автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Library of the World's Best literature, Ancient and Modern, Vol. 12

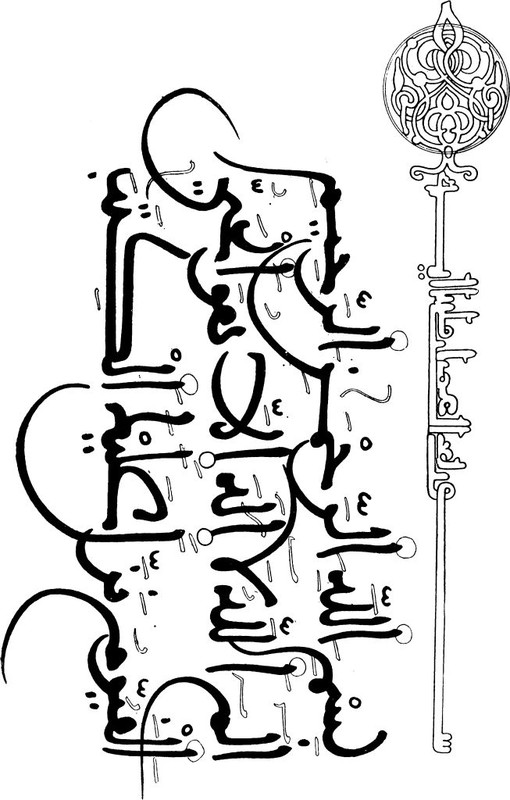

JAVANESE ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPT.

The origin of the Oceanic dialects, and of those of India beyond the Ganges, more especially the civilized idioms of the Indian Archipelago, is referred to a language which was that of an unknown people inhabiting the island of Java. From this primitive language the modern Javanese is supposed to be immediately derived. Javanese literature consists of poems, dramas, songs, and historical and religious writings. The accompanying facsimile is from a mythological-religious tract written upon a vegetable paper of native manufacture, and ornamented with grotesque drawings.

LIBRARY OF THE

WORLD'S BEST LITERATURE

ANCIENT AND MODERN

CHARLES DUDLEY WARNER

EDITOR

HAMILTON WRIGHT MABIE

LUCIA GILBERT RUNKLE

GEORGE HENRY WARNER

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Connoisseur Edition

Vol. XII.

NEW YORK

THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY

Connoisseur Edition

LIMITED TO FIVE HUNDRED COPIES IN HALF RUSSIA

No. ..........

Copyright, 1896, by

R. S. PEALE AND J. A. HILL

All rights reserved

THE ADVISORY COUNCIL

CRAWFORD H. TOY, A. M., LL. D.,

Professor of Hebrew, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

THOMAS R. LOUNSBURY, LL. D., L. H. D.,

Professor of English in the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

WILLIAM M. SLOANE, Ph. D., L. H. D.,

Professor of History and Political Science, Princeton University, Princeton, N. J.

BRANDER MATTHEWS, A. M., LL. B.,

Professor of Literature, Columbia University, New York City.

JAMES B. ANGELL, LL. D.,

President of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.

WILLARD FISKE, A. M., Ph. D.,

Late Professor of the Germanic and Scandinavian Languages and Literatures, Cornell University, Ithaca, N. Y.

EDWARD S. HOLDEN, A. M., LL. D.,

Director of the Lick Observatory, and Astronomer, University of California, Berkeley, Cal.

ALCÉE FORTIER, LIT. D.,

Professor of the Romance Languages, Tulane University, New Orleans, La.

WILLIAM P. TRENT, M. A.,

Dean of the Department of Arts and Sciences, and Professor of English and History, University of the South, Sewanee, Tenn.

PAUL SHOREY, Ph. D.,

Professor of Greek and Latin Literature, University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill.

WILLIAM T. HARRIS, LL. D.,

United States Commissioner of Education, Bureau of Education, Washington, D. C.

MAURICE FRANCIS EGAN, A. M., LL. D.,

Professor of Literature in the Catholic University of America, Washington, D. C.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

VOL. XII

LIVED PAGE Denis Diderot1713-1784

4689 From 'Rameau's Nephew' Franz von Dingelstedt1814-1881

4704 A Man of Business ('The Amazon') The Watchman (same) Diogenes Laertius200-250 A. D.?

4711 Life of Socrates ('Lives and Sayings of the Philosophers') Examples of Greek Wit and Wisdom: Bias; Plato; Aristippus; Aristotle; Theophrastus; Demetrius; Antisthenes; Diogenes; Cleanthes; Pythagoras Isaac D'Israeli1766-1848

4725 Poets, Philosophers, and Artists Made by Accident ('Curiosities of Literature') Martyrdom of Charles the First ('Commentaries on the Reign of Charles the First') Sydney Dobell1824-1874

4733 Epigram on the Death of Edward Forbes How's My Boy? The Sailor's Return Afloat and Ashore The Soul ('Balder') England (same) America Amy's Song of the Willow ('Balder') Austin Dobson1840-

4741BY ESTHER SINGLETON

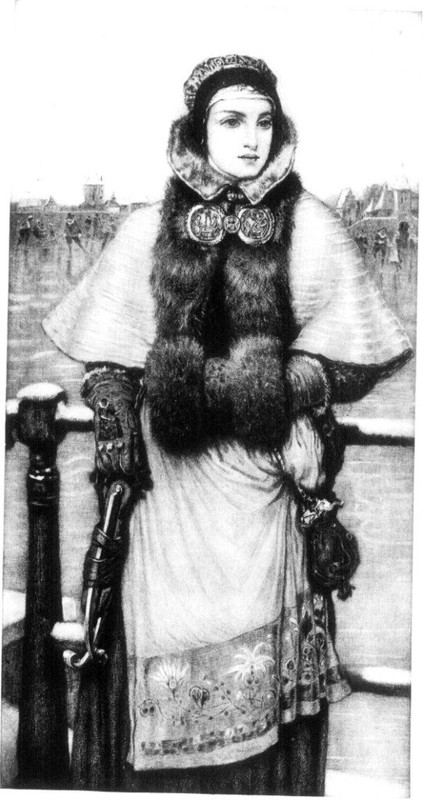

On a Nankin Plate The Old Sedan-Chair Ballad of Prose and Rhyme The Curé's Progress "Good-Night, Babbette" The Ladies of St. James's Dora versus Rose Une Marquise A Ballad to Queen Elizabeth The Princess De Lamballe ('Four Frenchwomen') Mary Mapes Dodge1840?-

4751 The Race ('Hans Brinker') John Donne1573-1631

4771 The Undertaking A Valediction Forbidding Mourning Song Love's Growth Song Feodor Mikhailovitch Dostoévsky1821-1881

4779BY ISABEL F. HAPGOOD

From 'Poor People': Letter from Varvara Debrosyeloff to Makar Dyevushkin; Letter from Makar Dyevushkin to Varvara Alexievna Dobrosyeloff The Bible Reading ('Crime and Punishment') Edward Dowden1843-

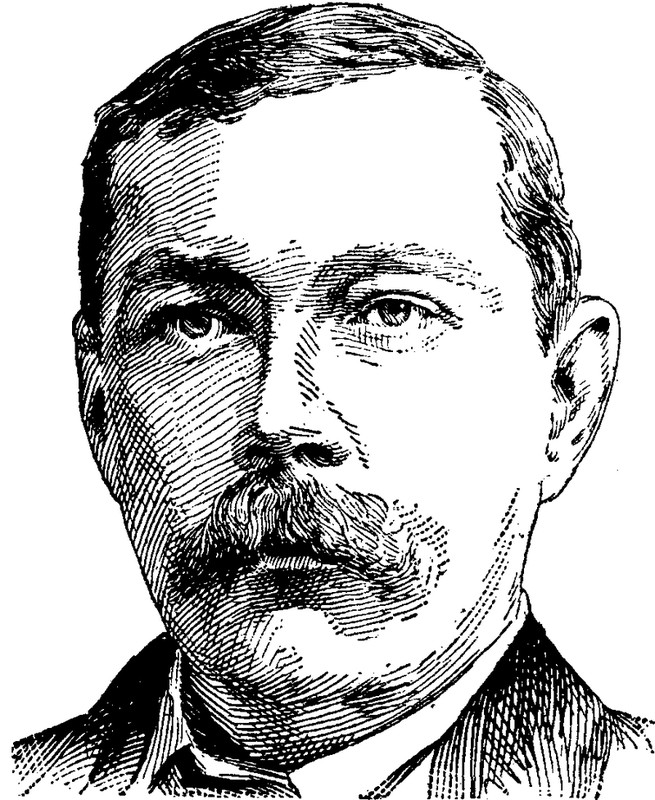

4806 The Humor of Shakespeare ('Shakespeare; a Critical Study of His Mind and Art') Shakespeare's Portraiture of Women ('Transcripts and Studies') The Interpretation of Literature (same) A. Conan Doyle1859-

4815 The Red-Headed League ('The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes') Bowmen's Song ('The White Company') Holger Drachmann1846-

4840 The Skipper and His Ship ('Paul and Virginia of a Northern Zone') The Prince's Song ('Once Upon a Time') Joseph Rodman Drake1795-1820

4851 A Winter's Tale ('The Croakers') The Culprit Fay The American Flag John William Draper1811-1882

4865 The Vedas and Their Theology ('The Intellectual Development of Europe') Primitive Beliefs Dismissed by Scientific Knowledge (same) The Koran (same) Michael Drayton1563-1631

4877 Sonnet The Ballad of Agincourt Queen Mab's Excursion ('Nymphidia, the Court of Faery') Gustave Droz1832-1895

4885 How the Baby Was Saved ('The Seamstress's Story') A Family New-Year's ('Monsieur, Madame, and Bébé') Their Last Excursion ('Making an Omelette') Henry Drummond1851-

4897 The Country and Its People ('Tropical Africa') The East-African Lake Country (same) White Ants (same) William Drummond of Hawthornden1585-1649

4913 Sextain Madrigal Reason and Feeling Degeneracy of the World Briefness of Life The Universe On Death ('Cypress Grove') John Dryden1631-1700

4919BY THOMAS R. LOUNSBURY

From 'The Hind and the Panther' To My Dear Friend Mr. Congreve Ode to the Pious Memory of Mrs. Anne Killigrew A Song Lines Printed under Milton's Portrait Alexander's Feast; or, The Power of Music Achitophel ('Absalom and Achitophel') Maxime Du Camp1822-

4951 Street Scene during the Commune ('The Convulsions of Paris') Alexandre Dumas, Senior1802-1870

4957BY ANDREW LANG

The Cure for Dormice that Eat Peaches ('The Count of Monte Cristo') The Shoulder of Athos, the Belt of Porthos, and the Handkerchief of Aramis ('The Three Musketeers') Defense of the Bastion St.-Gervais (same) Consultation of the Musketeers (same) The Man in the Iron Mask ('The Viscount of Bragelonne') A Trick is Played on Henry III. by Aid of Chicot ('The Lady of Monsoreau') Alexandre Dumas, Junior1824-1895

5001BY FRANCISQUE SARCEY

The Playwright Is Born—and Made (Preface to 'The Prodigal Father') An Armed Truce ('A Friend to the Sex') Two Views of Money ('The Money Question') M. De Remonin's Philosophy of Marriage ('L'Étrangére') Reforming a Father ('The Prodigal Father') Mr. and Mrs. Clarkson ('L'Étrangére') George Du Maurier1834-1896

5041 At the Heart of Bohemia ('Trilby') Christmas in the Latin Quarter (same) "Dreaming True" ('Peter Ibbetson') Barty Josselin at School ('The Martian') William Dunbar1465?-1530?

5064 The Thistle and the Rose From 'The Golden Targe' No Treasure Avails Without Gladness Jean Victor Duruy1811-1894

5069 The National Policy ('History of Rome') Results of the Roman Dominion (same)FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

VOLUME XII

PAGE Javanese Manuscript (Colored Plate)Frontispiece

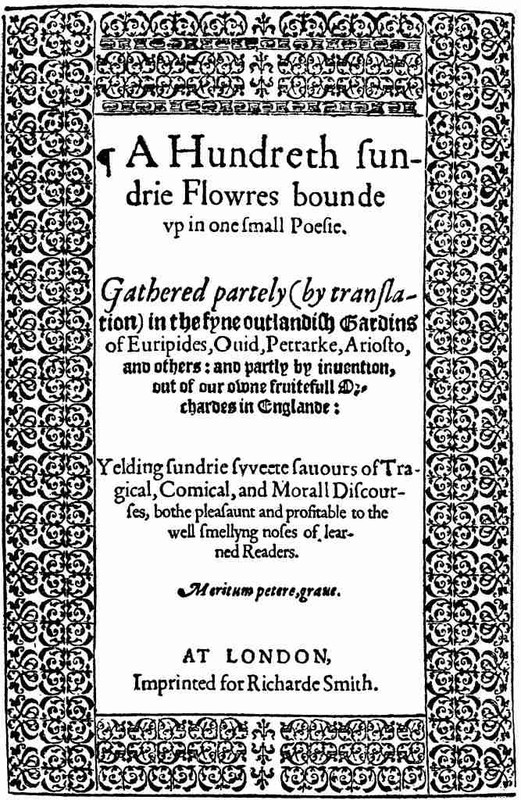

The Alexandrine Manuscript (Fac-simile) xii Old Black-Letter Quarto (Fac-simile) 4726 "Charles I. Going to Execution" (Photogravure) 4730 "The Skater of the Zuyder Zee" (Photogravure) 4758 African Arabic Manuscript (Fac-simile) 4870 John Dryden (Portrait) 4920 Alexandre Dumas (Portrait) 4958 Alexandre Dumas, Fils (Portrait) 5002VIGNETTE PORTRAITS

Denis Diderot Joseph Rodman Drake Franz von Dingelstedt John William Draper Isaac D'Israeli Michael Drayton Austin Dobson Gustav Droz Mary Mapes Dodge Henry Drummond John Donne William Drummond Feodor Dostoévsky Maxime Du Camp A. Conan Doyle George du Maurier Holger Drachmann Jean Victor DuruyFrom the tragic-est novels at Mudie's— At least on a practical plan— To the tales of mere Hodges and Judys, One love is enough for a man. But no case that I ever yet met is Like mine: I am equally fond Of Rose, who a charming brunette is, And Dora, a blonde.

Each rivals the other in powers— Each waltzes, each warbles, each paints— Miss Rose, chiefly tumble-down towers; Miss Do., perpendicular saints. In short, to distinguish is folly; 'Twixt the pair I am come to the pass Of Macheath, between Lucy and Polly,— Or Buridan's ass.

If it happens that Rosa I've singled For a soft celebration in rhyme, Then the ringlets of Dora get mingled Somehow with the tune and the time; Or I painfully pen me a sonnet To an eyebrow intended for Do.'s, And behold I am writing upon it The legend, "To Rose."

Or I try to draw Dora (my blotter Is all over scrawled with her head), If I fancy at last that I've got her, It turns to her rival instead; Or I find myself placidly adding To the rapturous tresses of Rose Miss Dora's bud-mouth, and her madding, Ineffable nose.

Was there ever so sad a dilemma? For Rose I would perish (pro tem.); For Dora I'd willingly stem a— (Whatever might offer to stem); But to make the invidious election,— To declare that on either one's side I've a scruple,—a grain,—more affection, I cannot decide.

And as either so hopelessly nice is, My sole and my final resource Is to wait some indefinite crisis,— Some feat of molecular force, To solve me this riddle conducive By no means to peace or repose, Since the issue can scarce be inclusive Of Dora and Rose.

THE BRIEFNESS OF LIFE

At the outset of his career he found himself received with consideration by the men whose acquaintance he most desired. Following the fashion of the day, and inspired by the books of anecdotes so successfully published by his friend Douce, D'Israeli in 1791 produced anonymously a small volume entitled 'Curiosities of Literature,' the copyright of which he magnanimously presented to his publisher. The extraordinary success of this book can be accounted for only by the curious taste of the time, which still reflected the more unworthy traditions of the Addisonian era. It was an age of clubs and tea-tables, of society scandal-mongering and fireside gossip; and the reading public welcomed a contribution whose refined dilettantism so well matched its own. The mysteries of Eleusis and the origin of wigs received the same grave attention. This popularity induced D'Israeli to buy back the copyright at a generous valuation; he enlarged the work to five volumes, which passed through twelve in his own lifetime, and still serves to illustrate a curious literary phase.

At a dinner given by Sir William Cecil during the plague in 1563, at his apartments at Windsor, where the Queen had taken refuge, a number of ingenious men were invited. Secretary Cecil communicated the news of the morning, that several scholars at Eton had run away on account of their master's severity, which he condemned as a great error in the education of youth. Sir William Petre maintained the contrary; severe in his own temper, he pleaded warmly in defense of hard flogging. Dr. Wootton, in softer tones, sided with the Secretary. Sir John Mason, adopting no side, bantered both. Mr. Haddon seconded the hard-hearted Sir William Petre, and adduced as an evidence that the best schoolmaster then in England was the hardest flogger. Then was it that Roger Ascham indignantly exclaimed that if such a master had an able scholar it was owing to the boy's genius and not the preceptor's rod. Secretary Cecil and others were pleased with Ascham's notions. Sir Richard Sackville was silent; but when Ascham after dinner went to the Queen to read one of the orations of Demosthenes, he took him aside, and frankly told him that though he had taken no part in the debate he would not have been absent from that conversation for a great deal; that he knew to his cost the truth Ascham had supported, for it was the perpetual flogging of such a schoolmaster that had given him an unconquerable aversion to study. And as he wished to remedy this defect in his own children, he earnestly exhorted Ascham to write his observations on so interesting a topic. Such was the circumstance which produced the admirable treatise of Roger Ascham.

"This is not only a tale of vivid description, interesting and instructive; it is a romance. There are adventures, startling and surprising, there are mysteries of buried gold, there are the machinations of the wicked, there is the heroism of the good, and the gay humor of happy souls. More than these, there is love—that sentiment which glides into a good story as naturally as into a human life; and whether the story be for old or young, this element gives it an ever-welcome charm. Strange fortune and good fortune come to Hans and to Gretel, and to many other deserving characters in the tale, but there is nothing selfish about these heroes and heroines. As soon as a new generation of young people grows up to be old enough to enjoy this perennial story, all these characters return to the days of their youth, and are ready to act their parts again to the very end, and to feel in their own souls, as everybody else feels, that their story is just as new and interesting as when it was first told."

Thus extending our view from the earth to the solar system, from the solar system to the expanse of the group of stars to which we belong, we behold a series of gigantic nebular creations rising up one after another, and forming greater and greater colonies of worlds. No numbers can express them, for they make the firmament a haze of stars. Uniformity, even though it be the uniformity of magnificence, tires at last, and we abandon the survey; for our eyes can only behold a boundless prospect, and conscience tells us our own unspeakable insignificance.

Dryden's first published literary effort appeared in a little volume made up of thirty-three elegies, by various authors, on the death of a youth of great promise who had been educated at Westminster. This was Lord Hastings, the eldest son of the Earl of Huntingdon. He had died of the small-pox. Dryden's contribution was written in 1649, and consisted of but little over a hundred lines. No one expects great verse from a boy of eighteen; but the most extravagant anticipations of sorry performance will fail to come up to the reality of the wretchedness which was here attained. It was in words like these that the future laureate bewailed the death of the young nobleman and depicted the disease of which he died:—

It is notorious that Dumas was at the head of a "Company" like that which Scott laughingly proposed to form "for writing and publishing the class of books called Waverley Novels." In legal phrase, Dumas "deviled" his work; he had assistants, "researchers," collaborators. He would briefly sketch a plot, indicate the authorities to be consulted, hand his notes to Maquet or Fiorentino, receive their draught, and expand that into a romance. Work thus executed cannot be equal to itself. Many books signed by Dumas may be neglected without loss. Even to his best works, one or other of his assistants was apt to assert a claim. The answer is convincing. Not one of these ingenious men ever produced, by himself, anything that could be mistaken for the work of the master. All his good things have the same stamp and the same spirit, which we find nowhere else. Again, nobody contests his authorship of his own 'Memoirs,' or of his book about his dogs, birds, and other beasts—'The Story of My Pets.' Now, the merit of these productions is, in kind, identical with many of the merits of his best novels. There is the same good-humor, gayety, and fullness of life. We may therefore read Dumas's central romances without much fear of being grateful to the wrong person. Against the modern theory that the Iliad and Odyssey are the work of many hands in many ages, we can urge that these supposed "hands" never did anything nearly so good for themselves; and the same argument applies in the case of Alexandre Dumas.

Such was indeed the young man's intention. His first work was a one-act play in verse, 'The Queen's Jewel,' which no one, assuredly, would mention to-day but for his signature. The date was 1845, and the author was then twenty-one. Other works by him were published at various times in the Journal des Demoiselles.

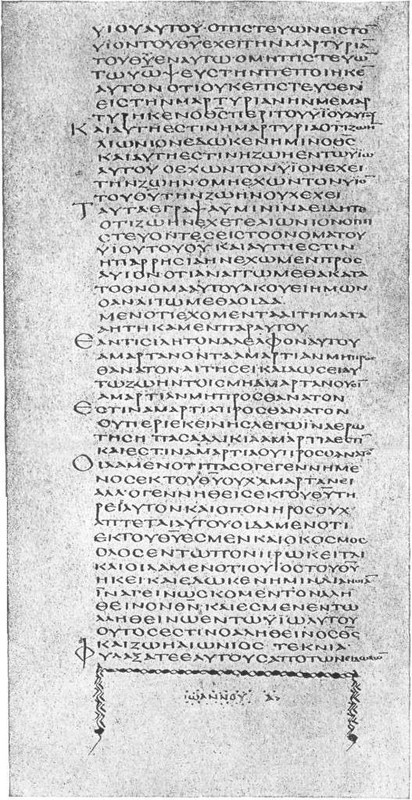

CODEX ALEXANDRINUS. Fifth Century. British Museum.

The Alexandrine Manuscript of the Christian Scriptures is almost complete in both Testaments, the Septuagint version of the Old and the original Greek of the New. It consists of 773 sheets, 12¾ by 10¾ inches, of very thin gray goatskin vellum, written on both sides in two columns of faint but clear characters. It was made in the early part of the fifth century, under the supervision of Thecla, a noble Christian lady of Alexandria, in the fifth century. It was brought from Alexandria to Constantinople by Cyril Lucar, Patriarch of Constantinople, who in 1624 gave it into the charge of the English Ambassador for presentation to King James I.; but owing to James' death before the presentation could be made, it was presented instead to Charles I. It remained in the possession of the English sovereigns until the Royal Library was presented to the nation by George II. in 1753. With the exception of the greater part of Matthew to Chapter xxv., two leaves of John, and three of Second Corinthians, it contains the whole Greek Bible, including the two Epistles of Clement of Rome, which in early times ranked among the inspired books. Its table of contents shows that it once included also the "Psalms of Solomon," though, from their position and title in the index, it is evident that they were regarded as standing apart from the other books. The Museum has bound the leaves of this precious manuscript in four volumes, and has had photographic copies made of each page for the use of students. The accompanying reproduction is from the last chapter of the First Epistle of John, from "His Son," in verse 9, to the end.

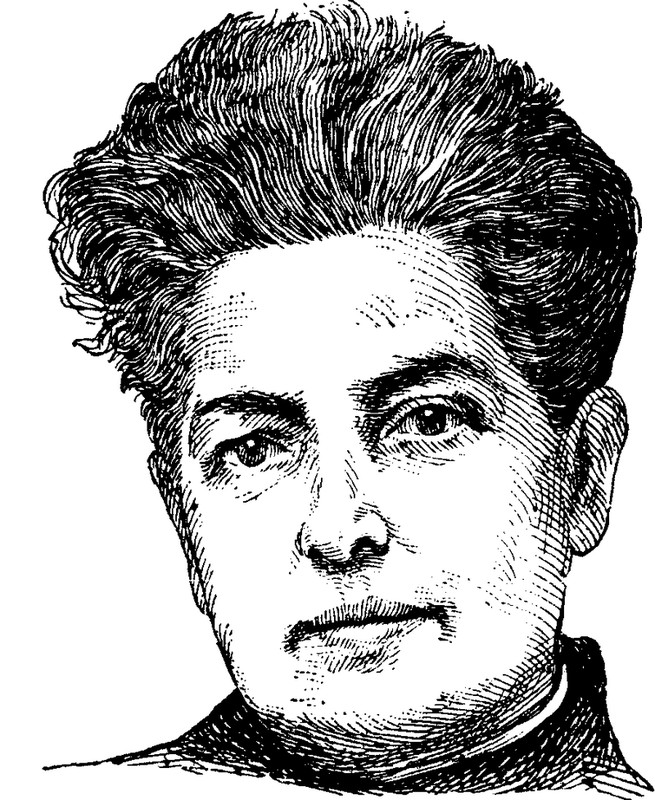

DENIS DIDEROT

(1713-1784)

mong the French Encyclopædists of the eighteenth century Denis Diderot holds the place of leader. There were intellects of broader scope and of much surer balance in that famous group, but none of such versatility, brilliancy, and outbursting force. To his associates he was a marvel and an inspiration.

Denis Diderot

He was born in October 1713, in Langres, Haute-Marne, France; and died in Paris July 31st, 1784. After a classical education in Jesuit schools, he utterly disgusted his father by turning to the Bohemian life of a littérateur in Paris. Although very poor, he married at the age of thirty. The whole story of his married life—the common Parisian story in those days—reflects no credit on him; though his liaison with Mademoiselle Voland presents the aspects of a friendship abiding through life. Poverty spurred him to exertion. Four days of work in 1746 are said to have produced 'Pensées Philosophiques' (Philosophic Thoughts). This book, with a little essay following it, 'Interprétation de la Nature,' was his first open attack on revealed religion. Its argument, though only negative, and keeping within the bounds of theism, foretokened a class of utterances which were frequent in Diderot's later years, and whose assurance of his materialistic atheism would be complete had they not been too exclamatory for settled conviction. He contents himself with glorifying the passions, to the annulling of all ethical standards. On this point at least his convictions were stable, for long afterward he writes thus to Mademoiselle Voland:—"The man of mediocre passion lives and dies like the brute.... If we were bound to choose between Racine, a bad husband, a bad father, a false friend, and a sublime poet, and Racine, good father, good husband, good friend, and dull worthy man, I hold to the first. Of Racine the bad man, what remains? Nothing. Of Racine the man of genius? The work is eternal."

About 1747 he produced an allegory, 'Promenade du Sceptique.' This French 'Pilgrim's Progress' scoffs at the Church of Rome for denying pleasure, then decries the pleasures of the world, and ends by asserting the hopeless uncertainty of the philosophy which both scoffs at the Church and decries worldly pleasure. At this period he was evidently inclined to an irregular attack on the only forms of Christianity familiar to him, asceticism and pietism.

In 1749 Diderot first showed himself a thinker of original power, in his Letter on the Blind. This work, 'Lettre sur les Avengles à l'Usage de Ceux qui Voient' (Letter on the Blind for the Use of Those who See) opened the eyes of the public to Diderot's peculiar genius, and the eyes of the authorities to the menace in his principles. The result was his imprisonment, and from that the spread of his views. His offense was, that through his ingenious supposition of the mind deprived of its use of one or more of the bodily senses, he had shown the relativity of all man's conceptions, and had thence deduced the relativity, the lack of absoluteness, of all man's ethical standards—thus invalidating the foundations of civil and social order. The broad assertion that Diderot and his philosophic group caused the French Revolution has only this basis, that these men were among the omens of its advance, feeling its stir afar but not recognizing the coming earthquake. Yet it may be conceded that Diderot anticipated things great and strange; for his mind, although neither precise nor capable of sustained and systematic thought, was amazingly original in conception and powerful in grasp. The mist, blank to his brethren, seems to have wreathed itself into wonderful shapes to his eye; he was the seer whose wild enthusiasm caught the oracles from an inner shrine. A predictive power appears in his Letter on the Blind, where he imagines the blind taught to read by touch; and nineteenth-century hypotheses gleam dimly in his random guess at variability in organisms, and at survival of those best adapted to their environment.

Diderot's monumental work, 'L'Encyclopédie,' dates from the middle of the century. It was his own vast enlargement of Ephraim Chambers's Cyclopædia of 1727, of which a bookseller had demanded a revision in French. D'Alembert was secured as his colleague, and in 1751 the first volume appeared. The list of contributors includes most of the great contemporary names in French literature. From these, Diderot and D'Alembert gathered the inner group known as the French Encyclopædists, to whose writings has been ascribed a general tendency to destroy religion and to reconstitute society. The authorities interfered repeatedly, with threats and prohibitions of the publication; but the science of government included the science of connivance for an adequate consideration, and the great work went forward. Its danger lurked in its principles; for Diderot dealt but little in the cheap flattery which the modern demagogue addresses to the populace. D'Alembert, wearied by ten years of persecution, retired in 1759, leaving the indefatigable Diderot to struggle alone through seven years, composing and revising hundreds of articles, correcting proofs, supervising the unrivaled illustrations of the mechanic arts, while quieting the opposition of the authorities.

The Encyclopædia under Diderot followed no one philosophic path. Indeed, there are no signs that he ever gave any consideration to either the intellectual or the ethical force of consistency. His writing indicates his utter carelessness both as to the direction and as to the pace of his thought. He had an abiding conviction that Christianity was partly delusion and largely priestcraft, and was maintained chiefly for upholding iniquitous privilege. His antagonism was developed primarily from his emotions and sympathies rather than from his intellect; hence it sometimes swerved, drawing perilously near to formal orthodoxy. Moreover, this vivacious philosopher sometimes rambled into practical advice, and easily effervesced into fervid moralizings of the sentimental and almost tearful sort. His immense natural capacity for sentiment appears in his own account of his meeting with Grimm after a few months' absence. His sentimentalism, however, had its remarkable counterpoise in a most practical tendency of mind. In the Encyclopædia the interests of agriculture and of all branches of manufacture were treated with great fullness; and the reform of feudal abuses lingering in the laws of France was vigorously urged in a style more practical than cyclopædic.

Diderot gave much attention to the drama, and his 'Paradoxe sur le Comédien' (Paradox on the Actor) is a valuable discussion. He is the father of the modern domestic drama. His influence upon the dramatic literature of Germany was direct and immediate; it appeared in the plays of Lessing and Schiller, and much of Lessing's criticism was inspired by Diderot. His 'Père de Famille' (Family-Father) and 'Le Fils Naturel' (The Natural Son) marked the beginning of a new era in the history of the stage, in the midst of which we are now living. Breaking with the old traditions, Diderot abandoned the lofty themes of classic tragedy and portrayed the life of the bourgeoisie. The influence of England, frequently manifest in the work of the Encyclopædists, is evident also here. Richardson was then the chief force in fiction, and the sentimental element so characteristic in him reappears in the dramas of Diderot.

Goethe was strongly attracted by the genius of Diderot, and thought it worth his while not only to translate but to supply with a long and luminous commentary the latter's 'Essay on Painting.' It was by a singular trick of fortune, too, that one of Diderot's most powerful works should first have appeared in German garb, and not in the original French until after the author's death. A manuscript copy of the book chanced to fall into the hands of Goethe, who so greatly admired it that he at once translated, annotated, and published it. This was the famous dialogue 'Le Neveu de Rameau' (Rameau's Nephew), a work which only Diderot's peculiar genius could have produced. Depicting the typical parasite, shameless, quick-witted for every species of villainy, at home in every possible meanness, the dialogue is a probably unequaled compound of satire, high æsthetics, gleaming humor, sentimental moralizing, fine musical criticism, and scientific character analysis, with passages of brutal indecency.

Among literary critics of painting, Diderot has his place in the highest rank. His nine 'Salons'—criticisms which in his good-nature he wrote for the use of his friend Grimm, on the annual exhibitions in the Paris Salon from 1759 onward—have never been surpassed among non-technical criticisms for brilliancy, freshness, and philosophic suggestiveness. They reveal the man's elemental strength; which was not in his knowledge, for he was without technical training in art and had seen scarcely any of the world's masterpieces, but in his sensuously sympathetic nature, which gave him quickness of insight and delicacy in interpretation.

He had the faculty of making and keeping friends, being unaffected, genial, amiable, enthusiastically generous and helpful to his friends, and without vindictiveness to his foes. He needed these qualities to counteract his almost utter lack of conscientiousness, his gush of sentiment, his unregulated morals, his undisciplined genius, his unbalanced thought. His style of writing, often vivid and strong, is as often awkward and dull, and is frequently lacking in finish. As a philosophic author and thinker his voluminous work is of little enduring worth, for though plentiful in original power it totally lacks organic unity; his thought rambles carelessly, his method is confused. It has been said of him that he was a master who produced no masterpiece. But as a talker, a converser, all witnesses testify that he was wondrously inspiring and suggestive, speaking sometimes as from mysterious heights of vision or out of unsearchable deeps of thought.

FROM 'RAMEAU'S NEPHEW'

Be the weather fair or foul, it is my custom in any case at five o'clock in the afternoon to stroll in the Palais Royal. I am always to be seen alone and meditative, on the bench D'Argenson. I hold converse with myself on politics or love, on taste or philosophy, and yield up my soul entirely to its own frivolity. It may follow the first idea that presents itself, be the idea wise or foolish. In the Allée de Foi one sees our young rakes following upon the heels of some courtesan who passes on with shameless mien, laughing face, animated glance, and a pug nose; but they soon leave her to follow another, teasing them all, joining none of them. My thoughts are my courtesans.

When it is really too cold or rainy, I take refuge in the Café de la Régence and amuse myself by watching the chess-players. Paris is the place of the world and the Café de la Régence the place of Paris where the best chess is played. There one witnesses the most carefully calculated moves; there one hears the most vulgar conversation; for since it is possible to be at once a man of intellect and a great chess-player, like Légal, so also one may be at once a great chess-player and a very silly person, like Foubert or Mayot.

One afternoon I was there, observing much, speaking rarely, and hearing as little as possible, when one of the most singular personages came up to me that ever was produced by this land of ours, where surely God has never caused a dearth of singular characters. He is a combination of high-mindedness and baseness, of sound understanding and folly; in his head the conceptions of honor and dishonor must be strangely tangled, for the good qualities with which nature has endowed him he displays without boastfulness, and the bad qualities without shame. For the rest, he is firmly built, has an extraordinary power of imagination, and possesses an uncommonly strong pair of lungs. Should you ever meet him and succeed in escaping from the charm of his originality, it must be by stopping both ears with your fingers or by precipitate flight. Heavens, what terrible lungs!

And nothing is less like him than he himself. Sometimes he is thin and wasted, like a man in the last stages of consumption; you could count his teeth through his cheeks; you would think he had not tasted food for several days, or had come from La Trappe.

A month later he is fattened and filled out as if he had never left the banquets of the rich or had been fed among the Bernardines. To-day, with soiled linen, torn trousers, clad in rags, and almost barefoot, he passes with bowed head, avoids those whom he meets, till one is tempted to call him and bestow upon him an alms. To-morrow, powdered, well groomed, well dressed, and well shod, he carries his head high, lets himself be seen, and you would take him almost for a respectable man.

So he lives from day to day, sad or merry, according to the circumstances. His first care, when he rises in the morning, is to take thought where he is to dine. After dinner he bethinks himself of some opportunity to procure supper, and with the night come new cares. Sometimes he goes on foot to his little attic, which is his home if the landlady, impatient at long arrears of rent, has not taken the key away from him. Sometimes he goes to one of the taverns in the suburbs, and there, between a bit of bread and a mug of beer, awaits the day. If he lacks the six sous necessary to procure him quarters for the night, which is occasionally the case, he applies to some cabman among his friends or to the coachman of some great lord, and a place on the straw beside the horses is vouchsafed him. In the morning he carries a part of his mattress in his hair. If the season is mild, he spends the whole night strolling back and forth on the Cours or in the Champs Élysées. With the day he appears again in the city, dressed yesterday for to-day and to-day often for the rest of the week.

For such originals I cannot feel much esteem, but there are others who make close acquaintances and even friends of them. Once in the year perhaps they are able to put their spell upon me, when I meet them, because their character is in such strong contrast to that of every-day humanity, and they break the oppressive monotony which our education, our social conventions, our traditional proprieties have produced. When such a man enters a company, he acts like a cake of yeast that raises the whole, and restores to each a part of his natural individuality. He shakes them up, brings things into motion, elicits praise or censure, drives truth into the open, makes upright men recognizable, unmasks the rogues, and there the wise man sits and listens and is enabled to distinguish one class from another.

This particular specimen I had long known; he frequented a house into which his talents had secured him the entrée. These people had an only daughter. He swore to the parents that he would marry their daughter. They only shrugged their shoulders, laughed in his face, and assured him that he was a fool. But I saw the day come when the thing was accomplished. He asked me for some money, which I gave him. He had, I know not how, squirmed his way into a few houses, where a couvert stood always ready for him, but it had been stipulated that he should never speak without the consent of his hosts. So there he sat and ate, filled the while with malice; it was fun to see him under this restraint. The moment he ventured to break the treaty and open his mouth, at the very first word the guests all shouted "O Rameau!" Then his eyes flashed wrathfully, and he fell upon his food again with renewed energy.

You were curious to know the man's name; there it is. He is the nephew of the famous composer who has saved us from the church music of Lulli which we have been chanting for a hundred years, ... and who, having buried the Florentine, will himself be buried by Italian virtuosi; he dimly feels this, and so has become morose and irritable, for no one can be in a worse humor—not even a beautiful woman who in the morning finds a pimple on her nose—than an author who sees himself threatened with the fate of outliving his reputation, as Marivaux and Crébillon fils prove.

Rameau's nephew came up to me. "Ah, my philosopher, do I meet you once again? What are you doing here among the good-for-nothings? Are you wasting your time pushing bits of wood about?"

I—No; but when I have nothing better to do, I take a passing pleasure in watching those who push them about with skill.

He—A rare pleasure, surely. Excepting Légal and Philidor, there is no one here that understands it....

I—You are hard to please. I see that only the best finds favor with you.

He—Yes, in chess, checkers, poetry, oratory, music, and such other trumpery. Of what possible use is mediocrity in these things?

I—I am almost ready to agree with you....

He—You have always shown some interest in me, because I'm a poor devil whom you really despise, but who after all amuses you.

I—That is true.

He—Then let me tell you. (Before beginning, he drew a deep sigh, covered his forehead with both hands, then with calm countenance continued:—) You know I am ignorant, foolish, silly, shameless, rascally, gluttonous.

I—What a panegyric!

He—It is entirely true. Not a word to be abated; no contradiction, I pray you. No one knows me better than I know myself, and I don't tell all.

I—Rather than anger you, I will assent.

He—Now, just think, I lived with people who valued me precisely because all these qualities were mine in a high degree.

I—That is most remarkable. I have hitherto believed that people concealed these qualities even from themselves, or excused them, but always despised them in others.

He—Conceal them? Is that possible? You may be sure that when Palissot is alone and contemplates himself, he tells quite a different story. You may be sure that he and his companion make open confession to each other that they are a pair of arrant rogues. Despise these qualities in others? My people were much more reasonable, and I fared excellently well among them. I was cock of the walk. When absent, I was instantly missed. I was pampered. I was their little Rameau, their good Rameau, the shameless, ignorant, lazy Rameau, the fool, the clown, the gourmand. Each of these epithets was to me a smile, a caress, a slap on the back, a box on the ears, a kick, a dainty morsel thrown upon my plate at dinner, a liberty permitted me after dinner as if it were of no account; for I am of no account. People make of me and do before me and with me whatever they please, and I never give it a thought....

I—You have been giving lessons, I understand, in accompaniment and composition?

He—Yes.

I—And you knew absolutely nothing about it?

He—No, by Heaven; and for that very reason I was a much better teacher than those who imagine they know something about it. At all events, I didn't spoil the taste nor ruin the hands of my young pupils. If when they left me they went to a competent master, they had nothing to unlearn, for they had learned nothing, and that was just so much time and money saved.

I—But how did you do it?

He—The way they all do it. I came, threw myself into a chair:—"How bad the weather is! How tired the pavement makes one!" Then some scraps of town gossip:... "At the last Amateur Concert there was an Italian woman who sang like an angel.... Poor Dumênil doesn't know what to say or do," etc., etc. ... "Come, mademoiselle, where is your music-book?" And as mademoiselle displays no great haste, searches every nook and corner for the book, which she has mislaid, and finally calls the maid to help her, I continue:—"Little Clairon is an enigma. There is talk of a perfectly absurd marriage of—what is her name?"—"Nonsense, Rameau, it isn't possible."—"They say the affair is all settled." ... "There is a rumor that Voltaire is dead,"—"All the better."—"Why all the better?"—"Then he is sure to treat us to some droll skit. That's a way he has, a fortnight before his death." What more should I say? I told a few scandals about the families in the houses where I am received, for we are all great scandal-mongers. In short, I played the fool; they listened and laughed, and exclaimed, "He is really too droll, isn't he?" Meanwhile the music-book had been found under a chair, where a little dog or a little cat had worried it, chewed it, and torn it. Then the pretty child sat down at the piano and began to make a frightful noise upon it. I went up to her, secretly making a sign of approbation to her mother. "Well, now, that isn't so bad," said the mother; "one needs only to make up one's mind to a thing; but the trouble is, one will not make up one's mind; one would rather kill time by chattering, trifling, running about, and God knows what. Scarcely do you turn your back but the book is closed, and not until you are at her side again is it opened. Besides, I have never heard you reprimand her." In the mean time, since something had to be done, I took her hands and placed them differently. I pretended to lose my patience; I shouted,—"Sol, sol, sol, mademoiselle, it's a sol." The mother: "Mademoiselle, have you no ears? I'm not at the piano, I'm not looking at your notes, but my own feeling tells me that it ought to be a sol. You give the gentleman infinite trouble. You remember nothing, and make no progress." To break the force of this reproof a little, I tossed my head and said: "Pardon me, madame, pardon me. It would be better if mademoiselle would only practice a little, but after all it is not so bad."—"In your place I would keep her a whole year at one piece."—"Rest assured, I shall not let her off until she has mastered every difficulty; and that will not take so long, perhaps, as mademoiselle thinks."—"Monsieur Rameau, you flatter her; you are too good." And that is the only thing they would remember of the whole lesson, and would upon occasion repeat to me. So the lesson came to an end. My pupil handed me the fee, with a graceful gesture and a courtesy which her dancing-master had taught her. I put the money into my pocket, and the mother said, "That's very nice, mademoiselle. If Favillier were here, he would praise you." For appearance's sake I chattered for a minute or two more; then I vanished; and that is what they called in those days a lesson in accompaniment.

I—And is the case different now?

He—Heavens! I should think so. I come in, I am serious, throw my muff aside, open the piano, try the keys, show signs of great impatience, and if I am kept a moment waiting I shout as if my purse had been stolen. In an hour I must be there or there; in two hours with the Duchess So-and-so; at noon I must go to the fair Marquise; and then there is to be a concert at Baron de Bagge's, Rue Neuve des Petits Champs.

I—And meanwhile no one expects you at all.

He—Certainly not.... And precisely because I can further my fortune through vices which come natural to me, which I acquired without labor and practice without effort, which are in harmony with the customs of my countrymen, which are quite to the taste of my patrons, and better adapted to their special needs than inconvenient virtues would be, which from morning to night would be standing accusations against them, it would be strange indeed if I should torture myself like one of the damned to twist and turn and make of myself something which I am not, and hide myself beneath a character foreign to me, and assume the most estimable qualities, whose worth I will not dispute, but which I could acquire and live up to only by great exertions, and which after all would lead to nothing,—perhaps to worse than nothing. Moreover, ought a beggar like me, who lives upon the wealthy, constantly to hold up to his patrons a mirror of good conduct? People praise virtue but hate it; they fly from it, let it freeze; and in this world a man has to keep his feet warm. Besides, I should always be in the sourest humor: for why is it that the pious and the devotional are so hard, so repellent, so unsociable? It is because they have imposed upon themselves a task contrary to their nature. They suffer, and when a man suffers he makes others suffer. Now, that is no affair of mine or of my patrons'. I must be in good spirits, easy, affable, full of sallies, drollery, and folly. Virtue demands reverence, and reverence is inconvenient; virtue challenges admiration, and admiration is not entertaining. I have to do with people whose time hangs heavy on their hands; they want to laugh. Now consider the folly: the ludicrous makes people laugh, and I therefore must be a fool; I must be amusing, and if nature had not made me so, then by hook or by crook I should have made myself seem so. Fortunately I have no need to play the hypocrite. There are hypocrites enough of all colors without me, and not counting those who deceive themselves.... Should it ever occur to friend Rameau to play Cato, to despise fortune, women, good living, idleness, what would he be? A hypocrite. Let Rameau remain what he is, a happy robber among wealthy robbers, and a man without either real or boasted virtue. In short, your idea of happiness, the happiness of a few enthusiastic dreamers like you, has no charm for me....

I—He earns his bread dearly, who in order to live must assail virtue and knowledge.

He—I have already told you that we are of no consequence. We slander all men and grieve none.

[The dialogue reverts to music.]

I—Every imitation has its original in nature. What is the musician's model when he breaks into song?

He—Why do you not grasp the subject higher up? What is song?

I—That, I confess, is a question beyond my powers. That's the way with us all. The memory is stored with words only, which we think we understand because we often use them and even apply them correctly, but in the mind we have only indefinite conceptions. When I use the word "song," I have no more definite idea of it than you and the majority of your kind have when you say reputation, disgrace, honor, vice, virtue, shame, propriety, mortification, ridicule.

He—Song is an imitation in tones, produced either by the voice or by instruments, of a scale invented by art, or if you will, established by nature; an imitation of physical sounds or passionate utterances; and you see, with proper alterations this definition could be made to fit painting, oratory, sculpture, and poetry. Now to come to your question, What is the model of the musician or of song? It is the declamation, when the model is alive or sensate; it is the tone, when the model is insensate. The declamation must be regarded as a line, and the music as another line which twines about it. The stronger and the more genuine is this declamation, this model of song, the more numerous the points at which the accompanying music intersects it, the more beautiful will it be. And this our younger composers have clearly perceived. When one hears "Je suis un pauvre diable," one feels that it is a miser's complaint. If he didn't sing, he would address the earth in the very same tones when he intrusts to its keeping his gold: "O terre, reçois mon trésor." ... In such works with the greatest variety of characters, there is a convincing truth of declamation that is unsurpassed. I tell you, go, go, and hear the aria where the young man who feels that he is dying, cries out, "Mon cœur s'en va." Listen to the air, listen to the accompaniment, and then tell me what difference there is between the true tones of a dying man and the handling of this music. You will see that the line of the melody exactly coincides with the line of declamation. I say nothing of the time, which is one of the conditions of song; I confine myself to the expression, and there is nothing truer than the statement which I have somewhere read, "Musices seminarium accentus,"—the accent is the seed-plot of the melody. And for that reason, consider how difficult and important a matter it is to be able to write a good recitative. There is no beautiful aria out of which a beautiful recitative could not be made; no beautiful recitative out of which a clever man could not produce a beautiful aria. I will not assert that one who recites well will also be able to sing well, but I should be much surprised if a good singer could not recite well. And you may believe all that I tell you now, for it is true.

(And then he walked up and down and began to hum a few arias from the "Île des Fons," etc., exclaiming from time to time, with upturned eyes and hands upraised:—) "Isn't that beautiful, great heavens! isn't that beautiful? Is it possible to have a pair of ears on one's head and question its beauty?" Then as his enthusiasm rose he sang quite softly, then more loudly as he became more impassioned, then with gestures, grimaces, contortions of body. "Well," said I, "he is losing his mind, and I may expect a new scene." And in fact, all at once he burst out singing.... He passed from one aria to another, fully thirty of them,—Italian, French, tragic, comic, of every sort. Now with a deep bass he descended into hell; then, contracting his throat, he split the upper air with a falsetto, and in gait, mien, and action he imitated the different singers, by turns raving, commanding, mollified, scoffing. There was a little girl that wept, and he hit off all her pretty little ways. Then he was a priest, a king, a tyrant; he threatened, commanded, stormed; then he was a slave and submissive. He despaired, he grew tender, he lamented, he laughed, always in the tone, the time, the sense of the words, of the character, of the situation.

All the chess-players had left their boards and were gathered around him; the windows of the café were crowded with passers-by, attracted by the noise. There was laughter enough to bring down the ceiling. He noticed nothing, but went on in such a rapt state of mind, in an enthusiasm so close to madness, that I was uncertain whether he would recover, or if he would be thrown into a cab and taken straight to the mad-house; the while he sang the Lamentations of Jomelli.

With precision, fidelity, and incredible warmth, he rendered one of the finest passages, the superb obligato recitative in which the prophet paints the destruction of Jerusalem; he wept himself, and the eyes of the listeners were moist. More could not be desired in delicacy of vocalization, nor in the expression of overwhelming grief. He dwelt especially on those parts in which the great composer has shown his greatness most clearly. When he was not singing, he took the part of the instruments; these he quickly dropped again, to return to the vocal part, weaving one into the other so perfectly that the connection, the unity of the whole, was preserved. He took possession of our souls and held them in the strangest suspense I have ever experienced. Did I admire him? Yes, I admired him. Was I moved and melted? I was moved and melted, and yet something of the ludicrous mingled itself with these feelings and modified their nature.

But you would have burst out laughing at the way he imitated the different instruments. With a rough muffled tone and puffed-out cheeks he represented horns and bassoon; for the oboe he assumed a rasping nasal tone; with incredible rapidity he made his voice run over the string instruments, whose tones he endeavored to reproduce with the greatest accuracy; the flute passages he whistled; he rumbled out the sounds of the German flute; he shouted and sang with the gestures of a madman, and so alone and unaided he impersonated the entire ballet corps, the singers, the whole orchestra,—in short, a complete performance,—dividing himself into twenty different characters, running, stopping, with the mien of one entranced, with glittering eyes and foaming mouth.... He was quite beside himself. Exhausted by his exertions, like a man awakening from a deep sleep or emerging from a long period of abstraction, he remained motionless, stupefied, astonished. He looked about him in bewilderment, like one trying to recognize the place in which he finds himself. He awaited the return of his strength, of his consciousness; he dried his face mechanically. Like one who upon awaking finds his bed surrounded by groups of people, in complete oblivion and profound unconsciousness of what he had been doing, he cried, "Well, gentlemen, what's the matter? What are you laughing at? What are you wondering about? What's the matter?"

I—My dear Rameau, let us talk again of music. Tell me how it comes that with the facility you display for appreciating the finest passages of the great masters, for retaining them in your memory, and for rendering them to the delight of others with all the enthusiasm with which the music inspires you,—how comes it that you have produced nothing of value yourself?

(Instead of answering me, he tossed his head, and raising his finger towards heaven, cried:—)

The stars, the stars! When nature made Leo, Vinci, Pergolese, Duni, she wore a smile; her face was solemn and commanding when she created my dear uncle Rameau, who for ten years has been called the great Rameau, and who will soon be named no more. But when she scraped his nephew together, she made a face and a face and a face.—(And as he spoke he made grimaces, one of contempt, one of irony, one of scorn. He went through the motions of kneading dough, and smiled at the ludicrous forms he gave it. Then he threw the strange pagoda from him.) So she made me and threw me down among other pagodas, some with portly well-filled paunches, short necks, protruding goggle eyes, and an apoplectic appearance; others with lank and crooked necks and emaciated forms, with animated eyes and hawks' noses. These all felt like laughing themselves to death when they saw me, and when I saw them I set my arms akimbo and felt like laughing myself to death, for fools and clowns take pleasure in one another; seek one another out, attract one another. Had I not found upon my arrival in this world the proverb ready-made, that the money of fools is the inheritance of the clever, the world would have owed it to me. I felt that nature had put my inheritance into the purse of the pagodas, and I tried in a thousand ways to recover it.

I—I know these ways. You have told me of them. I have admired them. But with so many capabilities, why do you not try to accomplish something great?

He—That is exactly what a man of the world said to the Abbé Le Blanc. The abbé replied:—"The Marquise de Pompadour takes me in hand and brings me to the door of the Academy; then she withdraws her hand; I fall and break both legs."—"You ought to pull yourself together," rejoined the man of the world, "and break the door in with your head."—"I have just tried that," answered the abbé, "and do you know what I got for it? A bump on the head." ... (Then he drank a swallow from what remained in the bottle and turned to his neighbor.) Sir, I beg you for a pinch of snuff. That's a fine snuff-box you have there. You are a musician? No! All the better for you. They are a lot of poor deplorable wretches. Fate made me one of them, me! Meanwhile at Montmartre there is a mill, and in the mill there is perhaps a miller or a miller's lad, who will never hear anything but the roaring of the mill, and who might have composed the most beautiful of songs. Rameau, get you to the mill, to the mill; it's there you belong . . . But it is half-past five. I hear the vesper bell which summons me too. Farewell. It's true, is it not, philosopher, I am always the same Rameau?

I—Yes, indeed. Unfortunately.

He—Let me enjoy my misfortune forty years longer. He laughs best who laughs last.

Translated for 'A Library of the World's Best Literature.'

FRANZ VON DINGELSTEDT

(1814-1881)

ranz von Dingelstedt was born at Halsdorf, Hessen, Germany, June 30th, 1814. He attained eminence as a poet and dramatist, but his best powers were devoted to his principal calling as theatre director.

His boyhood's education was received at Rinteln. At the University of Marburg he applied himself to theology and philology, but more especially to modern languages and literature. After leaving the university he became instructor at Ricklingen, near Hanover. He was characterized, even as a young man, by his political freedom and independence of thought; and at Cassel, where in 1836 he was teacher in the Lyceum, he was on this account looked upon so much askance that it was found expedient to transfer him to the gymnasium at Fulda (1838). He resigned this position, however, in order to devote himself to writing. A collection of his poems appeared in 1838-45, and of these, 'Lieder eines Kosmopolitischen Nachtwächters' (Songs of a Cosmopolitan Night-Watchman: 1841) may be said to have produced a genuine agitation. These were not only important as literature, but as political promulgations, boldly embodying the radical sentiments of freethinking Germany.

Dingelstedt

In 1841 he went to Augsburg, connected himself with the Allgemeine Zeitung, and traveled as newspaper correspondent in France, Holland, Belgium, and England. 'Das Wanderbuch' (The Wander-Book), and 'Jusqu' à la Mer—Erinnerungen aus Holland' (As Far as the Sea—Remembrances of Holland: 1847), were the fruits of these journeys. He had in contemplation a voyage to the Orient, and preparatory to this he settled for a short time in Vienna; but the journey was not undertaken, for just at this time he was appointed librarian of the Royal Library of Stuttgart, and reader to the king, with the title of Court Councilor. Here in 1844 he married the celebrated singer Jenny Lutzer. He returned to Vienna, where in 1850 his drama 'Das Haus der Barneveldt' (The House of the Barneveldts) was produced with such brilliant success that he was thereupon appointed stage manager of the National Theatre at Munich. To this for six years he devoted his best efforts, presenting in the most admirable manner the finest of the German classics. The merit of his work was recognized by the king, who ennobled him in 1857. He was pre-eminently a theatrical manager, and served successively at Weimar (1857) and at Vienna, where he was appointed director of the Court Opera House in 1867, and of the Burg Theatre in 1870. He brought the classic plays of other lands upon the stage, and his revivals of Shakespeare's historical plays and the 'Winter's Tale,' and of Molière's 'L'Avare' (The Miser), were brilliant events in the theatrical annals of Vienna. He was made Imperial Councilor by the Emperor, and raised in 1876 to the rank of baron. In 1875 he took the position of general director of both court theatres of Vienna. He died at Vienna, May 15th, 1881.

The novels 'Licht und Schatten der Liebe' (The Light and Shadow of Love: 1838); 'Heptameron,' 1841; and 'Novellenbuch,' 1855, were not wholly successful; but in contrast to these, 'Unter der Erde' (Under the Earth: 1840); 'Sieben Friedliche Erzählungen' (Seven Peaceful Tales: 1844), and 'Die Amazone' (The Amazon: 1868), are admirable.

Regarded purely as literature, Dingelstedt's best productions are his early poems, although his commentaries upon Shakespeare and Goethe are wholly praiseworthy. He was successful chiefly as a political poet, but his muse sings also the joys of domestic life. 'Hauslieder' (Household Songs: 1844), and his poems upon Chamisso and Uhland, are among the most beautiful personal poems in German literature.

A MAN OF BUSINESS

From 'The Amazon': copyrighted by G.P. Putnam's Sons

Herr Krafft was about to reply, but was prevented by the hasty appearance of Herr Heyboldt, the first procurist, who entered the apartment; not an antiquated comedy figure in shoe-buckles, coarse woolen socks, velvet pantaloons, and a long-tailed coat, his vest full of tobacco, and a goose-quill back of his comically flexible ear; no, but a fine-looking man, dressed in the latest style and in black, with a medal in his button-hole, and having an earnest, expressive countenance. He was house-holder, member of the City Council, and militia captain; the gold medal and colored ribbon on his left breast told of his having saved, at the risk of his own life, a Leander who had been carried away by the current in the swimming-baths.

His announcement, urgent as it was, was made without haste, deliberate and cool, somewhat as the mate informs the captain that an ugly wind has sprung up. "Herr Principal," he said, "the crowd has broken in the barriers and one wing of the gateway; they are attacking the counting-house." "Who breaks, pays," said Krafft, with a joke; "we will charge the sport to their account."—"The police are not strong enough; they have sent to the Royal Watch for military."—"That is right, Heyboldt. No accident, no arms or legs broken?"—"Not that I know of."—"Pity for Meyer Hirsch; he would have thundered magnificently in the official Morning News against the excesses of the rage for speculation. Nor any one wounded by the police?"—"Not any, so far."—"Pity for Hirsch Meyer. The oppositional Evening Journal has missed a capital opportunity of weeping over the barbarity of the soldateska. At all events, the two papers must continue to write—one for, the other against us. Keep Hirsch Meyer and Meyer Hirsch going."—"All right, Herr Principal."—"Send each of them a polite line, to the effect that we have taken the liberty of keeping a few shares for him, to sell them at the most favorable moment, and pay him over the difference."—"It shall be attended to, Herr Principal."—"So our Southwestern Railway goes well, Heyboldt?"—"By steam, Herr Principal." The sober man smiled at his daring joke, and Herr Krafft smiled affably with him. "The amount that we have left to furnish will be exhausted before one has time to turn around. The people throw money, bank-notes, government bonds, at our cashiers, who cannot fill up the receipts fast enough. On the Bourse they fought for the blanks."—"For the next four weeks we will run the stock up, Heyboldt; after that it can fall, but slowly, with decorum."—"I understand, Herr Principal."

A cashier came rushing in without knocking. "Herr Principal," he stammered in his panic, "we have not another blank, and the people are pouring in upon us more and more violently. Wild shouts call for you." "To your place, sir," thundered Krafft at him. "I shall come when I think it time. In no case," he added more quietly, "before the military arrive. We need an interference, for the sake of the market." The messenger disappeared; but pale, bewildered countenances were to be seen in the doorways of the comptoir; the house called for its master: the trembling daughter sent again and again for her father.

"Let us bring the play to a close," said Herr Krafft, after brief deliberation; he stepped into the middle office, flung open a window, and raising his harsh voice to its loudest tones, cried to the throng below, "You are looking for me, folks. Here I am. What do you want of me?" "Shares, subscriptions," was the noisy answer.—"You claim without any right or any manners. This is my house, a peaceable citizen's house. You are breaking in as though it were a dungeon, an arsenal, a tax-office,—as though we were in the midst of a revolution. Are you not ashamed of yourselves?" A confused murmur rang through the astonished ranks. "If you wish to do business with me," continued the merchant, "you must first learn manners and discipline. Have I invited your visit? Do I need your money, or do you need my shares? Send up some deputies to convey your requests. I shall have nothing to do with a turbulent mob." So saying, he closed the window with such violence that the panes cracked, and the fragments fell down on the heads of the assailants.

"The Principal knows how to talk to the people," said Heyboldt with pride to Roland, the mute witness of this strange scene. "He speaks their own language. He replies to a broken door with a broken window."

Meantime a company of soldiers had arrived on double-quick, with a flourish of drums. The officer's word of command rang through the crowd, now grown suddenly quiet: "Fix bayonets! form line! march!" Yard and passages were cleared, the doors guarded; in the street the low muttering tide, forced back, made a sort of dam. Three deputies, abashed and confused, appeared at Krafft's door and craved audience. The merchant received them like a prince surrounded by his court, in the midst of his clerks, in the large counting-room. The spokesman commenced: "We ask your pardon, Herr Krafft, for what has happened."—"For shame, that you should drag in soldiers as witnesses and peacemakers in a quiet little business affair among order-loving citizens."—"It was reported that we had been fooled with these subscriptions, and that the entire sum had been already disposed of on the Bourse."—"And even if that were so, am I to be blamed for it? The Southwestern Railway must raise thirty millions. Double, treble that amount is offered it. Can I prevent the necessity of reducing the subscriptions?"—"No; but they say that we poor folks shall not get a cent's worth; the big men of the Bourse have gobbled up the best bits right before our noses."—"They say so? Who says so? Court Cooper Täubert, I ask you who says so?"—"Gracious Herr Court Banker—" "Don't Court or Gracious me. My name is Krafft, Herr Hans Heinrich Krafft. I think we know each other, Master Täubert. It is not the first time that we have done business together. You have a very snug little share in my workingmen's bank. Grain-broker Wüst, you have bought one of the houses in my street. Do I ever dun you for the installments of purchase money?" "No indeed, Herr Krafft; you are a good man, a public-spirited man, no money-maker, no leech, no Jew!" cried the triumvirate of deputies in chorus.—"I am nothing more than you are: a man of business, who works for his living, the son of a peasant, a plain simple citizen. I began in a smaller way than any of you; but I shall never forget that I am flesh of your flesh, blood of your blood. Facts have proved it. I will give you a fresh proof to-day. Go home and tell the people who have sent you, Hans Heinrich Krafft will give up the share which his house has subscribed to the Southwestern Railway, in favor of the less wealthy citizens of this city. This sum of five hundred thousand thalers shall be divided up pro rata among the subscriptions under five hundred dollars."

"Heaven bless you, Herr Krafft!" stammered out the court cooper, and the grain-broker essayed to shed a tear of gratitude; the confidential clerk Herr Lange, the third of the group, caught at the hand of the patron to kiss it, with emotion. Krafft drew it back angrily. "No self-abasement, Herr Lange," he said. "We are men of the people; let us behave as such. God bless you, gentlemen. You know my purpose. Make it known to the good people waiting outside, and see that I am rid of my billeting. Let the subscriptions be conducted quietly and in good order. Adieu, children!" The deputation withdrew. A few minutes afterwards there was heard a thundering hurrah:—"Hurrah for Herr Krafft! Three cheers for Father Krafft!" He showed himself at the window, nodded quickly and soberly, and motioned to them to disperse.

While the tumult was subsiding, Krafft and Roland retired into the private counting-room. "You have," the latter said, "spoken nobly, acted nobly."—"I have made a bargain, nothing more, nothing less; moreover, not a bad one."—"How so?"—"In three months I shall buy at 70, perhaps still lower, what I am now to give up to them at 90."—"You know that beforehand?"—"With mathematical certainty. The public expects an El Dorado in the Southwestern Railway, as it does in every new enterprise. The undertaking is a good one, it is true, or I should not have ventured upon it. But one must be able to wait until the fruit is ripe. The small holders cannot do that; they sow today, and tomorrow they wish to reap. At the first payment their heart and their purse are all right. At the second or third, both are gone. Upon the least rise they will throw the paper, for which they were ready to break each other's necks, upon the market, and so depreciate their property. But if some fortuitous circumstance should cause a pressure upon the money market, then they drop all that they have, in a perfect panic, for any price. I shall watch this moment, and buy. In a year or so, when the road is finished and its communications complete, the shares that were subscribed for at 90, and which I shall have bought at 60 to 70, will touch 100, or higher."

"That is to say," said Roland, thoughtfully, "you will gain at the expense of those people whose confidence you have aroused, then satisfied with objects of artificial value, and finally drained for yourself." "Business is business," replied the familiar harsh voice. "Unless I become a counterfeiter or a forger I can do nothing more than to convert other persons' money into my own; of course, in an honest way."—"And you do this, without fearing lest one day some one mightier and luckier than you should do the same to you?"—"I must be prepared for that; I am prepared."—"Also for the storm,—not one of your own creating, but one sent by the wrath of God, that shall scatter all this paper splendor of our times, and reduce this appalling social inequality of ours to a universal zero?" "Let us quietly abide this Last Day," laughed the banker, taking the artist by the arm.

THE WATCHMAN

The last faint twinkle now goes out Up in the poet's attic; And the roisterers, in merry rout, Speed home with steps erratic.

Soft from the house-roofs showers the snow, The vane creaks on the steeple, The lanterns wag and glimmer low In the storm by the hurrying people.

The houses all stand black and still, The churches and taverns deserted, And a body may now wend at his will, With his own fancies diverted.

Not a squinting eye now looks this way, Not a slanderous mouth is dissembling, And a heart that has slept the livelong day May now love and hope with trembling.

Dear Night! thou foe to each base end, While the good still a blessing prove thee, They say that thou art no man's friend,— Sweet Night! how I therefore love thee!

DIOGENES LAERTIUS

(200-250 A. D.?)

t is curious how often we are dependent, for our knowledge of some larger subject, upon a single ancient author, who would be hardly worthy of notice but for the accidental loss of the books composed by fitter and abler men. Thus, our only general description of Greece at the close of the classical period is written by a man who describes many objects that he certainly did not see, who leaves unmentioned numberless things we wish explained, and who has a genius for so misplacing an adverb as to bring confusion into the most commonplace statement. But not even to Pausanias do we proffer such grudging gratitude and such ungrateful objurgations as to Diogenes Laertius, our chief—often our sole—authority for the 'Lives and Sayings of the Philosophers.' His book is a fascinating one, and even amusing, if we can forget what we so much wanted in its stead. At second or third hand, from the compendiums of the schools rather than from the original works of the great masters themselves, Diogenes does give us a fairly intelligible sketch, as a rule, of the outward life lived by each sage. This slight frame is crammed with anecdotes, evidently culled with most eager and uncritical hand from miscellaneous collections. Many of these stories are so fragmentary as to be pointless. Others are unquestionably attached to the wrong person. This method is at its maddest in the author's sketch of his namesake, the Recluse of the Tub. (One of Ali Baba's jars, by the way, would give a better notion of the real hermitage.) Since this "philosopher" had himself little character and no doctrines, the loose string of anecdotes, puns, and saucy answers suits all our needs. Throughout the work are scattered, apocryphal letters, and feeble poetic epigrams composed by the compiler himself. The leaning of our most unphilosophic author was apparently toward Epicurus. The loss of that teacher's own works causes us to prize doubly the extensive fragments of them preserved in this relatively copious and serious study. The lover of the great Epicurean poem of Lucretius on the 'Nature of Things' will often be surprised to find here the source of many among the Roman poet's most striking doctrines and images. The sketch of Zeno is also an important authority on Stoicism. Instruction in these particular chapters, then, and rich diversion elsewhere, await the reader of this most gossipy, formless, and uncritical volume. The English reader, by the way, ought to be provided with something better than the "Bohn" version. This adds a goodly harvest of ludicrous misprints and other errors of every kind to Diogenes's own mixture of borrowed wisdom and native silliness. The classical student will prefer the Didot edition by Cobet, with the Latin version in parallel columns.

It has been thought desirable to offer here a version, slightly abridged, of Diogenes's chapter on Socrates. The original sources, in Plato's and Xenophon's extant works, will almost always explain, or correct, the statements of Diogenes. Such wild shots as the assertion that the plague repeatedly visited Athens, striking down every inhabitant save the temperate Socrates, hardly need a serious rejoinder. Diogenes cannot even speak with approximate accuracy of Socrates's famous Dæmon or Inward Monitor. We know, on the best authority, that it prophesied nothing, even proposed nothing, but only vetoed the rasher impulses of its human companion. But to apply the tests of mere accuracy to Diogenes would be like criticizing Uncle Remus for his sins against English syntax.

Of the author's life we know nothing. Our assignment of him to the third century is based merely on the fact that he quotes writers of the second, and is himself in turn cited by somewhat later authors.

LIFE OF SOCRATES

From the 'Lives and Sayings of the Philosophers'

Socrates was the son of Sophroniscus a sculptor and Phænarete a midwife [as Plato also states in the 'Theaetetus'], and an Athenian, of the deme Alopeke. He was believed to aid Euripides in composing his dramas. Hence Mnesimachus speaks thus:—

"This is Euripides's new play, the 'Phrygians': And Socrates has furnished him the sticks."

And again:—

"Euripides, Socratically patched."

Callias also, in his 'Captives,' says:—

A—"Why art so solemn, putting on such airs? B—Indeed I may; the cause is Socrates."

Aristophanes, in the 'Clouds,' again, remarks:—

"And this is he who for Euripides Composed the talkative wise tragedies."

He was a pupil of Anaxagoras, according to some authorities, but also of Damon, as Alexander states in his 'Successions.' After the former's condemnation he became a disciple of Archelaus the natural philosopher. But Douris says he was a slave, and carried stones. Some say, too, that the Graces on the Acropolis are his; they are clothed figures. Hence, they say, Timon in his 'Silli' declares:—

"From them proceeded the stone-polisher, Prater on law, enchanter of the Greeks, Who taught the art of subtle argument, The nose-in-air, mocker of orators, Half Attic, the adept in irony."

For he was also clever in discussion. But the Thirty Tyrants, as Xenophon tells us, forbade him to teach the art of arguing. Aristophanes also brings him on in comedy, making the Worse Argument seem the better. He was moreover the first, with his pupil Æschines, to teach oratory. He was likewise the first who conversed about life, and the first of the philosophers who came to his end by being condemned to death. We are also told that he lent out money. At least, investing it, he would collect what was due, and then after spending it invest again. But Demetrius the Byzantine says it was Crito who, struck by the charm of his character, took him out of the workshop and educated him.

Realizing that natural philosophy was of no interest to men, it is said, he discussed ethics, in the workshops and in the agora, and used to say he was seeking

"Whatsoever is good in human dwellings, or evil."

And very often, we are told, when in these discussions he conversed too violently, he was beaten or had his hair pulled out, and was usually laughed to scorn. So once when he was kicked, and bore it patiently, some one expressed surprise; but he said, "If an ass had kicked me, would I bring an action against him?"

Foreign travel he did not require, as most men do, except when he had to serve in the army. At other times, remaining in Athens, he disputed in argumentative fashion with those who conversed with him, not so as to deprive them of their belief, but to strive for the ascertainment of truth. They say Euripides gave him the work of Heraclitus, and asked him, "What do you think of it?" And he said, "What I understood is fine; I suppose what I did not understand is, too; only it needs a Delian diver!" He attended also to physical training, and was in excellent condition. Moreover, he went on the expedition to Amphipolis, and when Xenophon had fallen from his horse in the battle of Delium he picked him up and saved him. Indeed, when all the other Athenians were fleeing he retreated slowly, turning about calmly, and on the lookout to defend himself if attacked. He also joined the expedition to Potidæa—by sea, for the war prevented a march by land; and it was there he was said once to have remained standing in one position all night. There too, it is said, he was pre-eminent in valor, but gave up the prize to Alcibiades, of whom he is stated to have been very fond. Ion of Chios says moreover that when young he visited Samos with Archelaus, and Aristotle states that he went to Delphi. Favorinus again, in the first book of his 'Commentaries' says he went to the Isthmus.

He was also very firm in his convictions and devoted to the democracy, as was evident from his not yielding to Critias and his associates when they bade him bring Leon of Salamis, a wealthy man, to them to be put to death. He was also the only one who opposed the condemnation of the ten generals. When he could have escaped from prison, too, he would not. The friends who wept at his fate he reproved, and while in prison he composed those beautiful discourses.

He was also temperate and austere. Once, as Pamphila tells us in the seventh book of her 'Commentaries,' Alcibiades offered him a great estate, on which to build a house; and he said, "If I needed sandals, and you offered me a hide from which to make them for myself, I should be laughed at if I took it." Often, too, beholding the multitude of things for sale, he would say to himself, "How many things I do not need!" He used constantly to repeat aloud these iambic verses:—

"But silver plate and garb of purple dye To actors are of use,—but not in life."

He disdained the tyrants,—Archelaus of Macedon, Scopas of Crannon, Eurylochus of Melissa,—not accepting gifts from them nor visiting them. He was so regular in his way of living that he was frequently the only one not ill when Athens was attacked by the plague.

Aristotle says he wedded two wives, the first Xanthippe, who bore him Lamprocles, and the second Myrto, daughter of Aristides the Just, whom he received without dowry and by whom he had Sophroniscus and Menexenus. Some however say he married Myrto first; and some again that he had them both at once, as the Athenians on account of scarcity of men passed a law to increase the population, permitting any one to marry one Athenian woman and have children by another; so Socrates did this.

He was a man also able to disdain those who mocked him. He prided himself on his simple manner of living, and never exacted any pay. He used to say he who ate with best appetite had least need of delicacies, and he who drank with best appetite had least need to seek a draught not at hand; and that he who had fewest needs was nearest the gods. This indeed we may learn from the comic poets, who in their very ridicule covertly praise him. Thus Aristophanes says:—

"O thou who hast righteously set thy heart on attaining to noble wisdom, How happy the life thou wilt lead among the Athenians and the Hellenes! Shrewdness and memory both are thine, and energy unwearied Of mind; and never art thou tired from standing or from walking. By cold thou art not vexed at all, nor dost thou long for breakfast. Wine thou dost shun, and gluttony, and every other folly."

Ameipsias also, bringing him upon the stage in the philosopher's cloak, says:—

"O Socrates, best among few men, most foolish of many, thou also Art come unto us; thou'rt a patient soul; but where didst get that doublet? That wretched thing in mockery was presented by the cobblers! Yet though so hungry, he never however has stooped to flatter a mortal."

This disdain and arrogance in Socrates has also been exposed by Aristophanes, who says:—