. But if they will still murmur, let us in the soberness of faith rest contented with the admonition of Paul, that it can be no ground of complaint that God, "willing to show his wrath, and to make his power known, endured with much long-suffering the vessels of wrath fitted for destruction: and that he might make known the riches of his glory on the vessels of mercy, which he had afore prepared unto glory" (Rom. ix. 22, 23). Let my readers observe that Paul, to cut off all handle for murmuring and detraction, attributes supreme sovereignty to the wrath and power of God; for it were unjust that those profound judgments which transcend all our powers of discernment should be subjected to our calculation.

Second Period (1385-1521), Spanish influence. Instead of the Provençal style, the courtly circles now began to cultivate the native popular forms, the copla and quadra, and to compose in the dialect of Castile, which communicated to them the influence of the Italian Renaissance, with the vision and allegory of Dante and a fuller understanding of classical antiquity. These two literary currents became the formative elements of the second poetic school of an aristocratic character in Portugal, at the courts of Alphonse V. (1438-1481), John II. (1481-95), and Emanuel (1495-1521), whose works were collected by the poet Garcia de Resende in the 'Cancioneiro Geral' (Lisbon, 1516).

Carlyle's life was a struggle and a warfare. Each of his books was wrenched from him, like the tale of the 'Ancient Mariner,' by a spiritual agony. The early books excited the wrath of his contemporaries, when they were not ridiculed as the grotesque outpourings of an eccentric humorist. His teaching was intended to oppose what most people take to be the general tendency of thought, and yet many who share that tendency gladly acknowledge that they owe to Carlyle a more powerful intellectual stimulus than they can attribute even to their accepted teachers. I shall try briefly to indicate the general nature of his message to mankind, without attempting to consider the soundness or otherwise of particular views.

O evening sun of July, how, at this hour, thy beams fall slant on reapers amid peaceful woody fields; on old women spinning in cottages; on ships far out on the silent main; on Balls at the Orangerie of Versailles, where high-rouged Dames of the Palace are even now dancing with double-jacketed Hussar-Officers;—and also on this roaring Hell-porch of a Hôtel-de-Ville! Babel Tower, with the confusion of tongues, were not Bedlam added with the conflagration of thoughts, was no type of it. One forest of distracted steel bristles, endless, in front of an Electoral Committee; points itself, in horrid radii, against this and the other accused breast. It was the Titans warring with Olympus; and they, scarcely crediting it, have conquered; prodigy of prodigies; delirious,—as it could not but be. Denunciation, vengeance; blaze of triumph on a dark ground of terror; all outward, all inward things fallen into one general wreck of madness!

Besides his 'Memoirs' he also wrote treatises on the goldsmith's art and on sculpture, with especial reference to bronze-founding. They are of great value as manuals of the craftsmanship of the Renaissance, and excellent specimens of good Italian style as applied to technical exposition. And like all cultivated artists of his time Cellini also tried his hand at poetry; but his lack of technical training as a writer comes out even more in his verse than in his prose. The life of Benvenuto was one of incessant activity, laying hold of the whole domain of the plastic arts: of restless wanderings from place to place; and of rash deeds of violence. He lived to the full the life of his age, in all its glory and all its recklessness. As the most famous goldsmith of his time, he worked for all the great personages of the day, and put himself on a footing of familiar acquaintance with popes and princes. As an artist he came into contact with all the phases of Italian society, since a passion for external beauty was at that time the heritage of the Italian people, and art bodied forth the innermost life of the period. Furniture, plate, and personal adornments were not turned out wholesale by machinery as they are to-day, but engaged the individual attention of the most skilled craftsmen. The memory and the traditions of Raphael Sanzio were still cherished by his pupils when Cellini first came to Rome into the brilliant circle of Giulio Romano and his friends; Michelangelo's frescoes were studied with rapturous admiration by the young Benvenuto, and later on he proudly recorded some words of praise of the mighty genius whom he worshiped; and at this time, too, Titian and Tintoretto set the heart of Venice aglow with the splendor and color of their marvelous canvases. The contemporary though not the peer of those masters of the brush and the chisel, Cellini, endowed with a keen feeling for beauty, a dexterous hand, and a lively imagination, in his versatility reached out toward a wider sphere of activity, and laid hold of life at more points, than they.

"I go with him!" said the youth. "Nay, God forbid! no, señor, not for the world; for once alone with me, he would flay me like a Saint Bartholomew."

ohn Calvin was born in the village of Noyon, in northeastern France, on the 10th of July, 1509. He was intended by his parents for the priesthood, for which he seemed to be peculiarly fitted by his naturally austere disposition, averse to every form of sport or frivolity, and he was given an excellent education with that calling in view; but finally at the command of his father—whose plans for his son had undergone a change—he gave up his theological preparation and devoted himself to the study of law. Gifted with an extraordinary memory, rare insight, and an uncommonly keen reasoning faculty, he speedily distinguished himself in his new field, and a brilliant career was predicted for him by his teachers. His tastes however were more literary than legal, and his first published work, written at the age of twenty-three, was a commentary on Seneca's 'De Clementia,' which brought him wide repute as a classical scholar and as a clear and forceful writer.

Though he had apparently renounced forever all thoughts of a clerical life, he retained, even while he was engaged in the study of law and in the more congenial pursuit of literature, his early love for theology; and in 1532, under the influence of some of Luther's writings which happened to fall into his hands, he was converted to the Protestant faith and threw in his fortunes with the little evangelical party in Paris. His intellectual attainments made him a marked man wherever he went, and he speedily became the leading spirit in the circle to which he had attached himself. Compelled soon afterward by the persecuting measures of King Francis I. to flee the country, he took up his residence at Basle and settled down, as he hoped, to a quiet literary life. It was during his stay here that he published in 1536 the first edition of his greatest work, 'The Christian Institutes,' in which is contained the system of theology which has for centuries borne his name, and by which he is best known to the world at large. Probably no other work written by so young a man has ever produced such a wide-spread, profound, and lasting influence. In its original form, it is true, the work was only a brief and simple introduction to the study of the Scriptures, much less imposing and forbidding than the elaborate body of divinity which is now known to theologians as 'Calvin's Institutes': but all the substance of the last edition is to be found in the first; the theology of the one is the theology of the other—the Calvin of 1559 is the Calvin of 1536. The fact that at the age of twenty-six Calvin could publish a system of theology at once so original and so profound—a system, moreover, which with all his activity of intellect and love of truth he never had occasion to modify in any essential particular—is one of the most striking phenomena in the history of the human mind; and yet it is but one of many illustrations of the man's marvelous clearness and comprehensiveness of vision, and of his force and decision of character. His life from beginning to end was the consistent unfolding of a single dominant principle—the unwavering pursuit of a single controlling purpose. From his earliest youth the sense of duty was all-supreme with him; he lived under a constant imperative—in awe of, and in reverent obedience to, the will of a sovereign God; and his theology is but the translation into language of that experience; its translation by one of the world's greatest masters of logical thought and of clear speech.

Calvin's great work was accompanied by a dedicatory epistle addressed to King Francis I., which is by common consent one of the finest specimens of courteous and convincing apology in existence. A brief extract from it will be found in the selections given below.

JOHN CALVIN.

Soon after the publication of the 'Institutes,' Calvin's plans for a quiet literary career were interrupted by a peremptory call to assist in the work of reforming the Church and State of Geneva; and the remainder of his life, with the exception of a brief interval of exile, was spent in that city, at the head of a religious movement whose influence was ultimately felt throughout all Western Europe. It is true that Calvin was not the originating genius of the Reformation—that he belonged only to the second generation of reformers, and that he learned the Protestant faith from Luther. But he became for the peoples of Western Europe what Luther was for Germany, and he gave his own peculiar type of Protestantism—that type which was congenial to his disposition and experience—to Switzerland, to France, to the Netherlands, to Scotland, and through the Dutch, the English Puritans, and the Scotch Presbyterians, to large portions of the New World. Calvin, to be sure, is not widely popular to-day even in those lands which owe him most, for he had little of that human sympathy which glorifies the best thought and life of the present age; but for all that, he has left his mark upon the world, and his influence is not likely ever to be wholly outgrown. His emphasis upon God's holiness made his followers scrupulously, even censoriously pure; his emphasis upon God's will made them stern and unyielding in the performance of what they believed to be their duty; his emphasis upon God's majesty, paradoxical though it may seem at first sight, promoted in no small degree the growth of civil and religious liberty, for it dwarfed all mere human authority and made men bold to withstand the unlawful encroachments of their fellows. Thus Calvin became a mighty force in the world, though he gave the world far more of law than of gospel, far more of Moses than of Christ.

Calvin's career as a writer began at an early day and continued until his death. His pen was a ready one and was seldom idle. In the midst of the most engrossing cares and occupations—the cares and occupations of a preacher, a pastor, a teacher of theology, a statesman, and a reformer to whom the Protestants of many lands looked for inspiration and for counsel—he found time, though he died at the early age of fifty-four, to produce works that to-day fill more than threescore volumes, and all of which bear the unmistakable impress of a great mind. In addition to his 'Institutes,' theological and ethical tracts, and treatises, sermons, and epistles without number, he wrote commentaries upon almost all the books of the Bible; which for lucidity, for wide and accurate learning, and for sound and ripe judgment, have never been surpassed. Among the most characteristic and important of his briefer works are his vigorous and effective 'Reply to Cardinal Sadolet,' who had endeavored after Calvin's exile from Geneva in 1539 to win back the Genevese to the Roman Church; his tract on 'The Necessity of Reforming the Church; presented to the Imperial Diet at Spires, A.D. 1544, in the cause of all who wish with Christ to reign'—an admirable statement of the conditions which had made a reformation of the Church imperatively necessary, and had led to the great religious and ecclesiastical revolution; another tract on 'The True Method of Giving Peace to Christendom and Reforming the Church,'—marked by a beautiful Christian spirit and permeated with sound practical sense; still another containing 'Articles Agreed Upon by the Faculty of Sacred Theology at Paris, with the Antidote', and finally an 'Admonition Showing the Advantages which Christendom might Derive from an Inventory of Relics.' Though Calvin was from boyhood up of a most serious turn of mind, and though his writings, in marked contrast to the writings of Luther, exhibit few if any traces of genial spontaneous humor, the last two works show that he knew how to employ satire on occasion in a very telling way for the overthrow of error and for the discomfiture of his opponents.

In addition to the services which Calvin rendered by his writings to the cause of Christianity and of sacred learning, must be recognized the lasting obligation under which as an author he put his mother tongue. Whether he wrote in Latin or in French, his style was always chaste, elegant, clear, and vigorous. His Latin compares favorably with the best models of antiquity; his French is a new creation. The latter language indeed owes almost as much to Calvin as the German language owes to Luther. He was unquestionably its greatest master in the sixteenth century, and he did more than any one else to fix its permanent character—to give it that exactness, that lucidity, that purity and harmony of which it justly boasts.

Calvin's writings bear throughout the imprint of his character. There appears in all of them the same horror of impurity and dishonor, the same stern sense of duty, the same respect for the sovereignty of the Almighty, the same severe judgment of human failings. To read them is to breathe the tonic air of snow-clad heights; but they are seldom if ever touched with the tender glow of human feeling or transfigured with the radiance of creative imagination. There is that in David, in Isaiah, in Paul, in Luther, which appeals to every heart and makes their words immortal; but Calvin was neither poet nor prophet,—the divine afflatus was not his,—and it is not without reason that his writings, vigorous, forceful, profound, as is their context, and pure and elegant as is their style, are read to-day only by theologians or historians.

PREFATORY ADDRESS TO THE 'INSTITUTES'

To Francis, King of the French, the most Christian Majesty, the most Mighty and Illustrious Monarch, his Sovereign,—John Calvin prays peace and salvation in Christ.

Sire:—When I first engaged in this work, nothing was further from my thoughts than to write what should afterwards be presented to your Majesty. My intention was only to furnish a kind of rudiments, by which those who feel some interest in religion might be trained to true godliness. And I toiled at the task chiefly for the sake of my countrymen the French, multitudes of whom I perceived to be hungering and thirsting after Christ, while very few seemed to have been duly imbued with even a slender knowledge of him. That this was the object which I had in view is apparent from the work itself, which is written in a simple and elementary form, adapted for instruction.

But when I perceived that the fury of certain bad men had risen to such a height in your realm that there was no place in it for sound doctrine, I thought it might be of service if I were in the same work both to give instruction to my countrymen, and also lay before your Majesty a Confession, from which you may learn what the doctrine is that so inflames the rage of those madmen who are this day with fire and sword troubling your kingdom. For I fear not to declare that what I have here given may be regarded as a summary of the very doctrine which, they vociferate, ought to be punished with confiscation, exile, imprisonment, and flames, as well as exterminated by land and sea.

I am aware indeed how, in order to render our cause as hateful to your Majesty as possible, they have filled your ears and mind with atrocious insinuations; but you will be pleased of your clemency to reflect that neither in word nor deed could there be any innocence, were it sufficient merely to accuse. When any one, with the view of exciting prejudice, observes that this doctrine of which I am endeavoring to give your Majesty an account has been condemned by the suffrages of all the estates, and was long ago stabbed again and again by partial sentences of courts of law, he undoubtedly says nothing more than that it has sometimes been violently oppressed by the power and faction of adversaries, and sometimes fraudulently and insidiously overwhelmed by lies, cavils, and calumny. While a cause is unheard, it is violence to pass sanguinary sentences against it; it is fraud to charge it, contrary to its deserts, with sedition and mischief.

That no one may suppose we are unjust in thus complaining, you yourself, most illustrious Sovereign, can bear us witness with what lying calumnies it is daily traduced in your presence; as aiming at nothing else than to wrest the sceptres of kings out of their hands, to overturn all tribunals and seats of justice, to subvert all order and government, to disturb the peace and quiet of society, to abolish all laws, destroy the distinctions of rank and property, and in short turn all things upside down. And yet that which you hear is but the smallest portion of what is said; for among the common people are disseminated certain horrible insinuations—insinuations which, if well founded, would justify the whole world in condemning the doctrine with its authors to a thousand fires and gibbets. Who can wonder that the popular hatred is inflamed against it, when credit is given to those most iniquitous accusations? See why all ranks unite with one accord in condemning our persons and our doctrine!

Carried away by this feeling, those who sit in judgment merely give utterance to the prejudices which they have imbibed at home, and think they have duly performed their part if they do not order punishment to be inflicted on any one until convicted, either on his own confession, or on legal evidence. But of what crime convicted? "Of that condemned doctrine," is the answer. But with what justice condemned? The very evidence of the defense was not to abjure the doctrine itself, but to maintain its truth. On this subject, however, not a whisper is allowed....

It is plain indeed that we fear God sincerely and worship him in truth, since, whether by life or by death, we desire his name to be hallowed; and hatred herself has been forced to bear testimony to the innocence and civil integrity of some of our people, on whom death was inflicted for the very thing which deserved the highest praise. But if any, under pretext of the gospel, excite tumults (none such have as yet been detected in your realm), if any use the liberty of the grace of God as a cloak for licentiousness (I know of numbers who do), there are laws and legal punishments by which they may be punished up to the measure of their deserts; only in the mean time let not the gospel of God be evil spoken of because of the iniquities of evil men.

Sire, that you may not lend too credulous an ear to the accusations of our enemies, their virulent injustice has been set before you at sufficient length: I fear even more than sufficient, since this preface has grown almost to the bulk of a full apology. My object however was not to frame a defense, but only with a view to the hearing of our cause, to mollify your mind, now indeed turned away and estranged from us,—I add, even inflamed against us,—but whose good will, we are confident, we should regain, would you but once with calmness and composure read this our Confession, which we desire your Majesty to accept instead of a defense. But if the whispers of the malevolent so possess your ear that the accused are to have no opportunity of pleading their cause; if those vindictive furies, with your connivance, are always to rage with bonds, scourgings, tortures, maimings, and burnings—we indeed, like sheep doomed to slaughter, shall be reduced to every extremity; yet so that in our patience we will possess our souls, and wait for the strong hand of the Lord, which doubtless will appear in its own time, and show itself armed, both to rescue the poor from affliction and also take vengeance on the despisers, who are now exulting so securely.

Most illustrious King, may the Lord, the King of kings, establish your throne in righteousness and your sceptre in equity.

Basle, August 1st, 1536.

ELECTION AND PREDESTINATION

From the 'Institutes of the Christian Religion'

The human mind when it hears this doctrine of election cannot restrain its petulance, but boils and rages as if aroused by the sound of a trumpet. Many, professing a desire to defend the Deity from an invidious charge, admit the doctrine of election but deny that any one is reprobated (Bernard, in 'Die Ascensionis,' Serm. 2). This they do ignorantly and childishly, since there could be no election without its opposite, reprobation. God is said to set apart those whom he adopts for salvation. It were most absurd to say that he admits others fortuitously, or that they by their industry acquire what election alone confers on a few. Those therefore whom God passes by he reprobates, and that for no other cause but because he is pleased to exclude them from the inheritance which he predestines to his children. Nor is it possible to tolerate the petulance of men in refusing to be restrained by the word of God, in regard to his incomprehensible counsel, which even angels adore.

We have already been told that hardening is not less under the immediate hand of God than mercy. Paul does not, after the example of those whom I have mentioned, labor anxiously to defend God by calling in the aid of falsehood; he only reminds us that it is unlawful for the creature to quarrel with its Creator. Then how will those who refuse to admit that any are reprobated by God, explain the following words of Christ? "Every plant which my heavenly Father hath not planted shall be rooted up" (Matth. xv. 13). They are plainly told that all whom the heavenly Father has not been pleased to plant as sacred trees in his garden are doomed and devoted to destruction. If they deny that this is a sign of reprobation, there is nothing, however clear, that can be proved to them. But if they will still murmur, let us in the soberness of faith rest contented with the admonition of Paul, that it can be no ground of complaint that God, "willing to show his wrath, and to make his power known, endured with much long-suffering the vessels of wrath fitted for destruction: and that he might make known the riches of his glory on the vessels of mercy, which he had afore prepared unto glory" (Rom. ix. 22, 23). Let my readers observe that Paul, to cut off all handle for murmuring and detraction, attributes supreme sovereignty to the wrath and power of God; for it were unjust that those profound judgments which transcend all our powers of discernment should be subjected to our calculation.

It is frivolous in our opponents to reply that God does not altogether reject those whom in lenity he tolerates, but remains in suspense with regard to them, if peradventure they may repent; as if Paul were representing God as patiently waiting for the conversion of those whom he describes as fitted for destruction. For Augustine, rightly expounding this passage, says that where power is united to endurance, God does not permit, but rules (August. Cont. Julian., Lib. v., c. 5). They add also, that it is not without cause the vessels of wrath are said to be fitted for destruction, and that God is said to have prepared the vessels of mercy, because in this way the praise of salvation is claimed for God; whereas the blame of perdition is thrown upon those who of their own accord bring it upon themselves. But were I to concede that by the different forms of expression Paul softens the harshness of the former clause, it by no means follows that he transfers the preparation for destruction to any other cause than the secret counsel of God. This indeed is asserted in the preceding context, where God is said to have raised up Pharaoh, and to harden whom he will. Hence it follows that the hidden counsel of God is the cause of hardening. I at least hold with Augustine, that when God makes sheep out of wolves he forms them again by the powerful influence of grace, that their hardness may thus be subdued; and that he does not convert the obstinate, because he does not exert that more powerful grace, a grace which he has at command if he were disposed to use it (August, de Prædest. Sanct., Lib. i., c. 2)....

SEPTUAGINT. Facsimile, somewhat reduced, of a page of the VATICAN MANUSCRIPT. Fourth Century. Vatican Library. The Septuagint is the Greek translation, by seventy elders, of the Hebrew Bible.

The earlier copies are all in uncial or "capital" letters, cursive or "lower-case" letters being a later invention.

This is a good specimen of the hand-work of the ecclesiastical scribes of the fourth century.

Accordingly, when we are accosted in such terms as these: Why did God from the first predestine some to death, when as they were not yet in existence, they could not have merited sentence of death?—let us by way of reply ask in our turn, What do you imagine that God owes to man, if he is pleased to estimate him by his own nature? As we are all vitiated by sin, we cannot but be hateful to God, and that not from tyrannical cruelty, but the strictest justice. But if all whom the Lord predestines to death are naturally liable to sentence of death, of what injustice, pray, do they complain? Should all the sons of Adam come to dispute and contend with their Creator, because by his eternal providence they were before their birth doomed to perpetual destruction: when God comes to reckon with them, what will they be able to mutter against this defense? If all are taken from a corrupt mass, it is not strange that all are subject to condemnation. Let them not therefore charge God with injustice, if by his eternal judgment they are doomed to a death to which they themselves feel that, whether they will or not, they are drawn spontaneously by their own nature. Hence it appears how perverse is this affectation of murmuring, when of set purpose they suppress the cause of condemnation which they are compelled to recognize in themselves, that they may lay the blame upon God. But though I should confess a hundred times that God is the author (and it is most certain that he is), they do not however thereby efface their own guilt, which, engraven on their own consciences, is ever and anon presenting itself to their view....

If God merely foresaw human events, and did not also arrange and dispose of them at his pleasure, there might be room for agitating the question, how far his foreknowledge amounts to necessity; but since he foresees the things which are to happen, simply because he has decreed that they are so to happen, it is vain to debate about prescience, while it is clear that all events take place by his sovereign appointment.

They deny that it is ever said in distinct terms, God decreed that Adam should perish by his revolt. As if the same God who is declared in Scripture to do whatsoever he pleases could have made the noblest of his creatures without any special purpose. They say that, in accordance with free will, he was to be the architect of his own fortune; that God had decreed nothing but to treat him according to his desert. If this frigid fiction is received, where will be the omnipotence of God, by which, according to his secret counsel on which everything depends, he rules over all? But whether they will allow it or not, predestination is manifest in Adam's posterity. It was not owing to nature that they all lost salvation by the fault of one parent. Why should they refuse to admit with regard to one man that which against their will they admit with regard to the whole human race? Why should they in caviling lose their labor? Scripture proclaims that all were, in the person of one, made liable to eternal death. As this cannot be ascribed to nature, it is plain that it is owing to the wonderful counsel of God. It is very absurd in these worthy defenders of the justice of God to strain at a gnat and swallow a camel. I again ask how it is that the fall of Adam involves so many nations with their infant children in eternal death without remedy, unless that it so seemed meet to God? Here the most loquacious tongues must be dumb. The decree, I admit, is dreadful; and yet it is impossible to deny that God foreknew what the end of man was to be before he made him, and foreknew because he had so ordained by his decree. Should any one here inveigh against the prescience of God, he does it rashly and unadvisedly. For why, pray, should it be made a charge against the heavenly Judge, that he was not ignorant of what was to happen? Thus, if there is any just or plausible complaint, it must be directed against predestination. Nor ought it to seem absurd when I say that God not only foresaw the fall of the first man, and in him the ruin of his posterity, but also at his own pleasure arranged it. For as it belongs to his wisdom to foreknow all future events, so it belongs to his power to rule and govern them by his hand.

FREEDOM OF THE WILL

From the 'Institutes of the Christian Religion'

God has provided the soul of man with intellect, by which he might discern good from evil, just from unjust, and might know what to follow or to shun, reason going before with her lamp; whence philosophers, in reference to her directing power, have called her [Greek: to hêgemonichon]. To this he has joined will, to which choice belongs. Man excelled in these noble endowments in his primitive condition, when reason, intelligence, prudence, and judgment not only sufficed for the government of his earthly life, but also enabled him to rise up to God and eternal happiness. Thereafter choice was added to direct the appetites and temper all the organic motions; the will being thus perfectly submissive to the authority of reason. In this upright state, man possessed freedom of will, by which if he chose he was able to obtain eternal life. It were here unseasonable to introduce the question concerning the secret predestination of God, because we are not considering what might or might not happen, but what the nature of man truly was. Adam, therefore, might have stood if he chose, since it was only by his own will that he fell; but it was because his will was pliable in either direction, and he had not received constancy to persevere, that he so easily fell. Still he had a free choice of good and evil; and not only so, but in the mind and will there was the highest rectitude, and all the organic parts were duly framed to obedience, until man corrupted its good properties, and destroyed himself. Hence the great darkness of philosophers who have looked for a complete building in a ruin, and fit arrangement in disorder. The principle they set out with was, that man could not be a rational animal unless he had a free choice of good and evil. They also imagined that the distinction between virtue and vice was destroyed, if man did not of his own counsel arrange his life. So far well, had there been no change in man. This being unknown to them, it is not surprising that they throw everything into confusion. But those who, while they profess to be the disciples of Christ, still seek for free-will in man, notwithstanding of his being lost and drowned in spiritual destruction, labor under manifold delusion, making a heterogeneous mixture of inspired doctrine and philosophical opinions, and so erring as to both. But it will be better to leave these things to their own place. At present it is necessary only to remember that man at his first creation was very different from all his posterity; who, deriving their origin from him after he was corrupted, received a hereditary taint. At first every part of the soul was formed to rectitude. There was soundness of mind and freedom of will to choose the good. If any one objects that it was placed, as it were, in a slippery position because its power was weak, I answer, that the degree conferred was sufficient to take away every excuse. For surely the Deity could not be tied down to this condition,—to make man such that he either could not or would not sin. Such a nature might have been more excellent; but to expostulate with God as if he had been bound to confer this nature on man, is more than unjust, seeing he had full right to determine how much or how little he would give. Why he did not sustain him by the virtue of perseverance is hidden in his counsel; it is ours to keep within the bounds of soberness. Man had received the power, if he had the will, but he had not the will which would have given the power; for this will would have been followed by perseverance. Still, after he had received so much, there is no excuse for his having spontaneously brought death upon himself. No necessity was laid upon God to give him more than that intermediate and even transient will, that out of man's fall he might extract materials for his own glory.

LUIZ VAZ DE CAMOENS

(1524?-1580)

BY HENRY R. LANG

ortuguese literature is usually divided into six periods, which correspond, in the main, to the successive literary movements of the other Romance nations which it followed.

First Period (1200-1385), Provençal and French influences. Soon after the founding of the Portuguese State by Henry of Burgundy and his knights in the beginning of the twelfth century, the nobles of Portugal and Galicia, which regions form a unit in race and speech, began to imitate in their native idiom the art of the Provençal troubadours who visited the courts of Leon and Castile. This courtly lyric poetry in the Gallego-Portuguese dialect, which was also cultivated in the rest of the peninsula excepting the East, reached its height under Alphonso X. of Castile (1252-84), himself a noted poet and patron of this art, and under King Dionysius of Portugal (1279-1325), the most gifted of all these troubadours. The collections (cancioneiros) of the works of this school preserved to us contain the names of one hundred and sixty-three poets and some two thousand compositions (inclusive of the four hundred and one spiritual songs of Alphonso X.). Of this body of verse, two-thirds affect the artificial style of Provençal lyrics, while one-third is derived from the indigenous popular poetry. This latter part contains the so-called cantigas de amigo, songs of charming simplicity of form and naïveté of spirit in which a woman addresses her lover either in a monologue or in a dialogue. It is this native poetry, still echoed in the modern folk-song of Galicia and Portugal, that imparted to the Gallego-Portuguese lyric school the decidedly original coloring and vigorous growth which assign it an independent position in the mediæval literature of the Romance nations.

Composition in prose also began in this period, consisting chiefly in genealogies, chronicles, and in translations from Latin and French dealing with religious subjects and the romantic traditions of British origin, such as the 'Demanda do Santo Graal.' It is now almost certain that the original of the Spanish version of the 'Amadis de Gaula' (1480) was the work of a Portuguese troubadour of the thirteenth century, Joam de Lobeira.

Second Period (1385-1521), Spanish influence. Instead of the Provençal style, the courtly circles now began to cultivate the native popular forms, the copla and quadra, and to compose in the dialect of Castile, which communicated to them the influence of the Italian Renaissance, with the vision and allegory of Dante and a fuller understanding of classical antiquity. These two literary currents became the formative elements of the second poetic school of an aristocratic character in Portugal, at the courts of Alphonse V. (1438-1481), John II. (1481-95), and Emanuel (1495-1521), whose works were collected by the poet Garcia de Resende in the 'Cancioneiro Geral' (Lisbon, 1516).

The prose-literature of this period is rich in translations from the Latin classics, and chiefly noteworthy for the great Portuguese chronicles which it produced. The most prominent writer was Fernam Lopes (1454), the founder of Portuguese historiography and the "father of Portuguese prose."

Third Period (1521-1580), Italian influence. This is the classic epoch of Portuguese literature, born of the powerful rise of the Portuguese State during its period of discovery and conquest, and of the dominant influence of the Italian Renaissance. It opens with three authors who were prominently active in the preceding literary school, but whose principal influence lies in this. These are Christovam Falcão and Bernardim Ribeiro, the founders of the bucolic poem and the sentimental pastoral romance, and Gil Vicente, a comic writer of superior talent, who is called the father of the Portuguese drama, and who, next to Camoens, is the greatest figure of this period. Its real initiator, however, was Francesco Sa' de Miranda (1495-1557) who, on his return from a six-years' study in Italy in 1521, introduced the lyric forms of Petrarch and his followers as the only true models for composition. Besides giving by his example a classic form to lyrics, especially to the sonnet, and cultivating the pastoral poem, Sa' de Miranda, desirous of breaking the influence of Gil Vicente's dramas, wrote two comedies of intrigue in the style of the Italians and of Plautus and Terence. His attempts in this direction, however, found no followers, the only exception being Ferreira's tragedy 'Ines de Castro' in the antique style. The greatest poet of this period, and indeed in the whole history of Portuguese literature, is Luiz de Camoens, in whose works, epic, lyric, and dramatic, the cultivation of the two literary currents of this epoch, the national and the Renaissance, attained to its highest perfection, and to whom Portuguese literature chiefly owes its place in the literature of the world.

Among the works in prose produced during this time are of especial importance the historical writings, such as the 'Décadas' of João de Barros (1496-1570), the "Livy of Portugal" and the numerous romances of chivalry.

LUIS DE CAMOËNS.

Fourth Period (1580-1700), Culteranistic influence. The political decline of Portugal is accompanied by one in its literature. While some lyric poetry is still written in the spirit of Camoens, and the pastoral romance in the national style is cultivated by some authors, Portuguese literature on the whole is completely under the influence of the Spanish, receiving from the latter the euphuistic movement, known in Spain as culteranismo or Gongorismo. Many writers of talent of this time used the Spanish language in preference to their own. It is thus that the charming pastoral poem 'Diana,' by Jorge de Montemor, though composed by a Portuguese and in a vein so peculiar to his nation, is credited to Spanish literature.

Fifth Period (1700-1825), Pseudo-Classicism. The influence of the French classic school, felt in all European literatures, became paramount in Portugal. Excepting the works of a few talented members of the society called "Arcadia," little of literary interest was produced until the appearance, at the end of the century, of Francisco Manoel de Nascimento and Manoel Maria Barbosa du Bocage, two poets of decided talent who connect this period with the following.

Sixth Period (since 1825), Romanticism. The initiator of this movement in Portugal was Almeida-Garrett (1799-1854), with Gil Vicente and Camoens one of the three great poets Portugal has produced, who revived and strengthened the sense of national life in his country by his 'Camoens,' an epic of glowing patriotism published during his exile in 1825, by his national dramas, and by the collection of the popular traditions of his people, which he began and which has since been zealously continued in all parts of the country. The second influential leader of romanticism was Alexandre Herculano (1810-1877), great especially as national historian, but also a novelist and poet of superior merit. The labors of these two men bore fruit, since the middle of the century, in what may be termed an intellectual renovation of Portugal which first found expression in the so-called Coimbra School, and has since been supported by such men as Theophilo Braga, F. Adolpho Coelho, Joaquim de Vasconcellos, J. Leite de Vasconcellos, and others, whose life-work is devoted to the conviction that only a thorough and critical study of their country's past can inspire its literature with new life and vigor and maintain the sense of national independence.

Luiz Vaz De Camoens, Portugal's greatest poet and patriot, was born in 1524 or 1525, most probably at Coimbra, as the son of Simão Vaz de Camoens and Donna Anna de Macedo of Santarem. Through his father, a cavalleiro fidalgo, or untitled nobleman, who was related with Vasco da Gama, Camoens descended from an ancient and once influential noble family of Galician origin. He spent his youth at Coimbra, and though his name is not found in the registers of the university, which had been removed to that city in 1537, and of which his uncle, Bento de Camoens, prior of the monastery of Santa Cruz, was made chancellor in 1539, it was presumably in that institution, then justly famous, that the highly gifted youth acquired his uncommon familiarity with the classics and with the literatures of Spain, Italy, and that of his own country. In 1542 we find Camoens exchanging his alma mater for the gay and brilliant court of John III., then at Lisbon, where his gentle birth, his poetic genius, and his fine personal appearance brought him much favor, especially with the fair sex, while his independent bearing and indiscreet speech aroused the jealousy and enmity of his rivals. Here he woos and wins the damsels of the palace until a high-born lady in attendance upon the Queen, Donna Catharina de Athaide,—whom, like Petrarch, he claims to have first seen on Good Friday in church, and who is celebrated in his poems under the anagram of Natercia,—inspires him with a deep and enduring passion. Irritated by the intrigues employed by his enemies to mar his prospects, the impetuous youth commits imprudent acts which lead to his banishment from the city in 1546. For about a year he lives in enforced retirement on the Upper Tagus (Ribatejo), pouring out his profound passion and grief in a number of beautiful sonnets and elegies. Most likely in consequence of some new offense, he is next exiled for two years to Ceuta in Africa, where, in a fight with the Moors, he loses his right eye by a chance splinter. Meeting on his return to Lisbon in 1547 neither with pardon for his indiscretions nor with recognition for his services and poetic talent, he allows his keen resentment of this unjust treatment to impel him into the reckless and turbulent life of a bully. It was thus that during the festival of Corpus Christi in 1552 he got into a quarrel with Gonçalo Borges, one of the King's equerries, in which he wounded the latter. For this Camoens was thrown into jail until March, 1553, when he was released only on condition that he should embark to serve in India. Not quite two weeks after leaving his prison, on March 24th, he sailed for India on the flag-ship Sam Bento, bidding, as a true Renaissance poet, farewell to his native land in the words of Scipio which were to come true: "Ingrata patria non possidebis ossa mea." After a stormy passage of six months, the Sam Bento cast anchor in the bay of Goa. Camoens first took part in an expedition against the King of Pimenta, and in the following year (1554) he joined another directed against the Moorish pirates on the coast of Africa. The scenes of drunkenness and dissoluteness which he witnessed in Goa inspired him with a number of satirical poems, by which he drew upon himself much enmity and persecution. In 1556 his three-years' term of service expired; but though ardently longing for his beloved native land, he remained in Goa, influenced either by his bent for the soldier's life or by the sad news of the death of Donna Catharina de Athaide in that year. He was ordered to Macao in China, to the lucrative post of commissary for the effects of deceased or absent Portuguese subjects. There, in the quietude of a grotto near Macao, still called the Grotto of Camoens, the exiled poet finished the first six cantos of his great epic 'The Lusiads.' Recalled from this post in 1558, before the expiration of his term, on the charge of malversation of office, Camoens on his return voyage to Goa was shipwrecked near the mouth of the Me-Kong, saving nothing but his faithful Javanese slave and the manuscript of his 'Lusiads'—which, swimming with one hand, he held above the water with the other. In Cambodia, where he remained several months, he wrote his marvelous paraphrase of the 137th psalm, contrasting under the allegory of Babel (Babylon) and Siam (Zion), Goa and Lisbon. Upon his return to Goa he was cast into prison, but soon set free on proving his innocence by a public trial. Though receiving, in 1557, another lucrative employment, Camoens finally resolved to go home, burning with the desire to lay his patriotic song, now almost completed, before his nation, and to cover with honor his injured name.

He accepted a passage to Sofala offered him by Pedro Barreto, who had become viceroy of Mozambique in that year. Unable to refund the amount of the passage, he was once more held for debt and spent two years of misery and distress in Mozambique, completing and polishing during this time his great epic song and preparing the collection of his lyrics, his 'Parnasso.' In 1559 he was released by the historian Diogo do Couto and other friends of his, visiting Sofala with the expedition of Noronha, and embarked on the Santa Clara for Lisbon.

On the 7th of April, 1570, Camoens once more set foot on his native soil, only to find the city for which he had yearned, sadly changed. The government was in the hands of a brave but harebrained and fanatic young monarch, ruled by the Jesuits; the capital had been ravaged by a terrible plague which had carried off fifty thousand souls; and its society had no room for a man who brought with him from the Indies, whence so many returned with great riches, nothing but a manuscript, though in it was sung in classic verse the glory of his people. Still, through the kind offices of his warm friend Dom Manoel de Portugal, Camoens obtained, on the 25th of September, 1571, the royal permission to print his epic. It was published in the spring of the following year (March, 1572). Great as was the success of the work, which marked a new epoch in Portuguese history, the reward which the poet received for it was meagre. King Sebastian granted him an annual pension of fifteen thousand reis (fifteen dollars, which then had the purchasing value of about sixty dollars in our money), which, after the poet's death, was ordered by Philip II. to be paid to his aged mother. Destitute and broken in spirit, Camoens lived for the last eight years of his life with his mother in a humble house near the convent of Santa Ana, "in the knowledge of many and in the society of few." Dom Sebastian's departure early in 1578 for the conquest in Africa once more kindled patriotic hopes in his breast; but the terrible defeat at Alcazarquivir (August 4th of the same year), in which Portugal lost her king and her army, broke his heart. He died on the 10th of June, 1580, at which time the army of Philip II., under the command of the Duke of Alva, was marching upon Lisbon. He was thus spared the cruel blow of seeing, though not of foreseeing, the national death of his country. The story that his Javanese slave Antonio used to go out at night to beg of passers-by alms for his master, is one of a number of touching legends which, as early as 1572, popular fancy had begun to weave around the poet's life. It is true, however, that Camoens breathed his last in dire distress and isolation, and was buried "poorly and plebeianly" in the neighboring convent of Santa Ana. It was not until sixteen years later that a friend of his, Dom Gonçalo Coutinho, caused his grave to be marked with a marble slab bearing the inscription:—"Here lies Luis de Camoens, Prince of the Poets of his time. He died in the year 1579. This tomb was placed for him by order of D. Gonçalo Coutinho, and none shall be buried in it." The words "He lived poor and neglected, and so died," which in the popular tradition form part of this inscription, are apocryphal, though entirely in conformity with the facts. The correctness of 1580 instead of 1579 as the year of the poet's death is proven by an official document in the archives of Philip II. Both the memorial slab and the convent-church of Santa Ana were destroyed by the earthquake of 1755 and during the rebuilding of the convent, and the identification of the remains of the great man thus rendered well-nigh impossible. In 1854, however, all the bones found under the floor of the convent-church were placed in a coffin of Brazil-wood and solemnly deposited in the convent at Belem, the Pantheon of King Emanuel. In 1867 a statue was erected to Camoens by the city of Lisbon.

'The Lusiads' (Portuguese, Os Lusiadas), a patronymic adopted by Camoens in place of the usual term Lusitanos, the descendants of Lusus (the mythical ancestor of the Portuguese), is an epic poem which, as its name implies, has for its subject the heroic deeds not of one hero, but of the whole Portuguese nation. Vasco da Gama's discovery of the way to the East Indies forms, to be sure, the central part of its action; but around it are grouped, with consummate art, the heroic deeds and destinies of the other Lusitanians. In this, Camoens' work stands alone among all poems of its kind. Originating under conditions similar to those which are indispensable to the production of a true epic, in the heroic period of the Portuguese people, when national sentiment had risen to its highest point, it is the only one among the modern epopees which comes near to the primitive character of epic poetry. A trait which distinguishes this epic from all its predecessors is the historic truthfulness with which Camoens confessedly—"A verdade que eu conto nua e pura Vence toda a grandiloqua escriptura"—represents his heroic personages and their exploits, tempering his praise with blame where blame is due, and the unquestioned fidelity and exactness with which he depicts natural scenes. Lest, however, this adherence to historic truth should impair the vivifying element of imagination indispensable to true poetry, our bard, combining in the true spirit of the Renaissance myth and miracle, threw around his narrative the allegorical drapery of pagan mythology, introducing the gods and goddesses of Olympus as siding with or against the Portuguese heroes, and thus calling the imagination of the reader into more active play. Among the many beautiful inventions of his own creative fancy with which Camoens has adorned his poem, we shall only mention the powerful impersonation of the Cape of Storms in the Giant Adamastor (c. v.), an episode used by Meyerbeer in his opera 'L'Africaine,' and the enchanting scene of the Isle of Love (c. ix.), as characteristic of the poet's delicacy of touch as it is of his Portuguese temperament, in which Venus provides for the merited reward and the continuance of the brave sons of Lusus. For the metric form of his verse, Camoens adopted the octave rhyme of Ariosto, while for his epic style he followed Virgil, from whom many a simile and phrase is directly borrowed. His poem, justly admired for the elegant simplicity, the purity and harmony of its diction, bears throughout the deep imprint of his own powerful and noble personality, that independence and magnanimity of spirit, that fortitude of soul, that genuine and glowing patriotism which alone, amid all the disappointments and dangers, the dire distress and the foibles and faults of his life, could enable him to give his mind and heart steadfastly to the fulfillment of the lofty patriotic task he had set his genius,—the creation of a lasting monument to the heroic deeds of his race. It is thus that through 'The Lusiads' Camoens became the moral bond of the national individuality of his people, and inspired it with the energy to rise free once more out of Spanish subjection.

Lyrics. Here, Camoens is hardly less great than as an epic poet, whether we consider the nobility, depth, and fervor of the sentiments filling his songs, or the artistic perfection, the rich variety of form, and the melody of his verse. His lyric works fall into two main classes, those written in Italian metres and those in the traditional trochaic lines and strophic forms of the Spanish peninsula. The first class is contained in the 'Parnasso,' which comprises 356 sonnets, 22 canzones, 27 elegies, 12 odes, 8 octaves, and 15 idyls, all of which testify to the great influence of the Italian school, and especially of Petrarch, on our poet. The second class is embodied in the 'Cancioneiro,' or song-book, and embraces more than one hundred and fifty compositions in the national peninsular manner. Together, these two collections form a body of lyric verse of such richness and variety as neither Petrarch and Tasso nor Garcilaso de la Vega can offer. Unfortunately, Camoens never prepared an edition of his Rimas; and the manuscript, which, as Diogo do Couto tells us, he arranged during his sojourn in Mozambique from 1567 to 1569, is said to have been stolen. It was not until 1595, fully fifteen years after the poet's death, that one of his disciples and admirers, Fernão Rodrigues Lobo Soropita, collected from Portugal, and even from India, and published in Lisbon, a volume of one hundred and seventy-two songs, four of which, however, are not by Camoens. The great mass of verse we now possess has been gathered during the last three centuries. More may still be discovered, while, on the other hand, much of what is now attributed to Camoens does not belong to him, and the question how much of the extant material is genuine is yet to be definitely answered.

In his lyrics, Camoens has depicted, with all the passion and power of his impressionable temperament, the varied experiences and emotions of his eventful life. This variety and change of sentiments and situations, while greatly enhancing the value of his songs by the impression of fuller truth and individuality which they produce, is in so far disadvantageous to a just appreciation of them, as it naturally brings with it much verse of inferior poetic merit, and lacks that harmony and unity of emotion which Petrarch was able to effect in his Rime by confining himself to the portraiture of a lover's soul.

Drama. In his youth, most likely during his life at court between 1542 and 1546, Camoens wrote three comedies of much freshness and verve, in which he surpassed all the Portuguese plays in the national taste produced up to his time. One, 'Filodemo,' derives its plot from a mediæval novel; the other two, 'Rei Seleuco' (King Seleucus) and 'Amphitryões,' from antiquity. The last named, a free imitation of Plautus's 'Amphitryo,' is by far the best play of the three. In these comedies we can recognize an attempt on the part of the author to fuse the imperfect play in the national taste, such as it had been cultivated by Gil Vicente, with the more regular but lifeless pieces of the classicists, and thus to create a superior form of national comedy. In this endeavor, however, Camoens found no followers.

Bibliography. The most complete edition of the works of Camoens is that by the Viscount de Juromenha, 'Obras de Luiz de Camões,' (6 vols., Lisbon, 1860-70); a more convenient edition is the one by Th. Braga (in 'Bibliotheca da Actualidade,' 3 vols., Porto, 1874). The best separate edition of the text of 'The Lusiads' is by F.A. Coelho (Lisbon, 1880). Camoens' lyric and dramatic works are published in his collected works, no separate editions of them existing thus far. In regard to the life and works of Camoens in general cf. Adamson, 'Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Camoens' (2 vols., London, 1820); Th. Braga, 'Historia de Camoens' (3 vols., Porto, 1873-75); Latino Coelho, 'Luiz de Camoens' (in the 'Galeria de varões illustres,' i., Lisbon, 1880); J. de Vasconcellos, 'Bibliographia Camoniana' (Porto, 1880); Brito Aranha, 'Estudos Bibliographicos' (Lisbon, 1887-8); W. Storck, 'Luis' de Camoens Leben' (Paderborn, 1890); and especially the judicious and impartial article by Mrs. Carolina Michaelis de Vasconcellos in Vol. ii. of Gröber's 'Grundriss der romanischen Philologie' (Strassburg, 1894). The best translations of Camoens' works are the one by W. Storck, 'Camoens' Sämmtliche Gedichte, 6 vols., Paderborn, 1880-85), into German, and the one by R.F. Burton, who has also written on the life of the poet, 'The Lusiads' (2 vols., London, 1880), and 'The Lyricks' (3 vols., London, 1884, containing only those in Italian metres), into English. The extracts given below are from Burton.

THE LUSIADS

Canto I

The feats of Arms, and famed heroick Host, from occidental Lusitanian strand, who o'er the waters ne'er by seaman crost, fared beyond the Taprobane-land, forceful in perils and in battle-post, with more than promised force of mortal hand; and in the regions of a distant race rear'd a new throne so haught in Pride of Place:

And, eke, the Kings of mem'ory grand and glorious, who hied them Holy Faith and Reign to spread, converting, conquering, and in lands notorious, Africk and Asia, devastation made; nor less the Lieges who by deeds memorious brake from the doom that binds the vulgar dead; my song would sound o'er Earth's extremest part were mine the genius, mine the Poet's art.

Cease the sage Grecian, and the man of Troy to vaunt long voyage made in by-gone day: Cease Alexander, Trojan cease to 'joy the fame of vict'ories that have pass'd away: The noble Lusian's stouter breast sing I, whom Mars and Neptune dared not disobey: Cease all that antique Muse hath sung, for now a better Brav'ry rears its bolder brow.

And you, my Tagian Nymphs, who have create in me new purpose with new genius firing; if 'twas my joy whilere to celebrate your founts and stream my humble song inspiring; Oh! lend me here a noble strain elate, a style grandiloquent that flows untiring; so shall Apollo for your waves ordain ye in name and fame ne'er envy Hippokréné.

Grant me sonorous accents, fire-abounding, now serves ne peasant's pipe, ne rustick reed; but blasts of trumpet, long and loud resounding, that 'flameth heart and hue to fiery deed: Grant me high strains to suit their Gestes astounding, your Sons, who aided Mars in martial need; that o'er the world he sung the glorious song, if theme so lofty may to verse belong.

And Thou! O goodly omen'd trust, all-dear[1] to Lusitania's olden liberty, whereon assurèd esperance we rear enforced to see our frail Christianity: Thou, O new terror to the Moorish spear, the fated marvel of our century, to govern worlds of men by God so given, that the world's best be given to God and Heaven:

Thou young, thou tender, ever-flourishing bough, true scion of tree by Christ belovèd more than aught that Occident did ever know, "Cæsarian" or "Most Christian" styled before: Look on thy 'scutcheon, and behold it show the present Vict'ory long past ages bore; Arms which He gave and made thine own to be by Him assurèd on the fatal tree:[2]

Thou, mighty Sovran! o'er whose lofty reign the rising Sun rains earliest smile of light; sees it from middle firmamental plain; And sights it sinking on the breast of Night: Thou, whom we hope to hail the blight, the bane of the dishonour'd Ishmaëlitish knight; and Orient Turk, and Gentoo—misbeliever that drinks the liquor of the Sacred River:[3]

Incline awhile, I pray, that majesty which in thy tender years I see thus ample, E'en now prefiguring full maturity that shall be shrined in Fame's eternal temple: Those royal eyne that beam benignity bend on low earth: Behold a new ensample of hero hearts with patriot pride inflamèd, in number'd verses manifold proclaimèd.

Thou shalt see Love of Land that ne'er shall own lust of vile lucre; soaring towards th' Eternal: For 'tis no light ambition to be known th' acclaimed herald of my nest paternal. Hear; thou shalt see the great names greater grown of Vavasors who hail the Lord Supernal: So shalt thou judge which were the higher station, King of the world or Lord of such a nation.

Hark, for with vauntings vain thou shalt not view phantastical, fictitious, lying deed of lieges lauded, as strange Muses do, seeking their fond and foolish pride to feed Thine acts so forceful are, told simply true, all fabled, dreamy feats they far exceed; exceeding Rodomont, and Ruggiero vain, and Roland haply born of Poet's brain.

For these I give thee a Nuno, fierce in fight, who for his King and Country freely bled; an Egas and a Fuas; fain I might for them my lay with harp Homeric wed! For the twelve peerless Peers again I cite the Twelve of England by Magriço led: Nay, more, I give thee Gama's noble name, who for himself claims all Æneas' fame.

And if in change for royal Charles of France, or rivalling Cæsar's mem'ories thou wouldst trow, the first Afonso see, whose conquering lance lays highest boast of stranger glories low: See him who left his realm th' inheritance fair Safety, born of wars that crusht the foe: That other John, a knight no fear deter'd, the fourth and fifth Afonso, and the third.

Nor shall they silent in my song remain, they who in regions there where Dawns arise, by Acts of Arms such glories toil'd to gain, where thine unvanquisht flag for ever flies, Pacheco, brave of braves; th' Almeidas twain, whom Tagus mourns with ever-weeping eyes; dread Albuquerque, Castro stark and brave, with more, the victors of the very grave.

But, singing these, of thee I may not sing, O King sublime! such theme I fain must fear. Take of thy reign the reins, so shall my King create a poesy new to mortal ear: E'en now the mighty burthen here I ring (and speed its terrors over all the sphere!) of sing'ular prowess, War's own prodigies, in Africk regions and on Orient seas.

Casteth on thee the Moor eyne cold with fright, in whom his coming doom he views designèd: The barb'rous Gentoo, sole to see thy sight yields to thy yoke the neck e'en now inclinèd; Tethys, of azure seas the sovran right, her realm, in dowry hath to thee resignèd; and by thy noble tender beauty won, would bribe and buy thee to become her son.

In thee from high Olympick halls behold themselves, thy grandsires' sprites; far-famèd pair;[4] this clad in Peacetide's angel-robe of gold, that crimson-hued with paint of battle-glare: By thee they hope to see their tale twice told, their lofty mem'ries live again; and there, when Time thy years shall end, for thee they 'sign a seat where soareth Fame's eternal shrine.

But, sithence ancient Time slow minutes by ere ruled the Peoples who desire such boon; bend on my novel rashness favouring eye, that these my verses may become thine own: So shalt thou see thine Argonauts o'erfly yon salty argent, when they see it shown thou seest their labours on the raging sea: Learn even now invok'd of man to be.[5]

Canto III

Now, my Calliope! to teach incline what speech great Gama for the king did frame: Inspire immortal song, grant voice divine unto this mortal who so loves thy name. Thus may the God whose gift was Medicine, to whom thou barest Orpheus, lovely Dame! never for Daphne, Clytia, Leucothoe due love deny thee or inconstant grow he.

Satisfy, Nymph! desires that in me teem, to sing the merits of thy Lusians brave; so worlds shall see and say that Tagus-stream rolls Aganippe's liquor. Leave, I crave, leave flow'ry Pindus-head; e'en now I deem Apollo bathes me in that sovran wave; else must I hold it, that thy gentle sprite, fears thy dear Orpheus fade through me from sight.

All stood with open ears in long array to hear what mighty Gama mote unfold; when, past in thoughtful mood a brief delay, began he thus with brow high-raised and bold:— "Thou biddest me, O King! to say my say anent our grand genealogy of old: Thou bidd'st me not relate an alien story; Thou bidd'st me laud my brother Lusian's glory.

"That one praise others' exploits and renown is honour'd custom which we all desire; yet fear I 'tis unfit to praise mine own; lest praise, like this suspect, no trust inspire; nor may I hope to make all matters known for Time however long were short; yet, sire! as thou commandest all is owed to thee; maugre my will I speak and brief will be.

"Nay, more, what most obligeth me, in fine, is that no leasing in my tale may dwell; for of such Feats whatever boast be mine, when most is told, remaineth much to tell: But that due order wait on the design, e'en as desirest thou to learn full well, the wide-spread Continent first I'll briefly trace, then the fierce bloody wars that waged my race.

"Lo! here her presence showeth noble Spain, of Europe's body corporal the head; o'er whose home-rule, and glorious foreign reign, the fatal Wheel so many a whirl hath made; Yet ne'er her Past or force or fraud shall stain, nor restless Fortune shall her name degrade; no bonds her bellic offspring bind so tight but it shall burst them with its force of sprite.

"There, facing Tingitania's shore, she seemeth to block and bar the Med'iterranean wave, where the known Strait its name ennobled deemeth by the last labour of the Theban Brave. Big with the burthen of her tribes she teemeth, circled by whelming waves that rage and rave; all noble races of such valiant breast, that each may justly boast itself the best.

"Hers the Tarragonese who, famed in war, made aye-perturbed Parthenopé obey; the twain Asturias, and the haught Navarre twin Christian bulwarks on the Moslem way: Hers the Gallego canny, and the rare Castilian, whom his star raised high to sway Spain as her saviour, and his seign'iory feel Bætis, Leon, Granada, and Castile.

"See, the head-crowning coronet is she of general Europe, Lusitania's reign, where endeth land and where beginneth sea, and Phœbus sinks to rest upon the main. Willed her the Heavens with all-just decree by wars to mar th' ignoble Mauritan, to cast him from herself: nor there consent he rule in peace the Fiery Continent.

"This is my happy land, my home, my pride; where, if the Heav'ens but grant the pray'er I pray for glad return and every risk defied, there may my life-light fail and fade away. This was the Lusitania, name applied by Lusus or by Lysa, sons, they say, of antient Bacchus, or his boon compeers, eke the first dwellers of her eldest years.

"Here sprang the Shepherd,[6] in whose name we see forecast of virile might, of virtuous meed; whose fame no force shall ever hold in fee, since fame of mighty Rome ne'er did the deed. This, by light Heaven's volatile decree, that antient Scyther, who devours his seed, made puissant pow'er in many a part to claim, assuming regal rank; and thus it came:—

"A King there was in Spain, Afonso hight, who waged such warfare with the Saracen, that by his 'sanguined arms, and arts, and might, he spoiled the lands and lives of many men. When from Hercùlean Calpè winged her flight his fame to Caucasus Mount and Caspian glen, many a knight, who noblesse coveteth, comes offering service to such King and Death.

"And with intrinsic love inflamèd more for the True Faith, than honours popular, they troopèd, gath'ering from each distant shore, leaving their dear-loved homes and lands afar. When with high feats of force against the Moor they proved of sing'ular worth in Holy War, willèd Afonso that their mighty deeds commens'urate gifts command and equal meeds.

"'Mid them Henrique, second son, men say, of a Hungarian King, well-known and tried, by sort won Portugal which, in his day, ne prizèd was ne had fit cause for pride: His strong affection stronger to display the Spanish King decreed a princely bride, his only child, Teresa, to the count; And with her made him Seigneur Paramount.